The Last Hurrah: Exactly the Same

On Friday something peculiar happened. Someone cut a hole in the night and I slipped through to the morning. That is a poetic way of saying I blacked out. It all started with an all girls’ party, too much red wine and beer. I hadn’t eaten much that day. At one point we all sat in a circle and played a game: going around the circle you had to say one person in the room you’d want to be. Then one person you’d want to see naked. When one of my best friends said me I got angry. But Jane, you’ve seen me naked at the naked party! Remember smoking cigarettes we couldn’t figure out how to stamp out the butts?

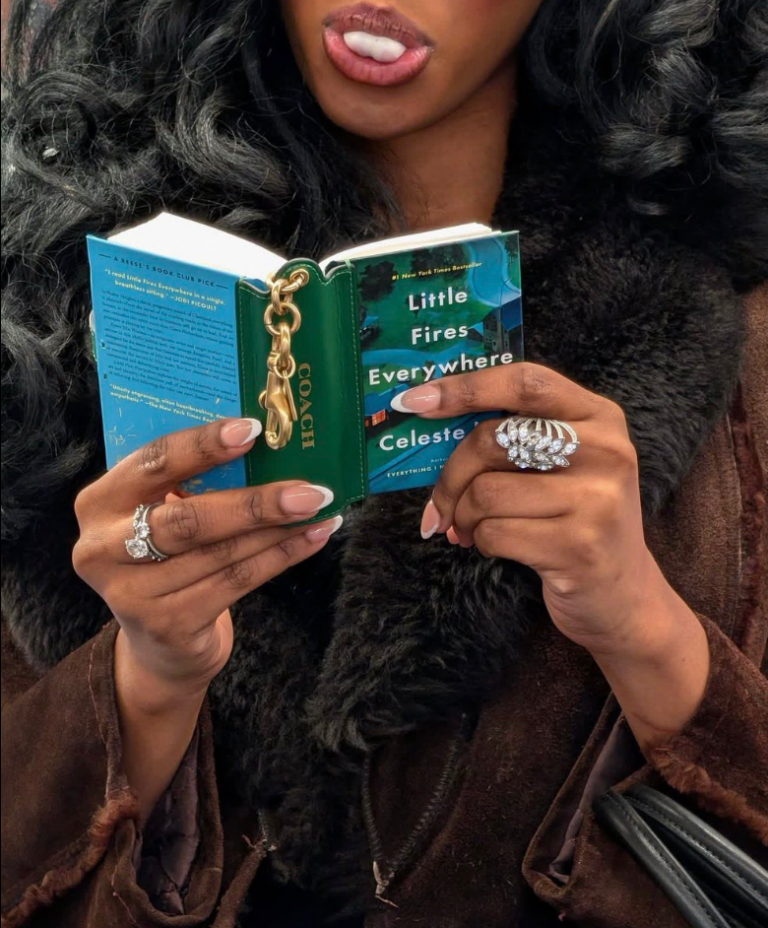

And then swoosh!It’s the next morning and I’m in my boyfriend’s bed. I’m still wearing the pink ballerina skirt I wore the night before, and my seven dollar white fur coat is on the floor. My head is in so much pain that for a whole minute I forget about my thesis, and how it is due in four days.

I spend most of Saturday wandering around campus telling people about my night, asking if they’d seen me and could help me put the pieces together. When I mention how badly I feel for going getting so trashed, and what I floozy I must have looked like in the fur coat, mumbling nonsense and accosting strangers, I get laughter and high fives.

“You are a rock star, Kate!”

“God, you were wearing the perfect outfit for that sort of behavior!”

“Kate, that is so funny! You should spend the next five years of your life doing that!”

Suddenly I saw myself as they did: an absurd caricature of me, some poor washed up version of the fresh-faced freshman who arrived here four years ago. I saw my reflection in the science tower windows and I didn’t look like a rock star. I looked like “Grandma drinks too much.” Kate, I said, in a rare moment of speaking to myself in the third person, you have to get it together before the camera crews arrive.

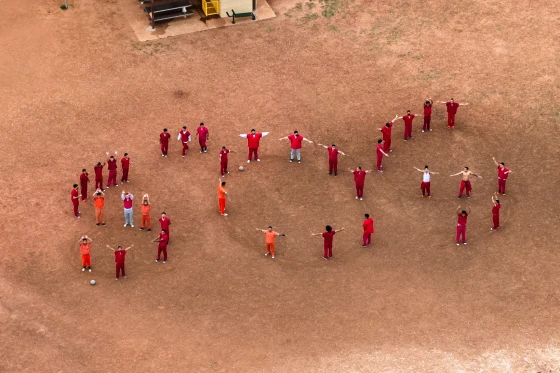

I am not sure when they are coming, but they are coming soon. Not because I write a famous column or my life is especially interesting, but because I am one of sixteen children across America whose lives are being profiled in a documentary called “Seven Up in America.” Every seven years a film crew visits me, follows me around for a day, and then asks me all sorts of flustering questions. Do you believe in God? Who are your heroes? Are you happy? I was picked at age seven when I attended a private school in Manhattan to fill the “privileged girl” quota. I’ve spent the fourteen years since trying to disappoint them. What if they could see me now? I think, glancing at my sorry reflection in the window. What if they could see me now, with my fake pearls and seven dollar fur jacket, and my red wine stained teeth? “So you were expecting a classy broad, eh? Joke’s on you,” I fantasize saying, but not without realizing that if they could see me now I’d only look like a fool.

The main question of the documentary is this: is the blue print of a person formed when they are seven? When I was seven I said some dumb things. When you are seven dumb things can sound cute. I believed in God but I had never had a religious “esperience.” You had to have a man to “get” a baby. If someone broke the uniform rule at my school I thought they should be “espelled.” When I was fourteen my parents had just gotten divorced. I was a mess but I did a pretty good job of holding it together. Or so I thought. “The shattered look on Kate’s face speaks volumes about the effect of divorce on children” one child psychologist wrote. In seven years I’d gone from cute to tragic.

The other day I met a little girl, ten years old, who had recently seen the seven year old version of the documentary. Her mother, a professor of mine, told me that she’d really liked it, liked me, and this made me shy when meeting her. The little girl was not shy. She had an amazing vocabulary and could more than hold her own with a table of professors with whom we ate dinner, something I can barely do at twenty-two.

“This is Kate, you saw Kate when she was seven,” her mother said, upon introducing us. The little girl looked up at me with wide eyes.

“This is me grownup,” I said, and immediately realized how lame it sounded. This is me grownup! This is me grownup!

Through out the dinner the little girl kept on staring at me, and studying my every move. “It’s so funny,” she said, “You are exactly the same as you were when you were seven.”

It’s very odd to be told “you are exactly the same as you were when you were seven” by a ten year old girl.

“How?” I wanted to know.

“Your gestures, the way you talk, your laugh,” she answered.

In the video when I am seven I have absolutely no poise. The whole time I’m being interviewed I’m slouched on the couch, sitting with my legs open, wearing a dress. At one point I wipe my nose with my wrist. I look bored and pick at my rope bracelet. No, I am not at all like that little girl, I wanted to say. I’ve got it together now. I’ve got better posture and a resume. I have a boyfriend who plays the accordion and a leather wallet with lots of cards in it. Cards that have my name on them! But even if I’d presented all this evidence to her, I felt like she’d see through it. I felt like she had caught on to something. That she could tell someone had cut a hole in the years and I’d slipped through.

Leave a Reply