Twice a week this past summer term, some 20 students at the high-security Cheshire Correctional Institution—about a 30-minute drive from Wesleyan—poured into the prison’s resource room, a stuffy gymnasium that has been converted into a library. Carrying sketchbooks full of drawings that they had worked on over the summer, they headed to an introductory drawing class offered to incarcerated students by Wesleyan.

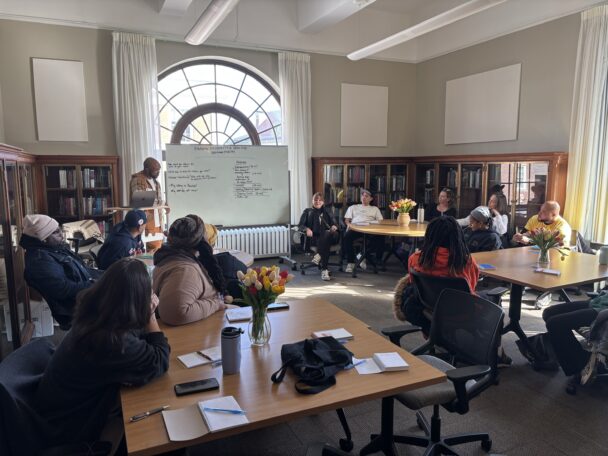

The class, taught by Associate Professor of Art Julia Randall, was a summer course offered by the Center for Prison Education (CPE). The CPE, founded in 2009, is a Wesleyan initiative that offers courses at the Cheshire and York Correctional Institutions for degree-seeking students incarcerated within the two prisons. The program allows students to complete an associate’s degree and, as of 2019, a Bachelor’s in Liberal Studies (BLS). The BLS degree comes with academic advising and mentoring from the University’s Writing Center.

Exploring Academic Options

The summer drawing class supplemented two regular Spring and Fall semesters organized by the CPE, during which Wesleyan faculty teach classes ranging from bioethics to microeconomics. A smaller summer semester was added in 2024 to promote year-round engagement in the program.

Every two years, prospective students with at least 18 months left on their sentence can apply to enroll in the associate’s degree. The application process includes two essays and a final interview with two Wesleyan faculty. Students can also attend a mock class. Each cohort at Cheshire is around 18–20 students; cohorts at York range from 12–15 students.

The program has grown in the past years, expanding especially within the York prison, which had only four students during the pandemic. By January 2026, that number will have grown to 32. At Cheshire, total enrollment grew from 30 students during COVID-19 to around 45 in January.

“We really have invested a lot of attention in building back at York,” Director of the Center for Prison Education Tess Wheelwright, who has been leading the program since 2023, told The Argus. “[There was] almost a moment of, ‘Are we overstretched?’ We did some strategic planning and consulted with alums and decided to pour a lot of love and attention [into York].”

Each admissions cycle is preceded by an outreach campaign to explain the degree program to potential students and dispel myths. At York, educational opportunities offered by other schools, including a six-course marketing certificate program run by Connecticut State Community College Three Rivers, exist alongside the Wesleyan associate’s degree.

“[Some students say,] ‘We see those Wesleyan students. They’re always carrying 15 books. I’m not sure that’s for me,’” Wheelwright said. “Sooner or later, [they] seem to pop up and transfer to our program.”

The program has not always been met with such an endorsement.

“I heard about the college-in-prison education program in its initial stages…and I was a bit skeptical about the program,” Shakur Collins ’26, a graduate of the associate’s degree program currently pursuing his BLS on the Wesleyan campus, told The Argus. “Part of my critique…is that there’s this idea that if people have access to education, that somehow resolves the larger issues of mass incarceration.”

Collins, who began his BLS in Fall 2024, is now working towards completion of his degree on Wesleyan’s main campus. He also works as the CPE’s public relations associate. Collins’ initial reservations about education in prison were tempered as he spoke with friends who had participated in the program.

“I was able to see firsthand…that [the CPE] was building community, which for me is an essential thing,” Collins said. “Ultimately, that’s why I decided that I wanted to take the opportunity to be a part of that community.”

Adjusting to Challenges

Although the CPE program is widely known among incarcerated people at Cheshire and York, it can accommodate only a small portion of those interested. There is not sufficient space nor technological support to provide widespread access to the program, leaving a majority of qualified incarcerated people outside of it.

Indeed, a desire for greater access is a recurring theme across the program’s students and staff. Classroom space is extremely limited within both prisons, and security measures create time-consuming roadblocks. Syllabi must be approved in advance, as must any videos to be shown during class. These resource constraints restrict how many classes can be offered—currently seven at Cheshire and four at York—and thus the number of students who can be admitted.

The constraints on teaching were especially strenuous during the summer drawing class. A delay in approving drawing materials left Randall and her students with nothing but ballpoint pens and printer paper, far from the plethora of charcoals, pastels, and paper handed to drawing students on the main campus on the first day of class.

“You have to be so flexible if you’re teaching there, because it’s an institution…where I am absolutely not the queen of my domain,” Randall told the Argus. “I’m there through their grace…you have to play by their rules.”

However, a spirit of ad hoc solutions and perseverance persists across the CPE staff.

“It’s always entertaining and inspiring to see new faculty adjust to…the logistics of trying to do what we do,” Wheelwright said.

CPE staff and faculty described being motivated by the ironclad commitment of students to the continuation and quality of the program.

“It gave me a great deal of pleasure to teach these students,” Randall said. “They’re phenomenally dedicated, appreciative, non-privileged; my students were 100% in it to win it.”

This dedication leaves students wishing for more access to the full range of courses offered on Wesleyan’s main campus, which they often hear about during study halls with teaching assistants.

“The incarcerated students get a lot of information [from TAs] about the rest of the course catalog and the rest of the universe of Wesleyan and then end up asking about it and posing the challenges to us on how to bridge to some of the rest of that for them,” Wheelwright said.

Some classes, like dance, remain a logistical challenge to be confronted. But the drawing class, which will be taught again in the spring, was the first of what is hoped to be a more comprehensive collaboration between the CPE and the Center for the Arts. Students’ final projects from the class were shown in the newly opened Fries Arts Building in Middletown.

The CPE has grown not only within the prisons, but on Wesleyan’s main campus as well. Student positions for teaching assistants to assist during study halls have become quite competitive, according to Wheelwright.

“It’s a truly collaborative environment, in a way that I don’t always feel about Wes classes on the main campus,” Josie West ’26, the current TA for Professor of Science and Technology Lori Gruen’s bioethics class, told The Argus. “It’s probably my favorite thing I’ve done at Wes.”

Professors can be harder to find. Because CPE classes count as overload—meaning they come in addition to the regular course load faculty must teach—many professors are reluctant to divert resources away from the main campus. The Faculty Advisory Committee of the CPE is exploring whether CPE classes could become part of a rotating load for professors across departments.

However, the difficulty does not come from a lack of enthusiasm. Professor Randall had wanted to teach a drawing class [for the CPE] for several years. Over 90 professors have taught a CPE class.

Looking Forward

For faculty and TAs, the classes can be a formative experience.

“I was nervous about navigating the power dynamic of TA versus student despite being significantly younger than a lot of [students],” West said. “But after I got to go to the first class and after I met them all, it kind of all fell into place and grounded our relationship in a nice way.”

Professor Randall expressed similar initial worries about teaching as a visitor to a place with which she had no experience.

“There’s a little bit of a thing before you start about, you know, what is the power dynamic going to be?” Randall said. “But I got nothing but full-on respect from these guys. [There was] more so, frankly, than [from] my Wesleyan students.”

Teaching in the prison forced West to challenge preconceived expectations.

“I went into it expecting to have a very adversarial relationship with the correctional employees,” West said. “It’s been really interesting to see how a lot of the correctional workers are really similarly invested in the educational development of our students. There have been challenges reconciling my own pretty abolitionist personal beliefs with the way that I’m seeing these correctional employees interacting with the students.”

Even as the CPE continues to grow and build community—with over 60 associate’s degree graduates and 20 BLS graduates—it faces challenges. One of these is ensuring that students continue to have a support structure once they leave the prison.

“I have more and more people who are coming home and are like, ‘How do I actually use this paper that you gave me?’” Center for Prison Education Program Coordinator Shirley Sullivan ’21 told the Argus. “One place of growth that we’re aiming for is to eventually have a re-entry coordinator to help people come home and integrate into the campus community.”

For many formerly incarcerated students, the University can be an incredibly tight-knit community.

“The only time I really feel like I’m in community is when I’m in [the CPE office],” Collins said. “It’s about being with people who were intentional about making contact with me as a formerly incarcerated person.”

Another difficulty is funding, although the reinstatement of federal Pell Grants for incarcerated people in 2023 has eased the pressure. The University waives tuition and fees for students within the prison, and this year, it began offering three fully funded scholarships for BLS students exiting prison to continue their studies in Middletown. The operational costs of the CPE are funded by numerous foundation grants and small donations.

As the program continues to grow and its alumni network widens, the goals of the CPE remain constant: providing high-quality liberal arts education to incarcerated students in Connecticut and helping them move beyond prison. The challenges of access and awareness, however, remain constant as well.

“It’s really just trying to bring more light to this program,” Collins said.

He quickly corrected himself.

“The light, we’ve got that one. But more attention to it for sure.”

Leo Bader can be reached at lbader@wesleyan.edu.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the six-course marketing certificate program was run by Connecticut State Community College Middlesex; it is run by Connecticut State Community College Three Rivers.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the total number of incarcerated students at York Correctional Institute, writing that there are currently 32 students enrolled; the current number of students is projected to reach 32 by January 2026.

Leave a Reply