c/o Wesleyan University

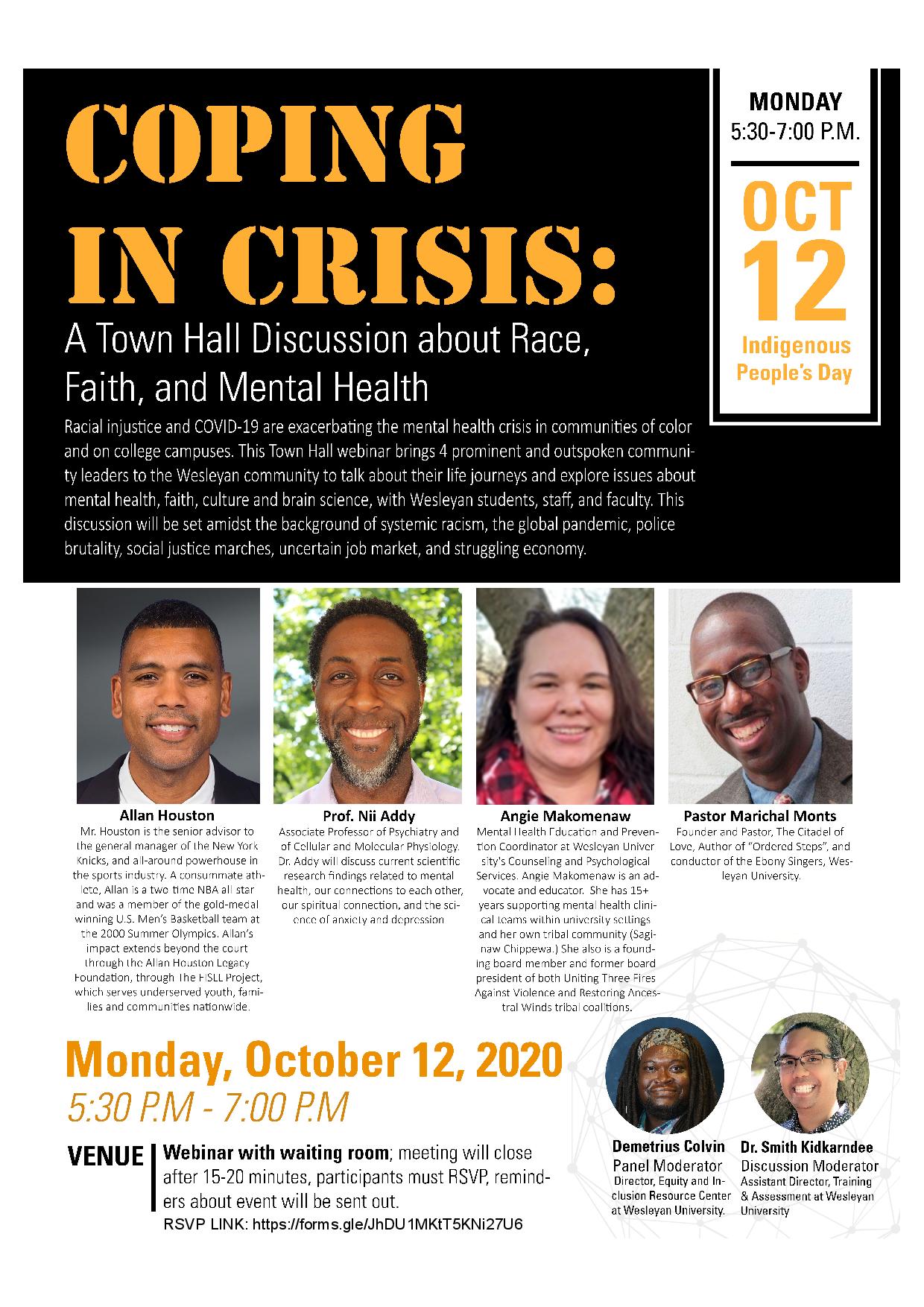

A town hall event entitled “Coping in Crisis” was held Monday, Oct. 12 via Zoom. Organized by Neuroscience and Behavior Professor Janice Naegele and Senior Class President Pablo Wickham ’21, the discussion focused on race, faith, and mental health. The event featured four panelists: former NBA athlete Allan Houston, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Yale University Nii Addy, Wesleyan Mental Health Education and Prevention Coordinator Angie Makomenaw, and Pastor and Ebony Singers Conductor Marichal Monts.

The town hall was moderated by Resource Center Director Demetrius Colvin and Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) Assistant Director of Training and Assessment Dr. Smith Kidkarndee. The event was attended by 409 faculty and students, as well as prospective students and families.

Colvin opened the town hall with a brief introduction about his work in the Resource Center and a land acknowledgement to the Wangunk tribe, the original residents of the land Wesleyan is built on. Then each panelist introduced themselves.

Houston, who played professional basketball for the Detroit Pistons and New York Knicks, discussed his organization, the Faith, Integrity, Sacrifice, Leadership, and Legacy Project (FISLL), which works with underserved youth across the United States. Houston then explained the significance of the values that constitute FISLL.

“When we look at these five values of faith, integrity, sacrifice, leadership, and legacy, this is what we really like to look at as the fundamentals of life,” Houston said. “They’re a foundation. And the one thing that we just like to understand and promote is that our legacy, what we want to become, who we want to become and our impact on the world around us has to be intentional.”

Afterwards, Addy, a second generation immigrant to the United States from Ghana explained how his work was influenced by his father’s interest in neuroscience, his faith as a Christian, and how his identity as a Black man impacts his perspective on the prevalence of racial justice in academics.

