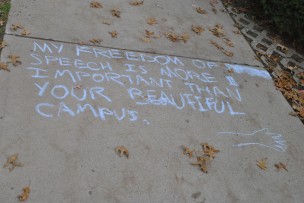

Wesleyan University is now just under halfway into the 11th year of a blanket moratorium on chalking on campus property. The moratorium (or perhaps we should just call it a ban since there is nothing to suggest that this is a temporary limitation), announced on Oct. 3, 2002 in a campus-wide email by then-President Douglas Bennet, was justified on the grounds that “[c]halking, as practiced, undermines our sense of community and impedes substantive dialogue.”

While both Presidents Bennet (1995-2007) and Michael Roth (2007-) have provided justifications for the ban on chalking, both arguments appear to be predicated on the notion that, because Wesleyan is a private institution, the University has no responsibility to state or federal protections of freedom of speech. As a result, student response to the ban over the course of the last decade has focused on the ethical issues surrounding a suppression of speech and not the legality of the moratorium itself.

However, state law suggests that this story is not so simple. It is time, therefore, for the dog to bark—for students to look critically at the prohibition to see whether the University is enforcing an illegal policy and, more broadly, what rights we as students have to speak within our privately owned ivory tower.

In this article, it will be argued that Wesleyan’s chalking ban is facially unenforceable because it violates Connecticut state law, specifically Connecticut General Statute §31-51q, which, in brief, protects some employee speech from infringement by an employer. The chalking ban is overbroad in that it prohibits some legally protected speech—for example, that of students who are employed by the University—and therefore is an invalid policy that should no longer be imposed until sufficient considerations are made regarding free speech rights on campus.

Federal Constitutional Protections of Free Speech

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution affirms that “Congress shall pass no law…abridging the freedom of speech.” Although the Free Speech Clause now applies to state governments under the Fourteenth Amendment, Gitlow v. New York (1925), constitutional protections in general do not ordinarily extend to infringements by private actors. DeShaney v. Winnebago County(1989). This is to say, for example, that an individual does not have the constitutional right to enter the house of another person to preach to her. Private actors, such as people or institutions that are not affiliated with the government, are able to infringe upon the speech of others without constitutional recourse.

Thus, the first question to ask when determining the legality of the chalking ban is whether the University is itself a private actor.

In Marsh v. Alabama (1946), the Supreme Court found that “the more an owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for use by the public in general, the more do his rights become circumscribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of those who use it.” However, in Rendell-Baker v. Kohn (1982), the Court later refused to consider a privately owned school to be a state actor, even though the school received money from the government and the school served a genuine public function. It appears, then, that there is little argument that could be made that Wesleyan University is not a private actor for the purposes of the First Amendment.

However, there are a few caveats in the jurisprudence subsequent to Marsh that require exploration. PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins (1980), for example, suggests that, although limitations on speech by private actors may not trigger federal protection, state constitutions may confer expanded speech rights than the federal constitution requires. In this case, the Court determined that the California state constitution codified much broader protections for free speech than the federal constitution, and the more expansive state constitution should be respected in instances such as these. Similarly, Hudgens v. NLRB (1976) explains that state laws “may in some situations extend protection or provide redress against a private corporation or person who seeks to abridge the free expression of others.”

Thus, if we do not dispute the claim that Wesleyan is a private actor, it appears from Marsh, Hudgens, and PruneYard that the University may still be limited on the types of speech it can infringe upon by both the Connecticut state constitution and also state law.

Connecticut State Constitutional Protections on Free Speech

Following PruneYard, the state constitution may trigger broader free speech protections than the federal constitution. For the purposes of free speech, the most relevant sections of the Connecticut Constitution would include §4 “Every citizen may freely speak, write, and publish his sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty” and §14 “The citizens have a right, in a peaceable manner, to assemble for their common good, and to apply those invested with the powers of government, for redress of grievances, or other proper purposes, by petition, address, or remonstrance.” (For religious speech, §3 will also be implicated.)

According to the Connecticut Supreme Court, however, the Connecticut Constitution is not expansive enough to protect speech against infringement by private actors. In Cologne v. Westfarms Associates (1984), the state court determined that there was “no evidence [in the Connecticut Constitution] of any intention to vest in those seeking to exercise such rights as free speech and petition the privilege of doing so upon the property of others” (on page 59 suggesting that this even applies to private university property). Thus, unlike California in PruneYard (or New Jersey, Colorado, Oregon, Massachusetts, Washington, and Pennsylvania similarly), the state constitution of Connecticut does not enshrine free speech protections when dealing with private actors.

Connecticut Statutory Protections on Free Speech

However, as noted in PruneYard, “a state may adopt, in its own constitution, individual liberties more expansive than those conferred by the federal constitution and a statute is, for that purpose, in the same category as a state constitution.” Thus, it is possible that some refuge can be found in state law for questioning the legality of the chalking ban.

Although there is no statute that protects all individuals from having their speech restrained by private actors, there appears to be some limitations that exist specifically to protect the speech of employees. Connecticut General Statute §31-51q holds that “Any employer…who subjects any employee to discipline or discharge on account of the exercise by such employee of rights guaranteed by the first amendment to the United States Constitution or section 3, 4, or 14 of article first of the Constitution of the state, provided such activity does not substantially or materially interfere with the employee’s bona fide job performance or the working relationship between the employee and employer, shall be liable to such employee for damages caused by such discipline or discharge…”

Simply put, employees are afforded legal protections against discipline or discharge from their employers for speech if (1) that speech is otherwise constitutionally protected, and (2) that speech does not substantially interfere with job performance or a working relationship. This understanding, albeit somewhat more limited, was affirmed by the Connecticut Supreme Court in Cotto v. United Technologies (1999): “We conclude that §31-51q applies to some activities and speech that occur at the workplace because…there is no prohibition that prevents a legislature from protecting employee speech wherever it occurs.”

However, Cotto did provide some further qualifications. According to Cotto, §31-51q parallels federal statute 42 U.S.C. §1983, and thus Supreme Court interpretations of that law should inform state law as well.

According to the Supreme Court in Waters v. Churchill (1994), in order to be protected by Section 1983, “the speech must be on a matter of public concern, and the employee’s interest in expressing himself on this matter must not be outweighed by any injury the speech could cause” to employee relationships. Similarly, in Connick v. Myers (1983), the Court found that “conduct at a governmental employer’s workplace is not constitutionally protected unless the expressive activity concerns a matter of public, social, or other concern to the country.” Finally, although not mentioned in Cotto because it was not at issue in the facts of the case, Section 1983 can also protect religious speech, including religious speech that does not abut national concerns. Rosenberger v. University of Virginia (1995).

Following the Court in Cotto, it therefore appears that any employee, including student employees, can invoke §31-51q for employer discipline as a result of their speech if (1) the speech is otherwise constitutionally protected, (2) the speech does not substantially interfere with job performance or the working relationship, and (3) the speech is either religious or of pressing national concern.

To be sure, there exist some forms of speech that can meet all three above requirements. As a result, the University cannot, without second thought to civil liberties, ban any and all speech that it dislikes. In the state of Connecticut, some speech cannot be infringed upon, even by private employers.

For chalking to be protected by §31-51q, we must first argue that chalking is constitutionally protected speech. From there, it would likely be most useful to next argue that the moratorium is facially invalid because of overbreadth—it does not allow for speech that withstands prongs two and three above to survive on University campus despite legal protection.

Leave a Reply