Jodie Kahan

Maybe We Should Interrogate Our Studio Art Department

Media • February 21 • Jodie Kahan

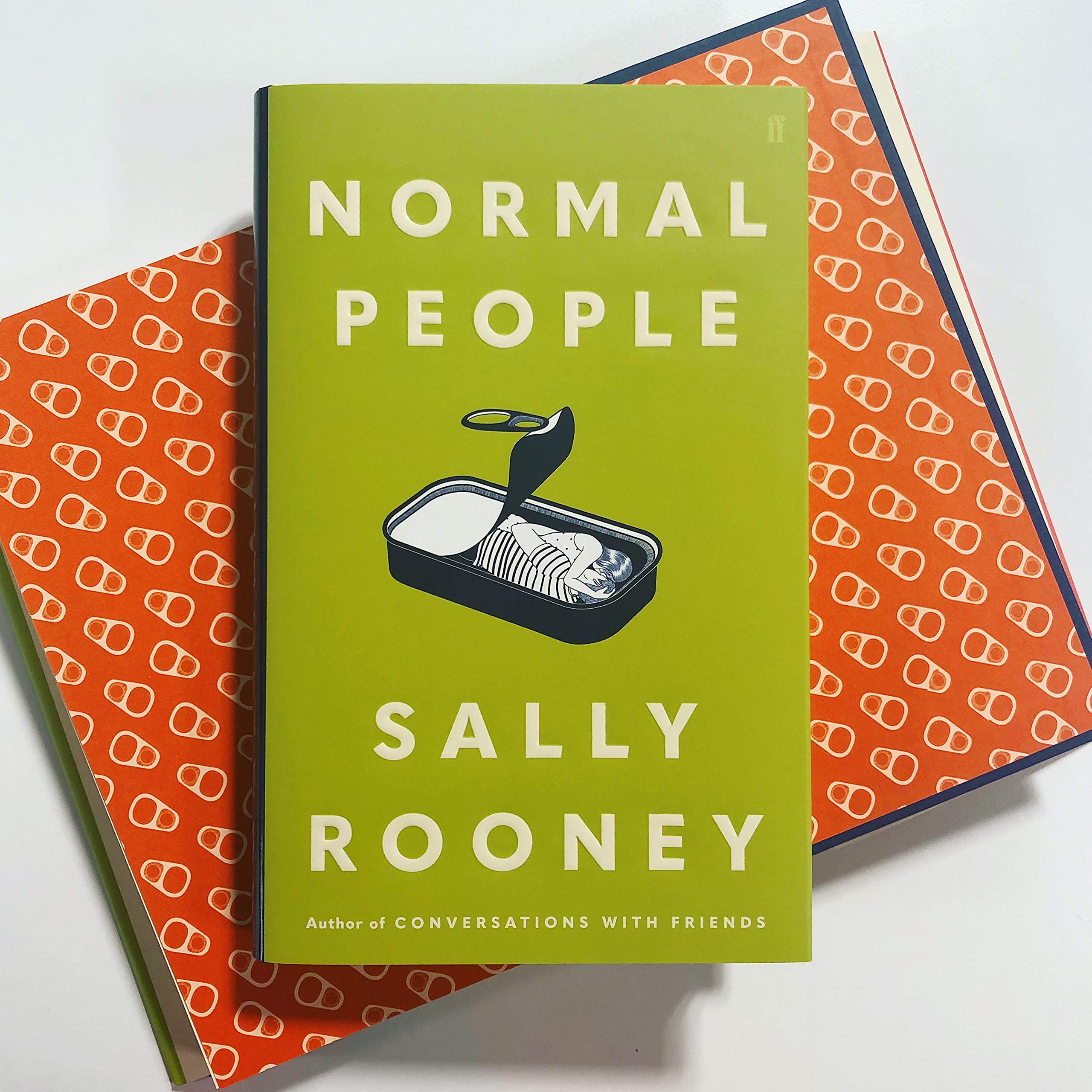

“Normal People” Is a Sharply Authentic Portrait of Modern Love

Arts & Culture • May 3 • Jodie Kahan

All My Little Words: War and Peace and Modern Love

Arts & Culture • February 14 • Jodie Kahan

An Open Letter to Jonah Hill

Arts & Culture • December 3 • Jodie Kahan

“Hadestown” Retells Old Myths With New Meaning

Arts & Culture • November 29 • Jodie Kahan

Local Restaurant B&B Wings Challenges Conceptions of Vegan Culture

Arts & Culture • November 15 • Jodie Kahan

“Legally Blonde” Brings Infectious Energy and an Uplifting Message

Arts & Culture • November 15 • Jodie Kahan

All My Little Words: Grunge, 25 Years Later

Arts & Culture • November 5 • Jodie Kahan

Kahlil Robert Irving Installs New Exhibit in Zilkha South Gallery

Arts & Culture • October 25 • Jodie Kahan