Makomenaw introduced herself, first in her native language, as a member of the Ojibwe tribe, later going on to discuss her experience in supporting survivors of gender violence through their process with the criminal justice system. Currently, Makomenaw is working as a new member of the CAPS team at the University.

Monts explained that he first became affiliated with the University in 1981 as a student and noted his time as a member of Ujamaa, Wesleyan’s Black Student Union. Monts explained that he felt the need to give back to his community of Hartford. Monts began to teach music, which led him to return to the University to begin teaching Ebony Singers in 1986, a class that meets weekly to sing gospel music in Memorial Chapel. Monts is also a Pastor at the Citadel of Love in the North End of Hartford.

“I’ve come to find out through the years that I was placed there, my purpose there is to be part of the spiritual skyline of Middletown, to be able to help young people who are trying to find their way in spirituality without being forceful,” Monts explained.

Lastly, Kidkarndee spoke about his work training CAPS clinicians in cultural competency, as well as ways to explore the intersections of race, sexuality, and gender as they relate to psychology. Kidkarndee is interested in the advancement of racial equity in mental health.

Next, Colvin asked the panelists to discuss the current state of conversations surrounding mental health in society, as well as strategies for maintaining a healthy mental state and work life balance in a time of uncertainty and violence.

Monts discussed the stigma that came with discussions about mental health in his family growing up.

“Certainly as a Black man, I remember being taught that I’m not allowed to cry, I’m not allowed to feel, you’re supposed to be strong,” Monts said. “My father died when I was 12 years old, and my grandmother walks up to me and says well, you gotta be the man of the house now. So at 12 years old I started trying to learn to be the man of the house, which is totally wrong, and now I know I shouldn’t have been doing that, but there’s stigma attached to it.”

Houston explained that in difficult times, his faith has consistently provided him with a pathway forward and a better sense of self.

“I think what happened is that—a teammate of mine invited me to go to Bible studies, and what that did for me was it helped me kind of negotiate and navigate, who am I outside of what I’m doing,” Houston said. “Who am I outside of this sport, or this gift, or this calling that impacts other people?”

Further elaborating on the role of faith in maintaining mental health, Addy explained the way that he approaches mental health from his dual positionality as a Professor of Psychiatry and a Christian.

“For me as a Christian, I don’t dismiss the power of God to work in people’s life and to bring healing, but that doesn’t mean that He hasn’t given us tools to be able to address that mental health,” Addy said. “So we can’t ignore psychological interventions, we can’t ignore the knowledge that we have about the brain, all these other components, all the aspects of race.”

Makomenaw added that in her indigenous community, dealing with the impact of COVID-19 means mutual care.

“I’ve been really struggling with the whole, just, not wearing a mask outside,” Makomenaw said. “Because for my community, that’s just a given, you take care of others, you do things to support others, and so wearing a mask is one of those simple ways that we can do it. In that aspect, if one part of your community is not healthy, that affects the entire community, and so therefore it’s not just what you’re going through as far as struggles, but as a community what is going on.”

Following this discussion on mental health, Colvin asked the panelists to speak about resilience and places in which they find strength, at which point Makomenaw took a moment to acknowledge her family, community, and the power that comes with survival.

“I have strong women in my family, and we’ve survived, pretty much, genocide in order to even have our existence now,” Makomenaw said. “Thinking of what we’ve gone through, and what my ancestors have gone through, acknowledging that we are still here—I find strength in that, in that existence, and my children, in just knowing it.”

After a few more minutes of discussion from the panelists, Kidkardnee answered questions from the audience, one of which asked about how people can cope when their work or social position entails great responsibility.

Monts explained that in his work as a pastor, he has had to learn to step away from helping others.

“If you don’t rest well, then you cannot give whatever you have or whoever you are, you cannot give your best self to people when you do show up,” Monts explained. “So you must. You are not doing anything wrong to take time for you.”

Another question from the audience asked the panelists to discuss coping mechanisms for those who are not part of a group rooted in religion or faith. Addy explained that, even on a neurological level, being in community is vital.

“Tying it back to even the brain, there’s a whole bunch of neuroscience evidence that shows the importance of us being in community,” Addy explained. “You can even see that when you’re studying things like rats and mice in the lab. When they’re in community together, when they have toys to play with, that changes their brains, that makes them more resilient. They’re less likely to get into patterns that we would associate with some of the same things that we as humans would struggle with, both depression and anxiety.”

After a few more questions and answers and final acknowledgements, Colvin thanked the various campus organizations that sponsored the town hall and transitioned to four Zoom breakout rooms for further reflection and conversation. Colvin, Addy, Makomenaw, University Jewish Chaplain and Director of Religious and Spiritual Life Rabbi David Leipziger Teva, Resource Center Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality Intern Jada Reid ’22, and Mindfulness Intern Tyla Taylor ’21 hosted the rooms.

Naegele said that she deeply appreciated that so many students attended the event, and hopes that the University will continue to host conversations that focus on wellness in conjunction with current events.

“That’s where I want this to go in the future,” Naegele said. “I want there to be more town halls or other venues where students feel safe talking about mental health issues they’re having, feelings of isolation, feelings of being overwhelmed.”

Wickham, who worked closely with Naegele in organizing the event and selecting panelists, said that alongside the importance of the discussions about race and mental health for people of color that the town hall centered, the collaboration involved made it special for him.

“A lot of times we try to do the work in silos and then the campus becomes over-programmed,” Wickham wrote in an email to The Argus. “But if we work together and normalize collaborating then our reach will be greater and more impactful. At the end of the day, it is not about who gets the credit but about what the work will go on to accomplish. I want this town hall to be an annual event and see it grow even more.”

Emma Smith can be reached at elsmith@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed