Dear Protestors, Where Are Our Firebrands? A Critique of Wesleyan Dissenters

How terrible are the actions of ICE agents in Minnesota! I plan to send my heartfelt condolences, or maybe sympathy cards, to reconcile the dystopic scene proliferating across the country. Even better, I could attend an anti-ICE protest on the New Haven Green and—amidst the whopping turnout of four members per organization—implore the city council to write a toothless resolution.

At Wesleyan, protests and rallies are just as prevalent as they were 40 years ago, partly thanks to a president who champions free speech. Only a year ago, protestors erected encampments in solidarity with the emancipation of Palestine. The coalition of groups demanded divestment from certain companies with financial ties to Israel, which mirrored similar demands from students at peer schools. The University administration respected their “right” to pitch tents, cosseting the advocates while fostering the fabulous environment Wesleyan is all about.

Like many on-campus demonstrations, the Wesleyan activist’s greatest moment of rebellion fell short, not only of the movement’s goals but of genuine rebelliousness (the Board of Trustees rejected their demands for divestment four months after negotiations settled for decampment). In the heyday of geopolitical crises, we are surrounded by circumstances that require unprecedented action, yet campus zeal ebbs and flows per usual.

Increasingly, student leadership’s clean-cut efforts struggle to be more than political gestures, and advocacy is seemingly unable to escape the narrow boundaries of civic engagement outlined by our administration. It is easy to fall into this trap, a trap exacerbated by the disposition of college students: On a national stage, we are quickly characterized as griping academic elites, and in the eyes of university administrators, we are seen as blossoming young adults, never quite mature enough to have a say in the future of our institution.

It may seem wrong that I take issue with lackluster calls for justice and futile attempts at organization, since Wesleyan should, of course, be a safe haven of education and growth. We are, after all, adorable little children taking our very first steps in the world of political participation. But what a pathetic excuse, considering our demographic is one of the largest catalysts of social upheaval. We make the perfect provocateurs—freshly eligible to vote, neurologically underdeveloped, and ardent pursuers of the truth.

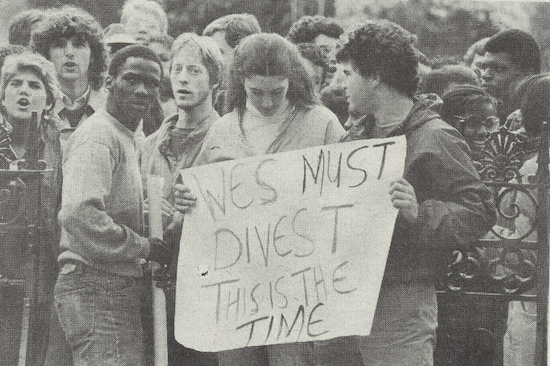

In 1985, Wesleyan recorded near record protest numbers in a clashing confrontation with the Board over the endowment’s financial ties to South Africa. More than 400 Wesleyan students stood proudly, entreating divestment from an apartheid-ridden nation. Ultimately, the University was pressured to enact more stringent requirements for companies in which it held shares that conducted business in the country. Additionally, the board provided supplemental funding for research on corporate conduct. Notably, then-University student Isaac Shongwe ’87 joined the protest knowing full well that the resulting press attention would bar his return to South Africa—a home he hadn’t seen in five years. I was taken aback by the act of courage. It seems so foreign that a student with so little to gain and so much to lose could soberly risk it all for his beliefs.

Forty years later and activism is not all but lost; another prod at radical protest took place in 2024. In another case of financial demands and campus solidarity, students staged a pro-Palestinian sit-in in the office of President Michael Roth ’78. The demonstration, while ultimately unsuccessful, did not come without repercussions. When push came to shove, police were called, outraging activists. Subsequently, a campaign to dismiss any punishment of the ten participating students ensued. The byproduct of “good trouble,” as John Lewis put it, was just on the horizon, until the students retracted. What a privilege it is to so quickly see the consequences of your actions unfold and, thanks to social media, suffer them so publicly. A fast-track to political change is on the table, but the buy-in is too expensive for most. Martyrdom is not necessary for successful political efforts, but personal sacrifice certainly is.

In a world of digital receipts and scrupulous documentation, mistakes are unforgiving—as they should be. This generation of activists is prone to preaching empty rhetoric because they live in an era written in ink. Unfortunately, many misconstrue this challenge as defeat.

Modernization is not the only dynamic that’s raising stakes. As the boundaries of acceptable protest expand, so too does the effort required to produce real change. Activists have little reason to cheer when the university they scrutinize so warmly approves of their protest, lest dissent becomes just another sanctioned learning experience. This reality sounds oddly familiar. In reference to the 2024 anti-Israel encampment, Roth said he was “proud” of the protesters, and where would the movement be without the professor-led educational experiences in the Wesleyan Liberated Zone?

Political change requires disruption, and disruption is fatefully self-jeopardizing. I see the trend beyond Wesleyan: Grassroots activism is becoming a cheap way to polish up a resume, or worse, a performance of hollow actions to comfort our guilt. A guilt—so readily displayed—that paradoxically absolves us simply by existing, turning self-reproach into a twisted form of self-aggrandizement.

Real action entails real risk, and students seem less willing than ever to swing for the fences. Perhaps radical idealists are eternally condemned to face masks, while the indifferent moderates bathe in participation trophies. Or is there honor in showing face in and of itself in an era of political cowardice and rising stakes? Time will tell, but it is clear that this is not your grandfather’s age of activism.

Beck Holtzman is a member of the class of 2029 and can be reached at bholtzman@wesleyan.edu.

This article feels a bit snarky and privileged. Why be annoyed that professors and the administration support your protests? That is a luxury compared to what basically every other college got.

Have you taken an English class before? Is your brain neurologically underdeveloped for Argus opinions? Did you just learn the word modernization? What is this gibberish?