c/o The Historical Observer

Content warning: Violence, death

Shakespeare wrote, “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” That’s because he hadn’t met Joseph Hough, a man in his 30s whose affections weren’t scorned so much as unreciprocated by 19-year-old May Smith. His solution? Commit the gristly murder of 23-year-old Harry Chadwick, her fiancé.

The year was 1899. Chadwick rode his bicycle from New Britain to Chester as he did every Sunday to visit the subject of his affection, May Smith. As the sun eased its way through the sky, he decided to stop for a rest and a bite to eat in Middletown. Little did he know that it would be his last meal.

Early the next morning, a resident discovered a slowly coagulating pool of blood on the road outside his door in Tylerville. A trail of smeared blood led toward Clark Creek, an offshoot of the Connecticut River. Serenely floating in the creek was a rowboat, patiently coloring the water around it red. It was completely empty except for one broken oar, covered in hair and blood. Another bloody path led, like a gory bread crumb trail, towards Chester and May.

Aiden, May Smith’s brother, rose early that morning to find Hough, who was a carpenter boarding with the family, moaning in his bed and almost unconscious. The white sheets near his head were soaked with blood and he had a three inch slash across his neck.

Immediately speculation began to fly, though Hough maintained his innocence, saying that Chadwick’s murder had been self-defense.

“I went to…scare Chadwick…he came to me…We had a scuffle for some time…He cut me…I shouted for help.” read Hough’s coroner statement, printed in the Penny Press Newspaper, a now-defunct newspaper based in Middletown. “I…caught him by the throat and held on. I did not intend to hurt him, but I got desperate and kept holding on.”

Discovering in horror what he had done, Hough dragged the body towards the creek to dispose of the body. He found a boat but needed something to stop the body from floating to the surface. The answer came in a flash: the bicycle.

“I then tied the bicycle to the body and rowed the boat down the creek to the [Connecticut] river…and threw the body overboard.”

Chadwick’s bicycle would disappear with him, like he had never come through Middletown at all.

Soon, however Hough was imprisoned. It came out that he had served time in a state reform school as a child and had a family history of insanity. The public began to reject his story of self defense.

This brings us to December, five months after the murder. The imposing towers of the Middletown county courthouse cast long shadows over the jury as they filed into the building. The windows seemed to peer accusingly down upon Hough as he entered, followed by Smith and her family. Throughout the day, Hough adamantly pleaded his innocence. However, the body of Chadwick, which had been dragged from the muddy depths of the river was damning evidence. He had been killed by a blow to the head with a blunt instrument.

“Chadwick had been terribly beaten about the head and face, either with a stone or an oar…possibly…both,” wrote the Penny Press. “The skull was broken in on one side so that the brain was exposed. The face was crushed and one arm broken.”

When Smith bravely took the stand, testifying that Hough had frightened and sometimes stalked her, Hough still insisted that she had encouraged his attention. Bit by bit the prosecution chipped away at the sympathy of the jury.

“[A] nervous feeling of dread …seemed to pervade the courtroom…” the Penny Press wrote. “[Hough] sat with his eyes glued to the door that concealed the arbiters of his fate from his searching gaze…His attitude…was one of deep dejection.”

An excruciating four and a half hours passed where the crowd watched Hough count the minutes leading towards a decision that would irrevocably change his life. Like a solemn procession of funeral mourners, the 12 jury men funneled back into the courtroom. As the foreman rose the only sound was the crisp unfolding of a small piece of paper, containing one word he had already memorized. May Smith, Joseph Hough, prosecutor and defendant alike all drew a collective breath.

“We find Joseph Hough guilty of murder in the second degree.”

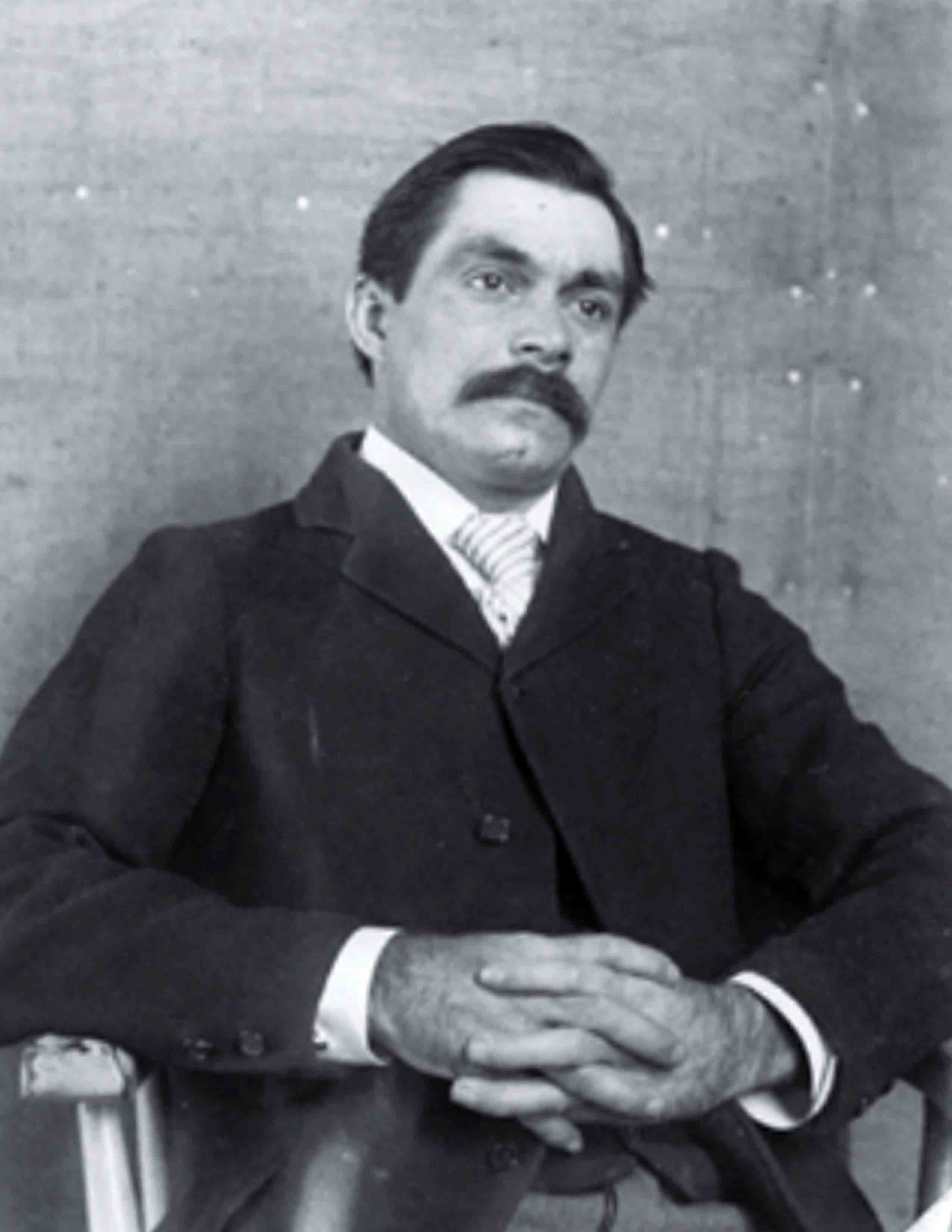

The words rippled back through the rows of watching public. He was sentenced to life in state prison. In his Haddam jail photograph, he is depicted casually leaning back in his chair with his hands casually folded and sporting a striped tie, a fairly festive choice for the occasion.

May Smith was publicly humiliated and hounded by gossip and blame; people accused her of leading Hough on. This, compounded with her consuming grief at the loss of her fiancé, forced her to move to Philadelphia, where she remained unmarried.

“After Harry [Chadwick] had spent the evening with May Smith, the girl that we both loved, he and I met,” Hough said in a statement to the New York Journal and Advertiser printed on July 18, 1899. “I reproached him for something that he said, for something that he did. He attacked me with a razor. I choked him. That’s all.”

Certain citizens, morbidly fascinated by the murder, sneaked down to the river at night and painstakingly carved off pieces of the bloody rowboat. These served as souvenirs from a time when they were so close to that dark side of humanity that they could have reached out and taken its hand.

Katerina Grealish can be reached at kgrealish@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed