Ukrainian Scientists Discuss Academic Freedom and Research During Wartime

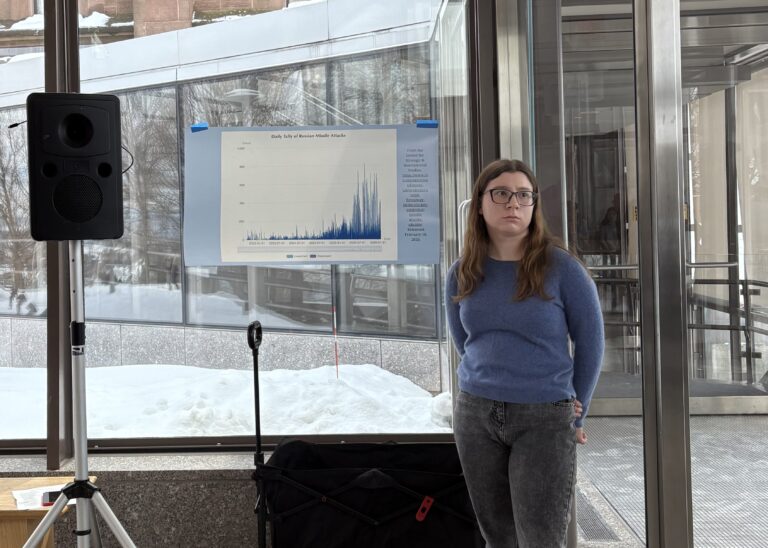

On Thursday, Feb. 5, students and members of the University community packed the Fries Center for Global Studies to hear stories of Ukrainian resistance and discuss how academics can survive attacks on scientific truth.

“War is a stress test for science in all realms,” Svitlana Andrushchenko, Associate Professor at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv and advisor at the Ukrainian Ministry of Energy, said.

The discussion highlighted the work of Ukrainian scientists who have resisted oppression in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion and occupation of Ukraine. It is a continuation of “Standing with Ukraine,” a series of livestreamed conversations hosted by the University with students and experts in Ukraine started in 2022.

The event was co-sponsored by the U.S. branch of Shevchenko Scientific Society, a Ukrainian organization focusing on scholarly research and education, and hosted by Associate Professor of Russian, East-European, and Eurasian Studies (REES) Katja Kolcio.

Hosted panelists were the picture of Ukrainian resistance.

Alongside Andrushchenko, speakers included Oleksii Boldyriev, who holds a doctorate in experimental biology and works to highlight the repressed legacies of Ukrainian scientists; Kyrylo Beskorovainyi, a co-founder of the Science at Risk initiative and a 2025 Nieman Fellow at Harvard; and Yulia Bezvershenko, the Ukraine Lead at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics and a co-founder of Science at Risk. Moderating the event was the Director of the Bailey College of the Environment Barry Chernoff.

Three researchers joined the talk virtually from besieged Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital and largest city.

The city has endured Russian drone and missile attacks since the beginning of the full-scale invasion in 2022 and continues to reel from rolling blackouts caused by Russian attacks on energy infrastructure; many other cities in the country have also gone without heat and other essential services.

Panelists spoke to the vital role of Ukrainian research during both war and peacetime. Science at Risk, an initiative to connect Ukrainian scientists to the academic community in the United States and Europe, has worked to share these stories more widely.

“Ukrainian scientists have accumulated very valuable information that can help not only [within] Ukrainian contexts, but also throughout the world,” Beskorovainyi said during the panel.

The panel offered insight into the importance of academic research and writing during periods of political and social upheaval, an experience familiar to Ukrainian scientists who have continued to survive and work during conflict for over three years.

Andrushchenko’s work centers on geopolitics and security, and he emphasized “resilience, recovery and reconstruction” in future Ukrainian scientific endeavors and energy policy.

Students in attendance were grateful for the focus on Ukrainian academic and scientific excellence, noting it as a welcome shift from the typical focus on combat.

“I appreciated that this topic was raised because, amid the many horrors of war, less visible yet profoundly important consequences—such as the damage to science and education—are often overlooked,” Ukrainian student Yehor Mishchyriak ’26 wrote in a message to The Argus.

In Kolcio’s introductory remarks, she emphasized the global importance of Ukrainian scientists as the profession itself comes under increasing attack around the world. To Kolcio, the resilience of Ukrainian scientists far predates the most recent Russian aggression.

“Throughout the twentieth century, Ukrainian scientists were systematically persecuted, denied institutional support, and cut off from resources,” Kolcio wrote in an email to The Argus. “When research is silenced, scientists displaced, serving on frontlines, or otherwise prevented from working, the consequences are global.”

Kolcio spoke to the importance of student activism for spreading awareness about Ukrainian resistance.

“Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and even before, Wesleyan’s Ukrainian students have been actively organizing campus events focused on current events, film, culture, and language, as well as advocating directly with Connecticut state representatives,” Kolcio wrote.

Those in attendance reflected on the importance of scientific advocacy during wartime, given the increasingly tenuous position of many scientists working in Ukraine.

“The panel today really put into perspective exactly how much science is and has been at risk in the Ukraine,” Kate Battaglia ’27 said. “One power outage can lead to the loss of years’ worth of scientific research, and findings [might not] be recoverable.”

Students and panelists noted a connection between the pressures on scientists in Ukraine and the recent Trump administration attacks on intellectual freedoms in the United States. Although their day-to-day experiences are vastly different, academics in both countries risk being victims of the politicization of scientific thought and freedom.

“This issue extends far beyond Ukraine,” Mishchyriak wrote. “In the United States, a global leader in science and education, current political actions threaten academic institutions—as seen in attempts to coerce universities like Harvard through massive financial pressure.”

Panelists echoed the sentiment, stressing that the lessons learned in Ukraine might better inform resistance to authoritarianism and anti-intellectualism elsewhere.

“We can teach Americans how to defend their rights,” Boldyriev said.

University students can see the work of the Science at Risk team in the Science Library. The “Freedom in the Equation” exhibit highlights Ukrainian scientists that were killed by Russian aggression and who have otherwise been robbed of the opportunity to pursue their careers. The exhibit features portraits of 10 scientists painted by Niklas Elmehed, the official artist of the Nobel Prize.

Kolcio, Chernoff, and REES Chair Susanne Fusso submitted the proposal in order to teach Wesleyan students more about the role of Ukrainians in science.

“Simply learning about Ukraine from Ukrainians is an act of historical correction,” Kolcio wrote.

Anabel Goode can be reached at agoode@wesleyan.edu.

Miles Craven can be reached at mcraven@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply