From the Argives: Why The Campus Trolley Stopped

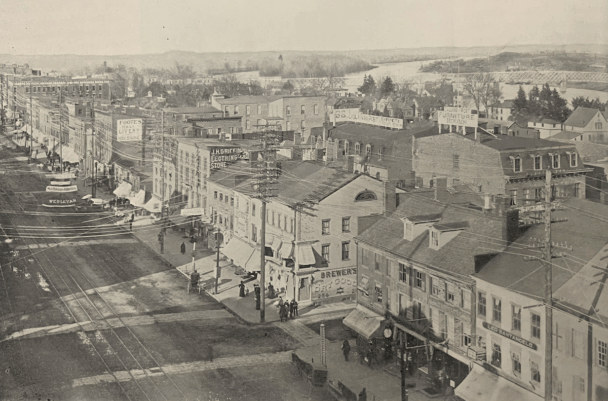

How many trolleys have you seen on campus? One hundred years ago, the rumble and rattle of sunflower-yellow streetcars was impossible to miss. These cars circled about Middletown at state-of-the-art speed on steel tracks that outlined the city. At the heart of this system stood the red-brick Middletown Street Railway Car-Barn (now home to Perkatory Coffee Roasters) that connected the local trolley line to an interurban railroad. Given the former scale of Middletown’s transportation network, it is no surprise that the Argives are full of its stories. Picking up at the dawn of the 20th century, we’re bringing last week’s trolley history into the station: first stop, Foss Hill.

1904: Wesleyan Gets Wired In

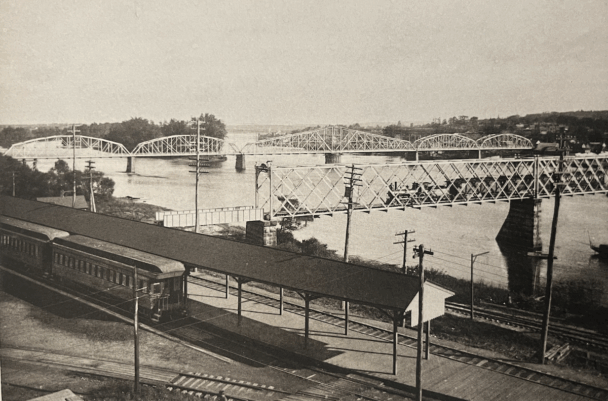

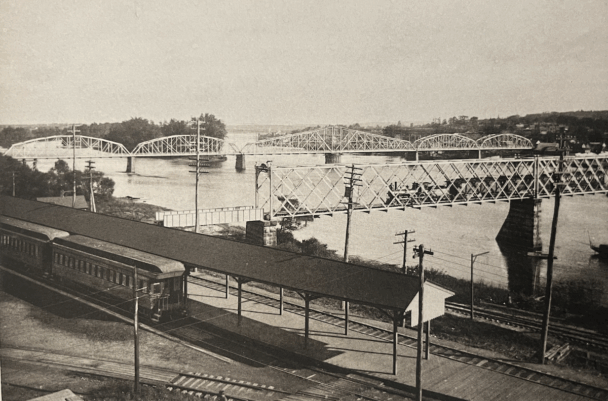

In 1904, a trolley line finally extended up from Main Street to several stops on Wesleyan’s campus. The tracks followed Mt. Vernon Street as it traversed the base of Foss Hill (before the street’s removal in 1956) and terminated at the junction of Pine Street and Miles Avenue. Now, a passenger arriving from a distant city by railroad could board a trolley at the train depot and, in a matter of minutes, arrive at Clark Hall.

Despite the expansions, the Middletown Street Railway Company remained unprofitable. Thus, in the same year, the Connecticut Company bought it in the process of consolidating local trolley lines into a statewide system. The Connecticut Company then merged its acquired trolley lines into a giant statewide trolley network that was then connected to other companies’ own trolley networks. The result: a passenger could board a streetcar on Main Street in Middletown and ride it as far south as New York City and as far north as Vermont.

1905 to 1926: Campus Athletics and Cannon Antics

Back when the Cardinals were the Methodists (Wesleyan’s mascot prior to 1932), sports teams used the trolley as their main form of transportation to away games. A sidebar in The Argus published Jan. 10, 1906, reports that the football team spent a whopping $596.87 on railroad and trolley costs during the 1905–06 academic year, equivalent to $21,485.83 today.

Wesleyan students also used trolleys to attend away games. On Jan. 7, 1926, The Argus posted a notice: “A special trolley has been chartered for the Trinity basketball game next Tuesday.” All traveling teams relied on this system, zipping across Connecticut alongside their loyal fans. In 1926, the total cost of the two-way trip to Hartford was 85 cents, equivalent to less than $16.00 today. The Methodists went on to beat Trinity that night, 43–10, and celebrate on the snowy ride home.

Students were often involved in more mischievous matters with the trolley. To these pranksters, the Douglas Cannon scrap was the perfect opportunity. Starting in 1859, Wesleyan first-years woke up early on George Washington’s birthday to fire sunrise cannon volleys from the Douglas Cannon. The annual cannon scrap took off in 1867, when “sophomores repeatedly attempted to foil the frosh efforts to fire the cannon,” according to Wesleyan’s Douglas Cannon blog. This ignited an interclass rivalry that grew “more elaborate, and dangerous, with each passing year.”

By 1907, the cannon competition had evolved into a full-scale tactical operation, according to The Argus’ enthusiastic report of that unforgettable night. “On the 27th of December, during the Christmas vacation, the freshmen had the cannon shipped from the Douglas factory to Highland, N. Y.,” The Argus explained. “About the first of February, it was reshipped to New Britain where it was enclosed in a sharp pointed, wooden box.”

However, the first-years weren’t content to just roll up with the cannon. They had planned for too long to undergo a proper match, and what’s a cannon scrap without a spectacle? “Two ‘fakes’ were also built…identical with the real cannon in regard to shape, size and weight,” wrote The Argus. The students stashed one fake by Pameacha Pond and stored the other fake in a barn in Portland, on the other side of the river.

The night of Feb. 21, cannon scrap eve, “a special freight trolley car brought the cannon and the…fake across the river.” The first-years deposited this fake cannon at the corner of Cross and Mt. Vernon. Then “the [trolley] car was run back,” picked up the fake cannon from Pameacha pond, and dropped it off at Wyllys Ave. A flock of first-years who had been hiding with the Douglas Cannon in the barn “had come over on the [trolley] car” to push the two fake cannons to campus. However, after hours of struggle and a handful of crowd crush injuries, the “1909 was victorious over 1910,” albeit “by a very small margin.”

The complexity of the 1907 cannon scrap proves the reach, efficiency, and reliability of the trolley system. Today’s XtraMile may hesitate to transport a gang of first-year students and three functioning cannons.

On March 14, 1921, The Argus published “The Red Hats Pass: Freshmen Doff Distinctive Headgear and Don Soph Pajamas for Evening,” a report on a ritualistic first-year revolt. (For context, Wesleyan has a long history of traditions meant to explicitly distinguish class years. For decades, first-year students were mandated to wear red hats at all times on campus grounds.) One night, when the sophomores were off “banqueting in Hartford,” the red-hatted first-years decided enough was enough and made for Andrus Field. “[The] freshmen, dressed in sophomores’ pajamas, solemnly laid their red hats upon an altar of burning barrels,” The Argus wrote. The stolen pajama–clad class snaked down to Main Street in “a long, impressive, white line, looming ghost-like in the flaring light” of the flaming hats.

Now on Main Street, the real antics began. Although the first-years were “abashed by the cold welcome” of the Middletown residents, they promptly “proceeded to adorn the Main Street by hanging their sleeping apparel on the trolley wires,” according to The Argus. “With interest and enthusiasm, and occasionally the addition of a finishing touch, the frosh viewed the effects of their innocent diversion upon passing trolley cars.” The sophomores did not comment.

As for the trolley wires themselves, they proved to be too great a temptation for other groups of Wesleyan students looking to play pranks on the town. “Years ago, the great outdoor sport was unhooking trolley wires,” recalled one unnamed resident in an interview with The Argus. “The students would come downtown in a big group and proceed to strew the sidewalks with trolley wires. Just how they got them down without being electrocuted is a question, but they never seemed to have much trouble.”

1927 to 1937: The End of the Line

This unnamed resident was the focus of “Old Resident of Middletown Finds Rioters Less Exuberant Than He-Men of Yore,” an article published in The Argus on Feb. 16, 1933. The resident’s memories of Wesleyan line up with the end of America’s freight frenzy in the 1930s.

“Nope, there ain’t been much happenin’ these days,” the resident observed. “The old college’s been pretty quiet.”

An alternative to the trolley arrived: the bus. Because buses did not require the infrastructure of tracks, electric wires, and a trolley barn, they were much cheaper to operate, and therefore preferable to executives in a floundering industry.

Public transportation companies across the nation began to replace streetcars with buses. Now, instead of chartering trolleys, Wesleyan students took buses to away games. On Oct. 27. 1932, The Argus printed a notice that read, “If enough men wish to go to the Williams game a bus will be chartered for the trip. The round trip fare will be $2.75,” nearly $65.00 in today’s money. “It is hoped that sufficient support will be given by undergraduates to make possible the sending of several busses to the game,” the article states. There was no longer a trolley for Wesleyan to lean on.

Though buses were cheaper to run, Wesleyan students did not always see these savings. On Oct. 25, 1923, The Argus advertised two-way bus tickets to an upcoming game at Amherst. Tickets cost $5.00 each, equivalent to $91.86 today. According to The Argus, the Amherst trip would use “the standard yellow auto busses that the Connecticut Company uses on its passenger lines.” The same Connecticut Company that built Middletown’s trolley now filled its streets with bus passenger lines.

The Connecticut Company’s parent corporation, the New Haven Railroad, saw its finances decline during the 1930s, ultimately facing bankruptcy in 1935. The decline in popularity of the trolleys and the better operational economics of buses must have also impacted the Connecticut Company’s decision to ultimately cease operations of the trolley system in Middletown during the 1930s. Trolleys had become a part of the past.

1938 to 2000: Drifting into the Car Century

The Arrigoni Bridge opened in Middletown in 1938, replacing the Old Iron Bridge as a connection between Middletown and Portland. Unlike its predecessor, the Arrigoni Bridge contained no trolley lines, but four lanes of roadway. Buses had won for now. With car culture on the rise and bus programs stripped of funding, the world of public transport hung in the balance.

As Middletown and Wesleyan settled into the new nationwide norm, The Argus had little to say of railways, trolleys, or buses. C.W. Snow Jr. ’47 authored the paper’s next public transport survey in 1943, titled “Suggestions to Naval Cadets.” Snow’s article catered to the Naval cadets—stationed at Wesleyan’s V-5 and V-12 Naval Training Units on campus during World War II—looking for the best ways to spend the weekend around Middletown.

“The Legion Hall in Cromwell, where the dances are held, is situated approximately two miles north of Middletown on the road to Hartford” Snow suggested. “I think that you will find the ‘bumming’ very good, but if you run into hard luck there is always the Hartford bus which runs ‘on the hour.’” Streets full of automobiles made hitchhiking, what Snow calls “bumming,” possible.

The network effects of public transportation systems make them difficult to erase entirely. “[Hartford] is easily accessible by bus,” Snow wrote, outlining a system of buses that allowed one to travel from Middletown to Meriden, Waterbury, or New Haven.

2007 to Present: Concepts of a Plan

In recent years, the idea of constructing a new trolley system in Middletown has resurfaced. On Oct. 31, 2008, an Argus article by Katherine Yagle ’12 reported that the Middletown City Council was considering putting down money to put up new trolley lines on Main Street. “Funded by federal grants, the plan is part of an $18 million project to study and improve parking and transportation downtown,” Yagle wrote.

The final report of the city’s plans, titled “Parking and Traffic Study for the Central Business District,” envisioned a “tracked, steel-wheeled streetcar operating on the inside travel lane of each side of Main Street.” Despite the potential benefit of decreased congestion, the report predicted a streetcar system would cost “$7.6 million per track mile and [have] annual operating costs of $600,000 per year.”

In 2013, Middletown resident Jonathan Willetts sent a public letter to the Middletown Director of the Department of Planning, Conservation, and Development, making the economic case for the trolley’s return. “In city after city across America, light-rail systems are making a dramatic comeback,” Willetts wrote. “Initially reluctant in some cases…once people began using the light-rail systems, they quickly accepted them and did not simply love them, they couldn’t get enough of them!”

Willetts acknowledged the high costs of putting up the long-lasting infrastructure of a trolley line. “Expensive? Yes, but it will never be less expensive than right now,” he wrote. “Would future value justify the initial outlay? You betcha! In spades!”

Hope Cognata can be reached at hcognata@wesleyan.edu.

Nathan Yamamoto can be reached at nyamamoto@wesleyan.edu.

“From the Argives” is a column that explores The Argus’ archives (Argives) and any interesting, topical, poignant, or comical stories that have been published in the past. Given The Argus’ long history on campus and the ever-shifting viewpoints of its student body, the material, subject matter, and perspectives expressed in the archived article may be insensitive or outdated, and do not reflect the views of any current member of The Argus. If you have any questions about the original article or its publication, please contact Head Archivists Hope Cognata at hcognata@wesleyan.edu and Lara Anlar at lanlar@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply