c/o wesleyan.edu

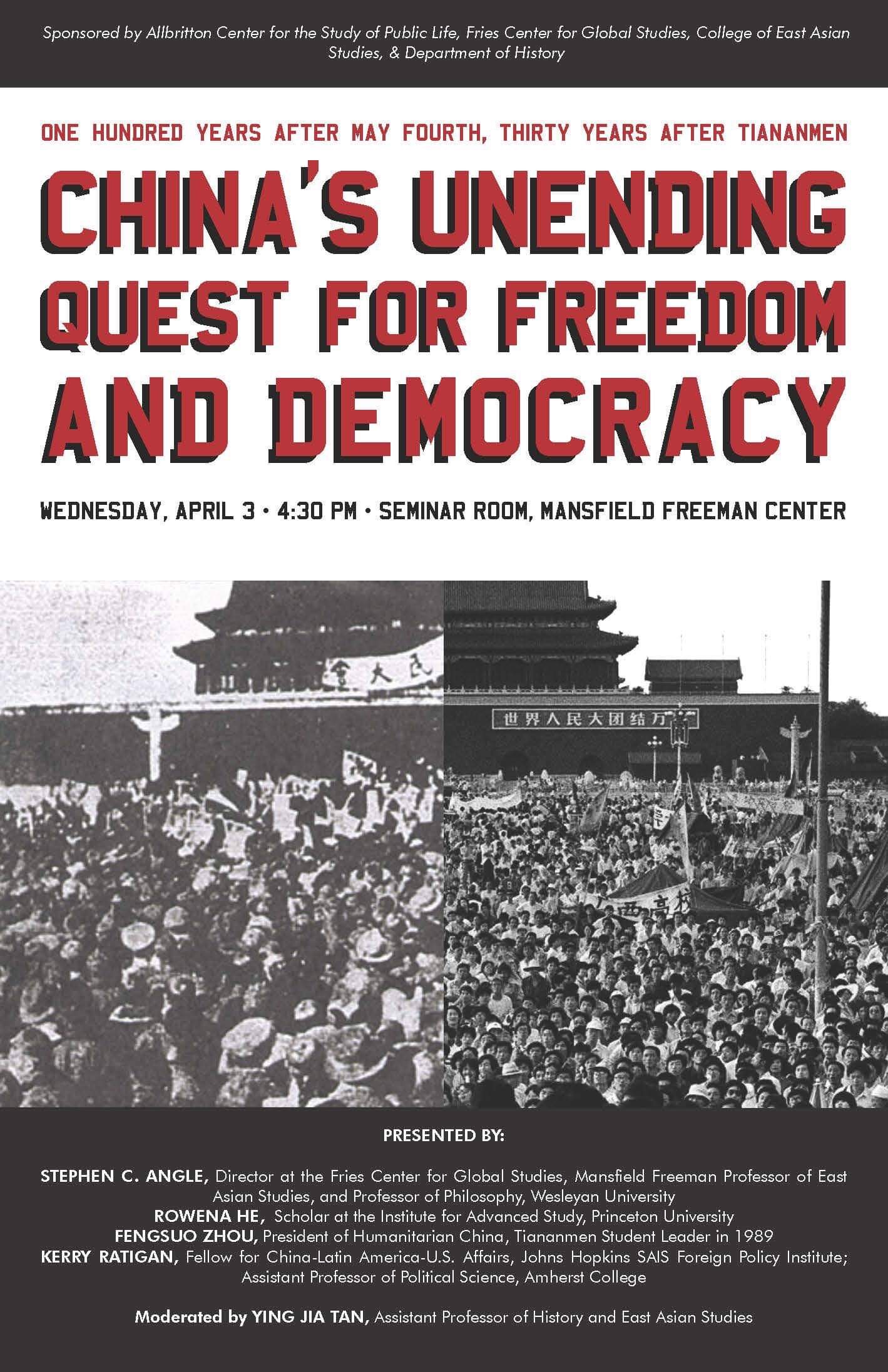

Speakers at the April 3 panel “China’s Unending Quest for Freedom and Democracy” recalled and contextualized in the current moment two historic student movements in Chinese history: the May Fourth Movement in 1919 and the Tiananmen Student Movement in 1989. The panelists emphasized the importance of the student movements in the contemporary political moment and highlighted the Chinese government’s efforts to change narratives around the movements and to prevent similar occurrences in the future. The panel featured, in addition to an exiled Chinese student activist, researchers studying state-society relations, philosophy, and intellectualism in China.

The panel was moderated by Assistant Professor of History Ying Jia Tan and was hosted at the Wesleyan Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies. The speakers were Mansfield Freeman Professor of East Asian Studies Stephen Angle, Member of the Institute for Advanced Study Rowena Xiaoqing He, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Amherst College Kerry Ratigan, and Fengsuo Zhou, an exiled student leader who closely participated in the 1989 Tiananmen Movement.

The two movements at the center of the panel are considered pivotal historical moments in which students took to the streets and became the leading voices pushing for substantial political changes. The first was the May Fourth Movement, which refers narrowly to students in Beijing protesting against the Chinese government’s weak response to the reluctance of imperial powers to return Chinese territories that had been ceded during World War I.

Tan explained that the Tiananmen student movement, which occurred 70 years later, had similar elements, including student energy, an internationalist agenda, and a violent tinge. The movement consisted of a series of nationwide demonstrations calling for civil rights, such as democracy and the freedom of speech. The military cracked down on one of these demonstrations in Beijing on June 4. That night, troops with assault rifles and tanks fired at the protestors, who were trying to block the military’s advance towards Tiananmen Square. It was more commonly known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Western media representation and remembered with a photo of a man standing and confronting a row of tanks alone. Anywhere from a few hundred to over 10,000 people were killed, with the Chinese government claiming that under 300 were killed while contemporary historians place the number much higher.

After Tan’s opening remarks, Angle gave an overview of the changing meaning of the intellectual and cultural legacy of the May Fourth Movement within different periods of modern Chinese philosophy, based on the book “The Chinese Enlightenment” by Wesleyan Emerita Professor of East Asian Studies and History Vera Schwarcz. He emphasized the importance of examining the influence of historical events on modern political contexts and the ways in which this examination can shed light on the present through rediscovering the past.

“One of the themes, as Professor Schwarcz puts it, is that there is a new May Fourth for each generation,” Angle explained. “The last chapter of the book is actually called ‘May Fourth as Allegory,’ in which what she means by allegory is reconstructing memory for the…purpose of instructing the present. I think this is a really important idea for us to keep in mind as we talked about [the legacy of May Fourth] because we are remembering this event in the context of the present moment.”

While the meaning of the May Fourth Movement has been reframed and co-opted in different periods—ranging from being utilized to justify further communist revolution in the early 20th century to a liberal antecedent which civil rights activists paid homage to when the civil society in China revived in the early 2000s—Angle concluded that one core element that they all share is the spirit of criticism.

“So, to genuinely accept and endorse the legacy of May Fourth today is precisely to continue to question what the legacy of May Fourth is today,” Angle concluded.

The second speaker, Fengsuo Zhou, was a key student leader in organizing the democratic movement in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Zhou was fifth on the 21-most-wanted list of student leaders after the government crackdown, and he came to the United States after he was imprisoned and his passport was revoked for years.

In his talk, Zhou gave a detailed account of his personal involvement in the 1989 Tiananmen Student Movement as one of the student leaders. He recalled how thrilled he was when printing his own words on a university’s walls to call for freedom of speech. He also recounted his experience working as a member of a radio station on covering the Tiananmen Student Movement, encouraging students who were on a hunger strike.

“[The student movement] is the most important moment in my life,” Zhou said. “It was like a volcano eruption, so splendid, wonderful and then suppressed violently and forgotten.”

While, for the sake of time, he wasn’t able to cover the last stage of the movement when the crackdown happened, he drew the audience’s attention to earlier moments within the movement, when people across all fields were calling for democracy.

“What we remember about the June fourth—most people remember the massacre, the bloodshed,” he explained. “But what happened before that: That is what we need to remember. That was very inspiring—what the students [and] people of Beijing and all over China were doing—the overseas students here, and in Hong Kong, Taiwan. It was one moment when this dream of freedom and democracy unifies everyone in China and outside of China.”

The third speaker, He, presented a critical view of the narrative adopted by the Chinese government to characterize the Tiananmen Student Movement as a “counter-revolutionary riot” rather than what she considers a patriotic movement—as the May Fourth Movement has been characterized.

“Later [after the crackdown], the government named that ‘counter-revolutionary riot,’ meaning that they were trying to overthrow the government,” He explained. “In political science sense, it was a revolution, they were hoping for revolution—that was a lie. Because the students, from day one, were following the Chinese tradition of Confucian dissent, according to Merle Goldman. So there was not a revolution, they never tried to overthrow the government.”

The last speaker, Ratigan from Amherst College, addressed how the relationship between state and society has transformed after the Tiananmen Student Movement, with the former developing tools to strategically repress the latter and thus cause society as a whole to struggle to survive. Ratigan drew upon her study of the protests and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in China to explain how the Chinese government has adjusted its approach to social suppression after the Tiananmen Student Movement.

“Over time, repression from the state becomes far more surgical, so rather than using sort of a grand hammer—‘Oh, now we have to clear the square’—they become far more strategic,” she explained.

During the Q&A session, students asked several questions regarding issues raised during the talk, and most questions were centered on one core issue: the prospect of a democratic future for China. While present-day Chinese politics don’t indicate such a change—at least not in the foreseeable future—they did end the panel on an optimistic note.

“Eventually, history is on our side,” He said. “I have to be hopeful and optimistic in the sense that [democracy will come about in China] maybe not in my lifetime, but maybe in yours.”

Whiskey Liao can be reached at wliao@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed