From the Argives: When Middletown Had a Trolley From the Butterfields to Main Street

How do you get from the Butterfields to Main Street, or from Main Street to New York? A century ago, Wesleyan students would take the trolley. Streetcars painted shades of emerald green, ruby, and gold connected Middletown to campus and to railroads spanning New England. Swaying trolley cables and steel tracks once striped Middletown to an extent that is now difficult to imagine. To grasp the dissolution of a system once central to the city’s character, this week, we are reaching for the back shelf of the Argives to track the rise of Middletown’s former public transportation from the very beginning.

Before 1885: Freight Frenzy Reaches Connecticut

The Hartford and New Haven Railroad (H&NH) earned the title of Connecticut’s first railroad in 1833. The line delighted Hartford and New Haven residents, reflecting just one case of the nationwide freight frenzy that surged in the late 1800s. Middletown wanted a taste of this new wonder and eagerly awaited the fulfillment of H&NH’s plans to lay train tracks into the city. When the company decided to bypass Middletown, determined residents took the matter into their own hands. They founded the Middletown Railroad and laid 9 miles of train tracks from their hometown to Berlin, which H&NH had not skipped. Seeing the perfect expansion opportunity being laid out, H&NH purchased the locally chartered Middletown Railroad in 1848. (The abandoned tracks are still visible today, just off of Mile Lane.)

By the 1860s, Wesleyan students were already making use of these trains. An Argus satire on the “student of the period” published May 5, 1869, describes the undergraduate not in the classroom but in motion, easy to spot in public.

“You will never fail of distinguishing him in his travels,” they wrote. “He has a pleasant habit of indicating his presence in rail-road cars, depots, and places of public resort, by howling a number of senseless college songs, or by bald-faced rowdyism, and boisterous merriment.”

For Wesleyan and Middletown, the railroad coach had become an element of student life even before investors created the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad in 1872, folding most of the region’s smaller lines into one system.

On Nov. 9, 1870, the Argus published a notice of a crash on the Berlin branch. A freight train from Berlin Junction broke in two on the steep grade. The engineer noticed, backed his engine, and then realized the loose cars were “coming at a fearful rate” downhill. With no way to get out of the way, the crew shut off the steam and jumped. The impact snapped the coupler, opened the throttle, and sent the engine rolling into Middletown, where it “came crashing into the depot,” smashing a couple of passenger cars. Nobody died, but the Argus still scolded the railroad: “Why was there no brakeman on these cars? And if there was one, why [didn’t] he turn on the brake?”

Another notice from the Nov. 9 edition notes how quickly the landscape was changing. The construction of the Valley Railroad caused a carriage road along the river to move uphill and inland to make room for the tracks. The Air Line Railroad’s stockholders met, Portland voted to take stock rather than bonds, and Middletown itself now owned more than $300,000 in Air Line shares. Out on the water, stone piers for the new railroad bridge (now the Middletown Railroad Bridge) had already risen more than ten feet above the river. By 1870, railroads were not just passing through Middletown; they were rearranging its roads, its budget, and its view of the river.

By the summer of 1871, Middletown’s attention had turned from steam to streetcars. On June 30, the Argus reported that the State Senate had just granted a charter for a horse railroad in the city. The planned line would run from the ferry up Main and South Main streets to Zoar, with another line out to South Farms as far as the upper Russel factory, plus short branches to each railroad depot.

Steam trains hauled freight and long-distance passengers in and out of town, but they wouldn’t help a passenger get from the ferry to one’s boarding house, or from the depot to the factory gate. Horse-drawn streetcars promised something different: slow, frequent, local service that connected the river, shops, mills, and neighborhoods. Streetcars filled in the everyday gaps that the big steam roads left behind. As the Argus put it: “This is a convenience that is much needed.

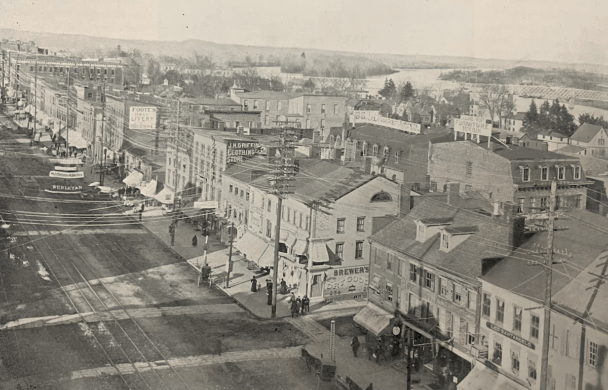

Another Argus piece published December 4, 1872, titled “A Glance at Middletown” offers a helpful description of a bygone Middletown striped with train tracks. The unnamed author describes “the town of Portland, and beneath, the city itself, with the lines of rail leading in from various directions, all combining to render the view a source of delight to all who ever saw Middletown.”

Those “lines of rail” include the New Haven, Middletown and Willimantic Railroad, which “has been running between this city and New Haven for two years,” and is “just crossing the river and pushing on toward Willimantic, through some of the most stupendous scenery in America.” Its bridge over the Connecticut River is “an iron structure, just completed.”

The same article introduced the Connecticut Valley Railroad as “a new road, skirting the west bank of the river from Saybrook Point to Hartford, a distance of forty-four miles,” which had “only been open a year, and yet its business [was] great and steadily increasing,” and “bid fair to be one of the most popular and remunerative roads in New England.”

Alongside this description, the writer noted “the Middletown branch of the New York, New Haven and Springfield,” projected lines including the Middletown, Meriden and Cheshire Railroad and the Portland and Springfield Railroad.

Middletown was “a regular stopping-place” for river boats, with “mails to and from Boston three times a day,” they wrote. “Freight and passenger facilities are first-class.”

1885: Horse Railroad

In 1885, when the Middletown Horse Railroad finally opened, private transport companies compensated for everything the streetcars didn’t reach.

Two ads printed in The Argus on June 17, 1886, give a sense of their relationship. Privately owned and operated stables, such as E. Loveland’s Livery Stable on Center Street or W. H. Smith’s on East Court Street offered horses, carriages, sleighs, and drivers “to and from the [trolley] cars and Boat [dock on the river].” The horse railroad handled predictable, fixed-route movement along Main Street, but these private stables handled everything else: late-night rides, luggage-hauling, trips beyond the streetcar line, and door-to-door transport that the streetcars simply couldn’t provide.

Livery and hack stables accommodated Middletown locals and long-distance travellers. These businesses rented “best single or double rigs” for ladies and gentlemen looking to flaunt their wealth. They provided sleighs in snowy winters, and supplied drivers for those who didn’t want—or weren’t trusted—to handle a horse themselves. In a sense, these local operations were the 1800s Uber. After departing a ferry or interurban freight train, one could decide whether to take public transit, the Horse Railroad, or hire a driver for the last leg of their journey.

1894: Electric Lines, Fiery Debates

If the horse railroad was Middletown’s public transit, these stables were its taxis, shuttles, and ride-for-hire services rolled into one.

By 1886, the horse railroad ran like a well-oiled machine and seemed only to grow in scale. As the Middletown Tribune Souvenir Edition of 1896 (at Special Collections & Archives in Olin Library) of 1896 put it, “The parent street railway in Middletown was that of the Middletown Horse Railroad Co., and the first car for public conveyance was run on its rails September 14, 1886.”

When “the demand for more rapid transit became imperative, to keep pace with other cities,” the company chose wires over horses: “as an electric railway, the line was formally opened December 22, 1894.”

The same booklet notes that “Some four and a half miles are operated, the northern terminus being at the passenger station of the Consolidated Railroad,” and that “the business portion of Main street is double tracked, thereby avoiding congestion,” with “all of the cars… equipped with the General Electric system” and trips made “with clock-like regularity.”

In its own verdict, “The advantages received by Middletown and its people from the electric railway can scarcely be overestimated.”

The Main Street Historic District fills in this picture, identifying the 1886 horse-car line as the one that, after electrification and a 1894 name change, operated as the Middletown Street Railway Company, running down the center of Main Street and storing its electric cars in a new brick trolley barn built on the former horse-stable site. By 1896, the old iron bridge built by the Middletown & Portland Bridge Company allowed those same trolleys to reach Portland, completing the four-and-a-half-mile system described in the Tribune souvenir booklet.

The arguments about what such railroads owed the public show up in The Argus. On Jan. 18, 1889, the paper reports a lecture by Yale’s Prof. Arthur T. Hadley on “The Problems of Railroad Organization,” where he tells a college audience that “the railroad is a type of modern industry, and in the solution of the problems of railroads, we may find a type of what we may expect in all our business organizations,” and insists that the real problem is not high rates but unequal ones, best handled by “commissions capable of enunciating sound and sensible decisions.”

In 1895, Interstate Commerce Commissioner Martin A. Knapp followed with a lecture on “The Relation of Railroads to Industrial Development,” arguing that “The business of public carriage is unlike all other occupations. It is a public service, not a commodity,” that “There is no natural right in the individual to operate a railroad,” and that the state “must act as a careful arbitrator for the proportionate distribution of business amongst competing lines.” At the turn of the 20th century, Middletown’s rails and trolleys were here to stay; the real question was what they owed the people who used them. That debate effectively moved through Middletown and straight into Wesleyan’s lecture halls.

Check back next next week for part two: Middletown’s public transit from 1900 to the present, featuring the end of the local trolley car and the arrival of the personal automobile.

Hope Cognata can be reached at hcognata@wesleyan.edu.

“From the Argives” is a column that explores The Argus’ archives (Argives) and any interesting, topical, poignant, or comical stories that have been published in the past. Given The Argus’ long history on campus and the ever-shifting viewpoints of its student body, the material, subject matter, and perspectives expressed in the archived article may be insensitive or outdated, and do not reflect the views of any current member of The Argus. If you have any questions about the original article or its publication, please contact Head Archivists Hope Cognata at hcognata@wesleyan.edu and Lara Anlar at lanlar@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply