An Anachronist for Our Time: America: red, blue and full of it

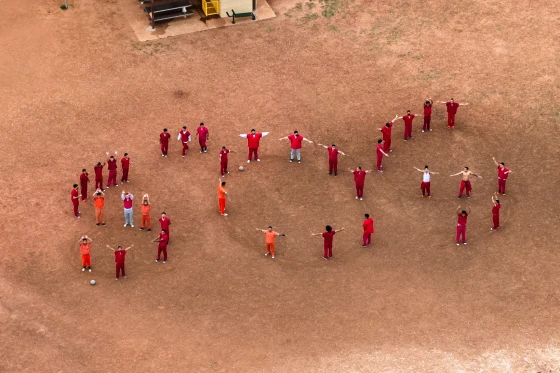

On election night, Dan Rather seemed mystified by the giant swath of red that cut across America’s heartland, warning viewers that it was not especially telling while at the same time sounding as though he believed it was pregnant with forebodings of a brewing revolution, as if the heartland would soon spill blood. He was not the only one seemingly preoccupied with the division. We are already inundated with analyses about how this election of 2004 showed the widening difference between red and blue states, and will indubitably continue to be.

Anyone with an ounce of political sophistication should realize that the distinction between red and blue states is explained largely by which states have predominantly urban populations. Voters from big cities (all of the data used in this article are taken from CNN’s exit polls, and so need to be taken as approximations with standard margins of error), who made up 13 percent of those polled, voted for Senator Kerry by a margin of 60 percent to 39 percent. Those 16 percent of voters polled from rural communities voted 59 percent to 40 percent in favor of President Bush. The suburbs and smaller cities were more evenly divided, going slightly in favor of Bush. So it seems clear that the divide in America is not between the Red and the Blue, but between the city-folk and the good country people. There is not Red Kansas or Red Missouri, but Red rural districts blanketing the nation with spots of blue at population centers. The colors that we’ve settled on are ultimately so convenient, even explanatory, aren’t they? There are the good red-blooded Americans who like hunting and go to church and believe in the sanctity of the family as the last bastion of civilization, and then there are the blue-blooded intellectuals who inhabit the great metropolises and believe that they know what’s best, in the manner of a liberal senator from Massachusetts.

This view, fortunately, is little more reflective of reality than the first. Let us take a moment to meditate over what these huge 60-40 splits in the electorate mean. Imagine that we take one hundred typical urban Americans who are qualified to vote. About 40 of them don’t, for whatever reason, leaving 60 voters (although this is slightly overgenerous). If they represent a typical big city, 36 of these voters chose Kerry, and 24 chose Bush. First of all, both of these groups are smaller than that which didn’t vote. Second, our stereotype of the liberal city dweller ought to be seriously challenged by the fact that one in four of them voted for President Bush. One in four is not an outlying exception. Similar thinking about rural districts would provide a symmetric but opposite picture.

Now think about the change in the overall popular vote from 2000, which those in the Rove Cove see as giving the President a clear mandate for these next four years. Think again of one hundred people, this time representative of the nation at large. Fifty-five of them voted in the last election, 27 each for Bush and Gore, one for Nader, Buchanan, or some other marginalized third-party man. In 2004, we’ll again suppose that about 60 of them voted, this time about 31 for Bush, 29 for Kerry.

This is the change about which the nation’s political pundits are concocting whole libraries full of theories. This is our deeply divided electorate, with two camps representing arch-nemeses, essential antitheses of one another, factions that have a hard time seeing eye to eye on most issues. America is Red and Blue (since all the networks color it that way), and if its citizens believe what the media tells them about how deeply cleft a group they are, it is full of it. Three in a hundred people who didn’t vote last time come out this time to cast their votes for Bush. Two for Kerry. One who voted for Nader last time thinks he can’t afford to “throw away a vote,” and he or she votes for Kerry. Two who voted for Governor Bush, the moderate, change their vote this time. Three who voted for Vice President Gore thought 9/11 really represented the opening of a new age in global politics and this time voted for President Bush, since you can’t change horses or ride a donkey during a war. Of course, this is pure speculation, and the real truth is that nobody will ever know exactly why such a subtle shift took place, or even if there really was one.

Perhaps, though the election should be thought of in terms of the great electoral board game engaged in by the two campaigns and their ancillary name-callers. What was a draw four years ago, with (as even the most partisan should admit) statistical chance deciding the presidency, was this time around a narrow victory for Bush achieved in the early-goings of the horse race. (The exit polls showed that, of the 78 percent of voters who decided their votes more than a month before the election 54 percent chose Bush. Kerry seems to have gained in the last month, but his famous closing ability still left him a nose short.)

If this latter interpretation is in fact more accurate, it is a depressing thing, indeed. But I prefer to think that the situation is in fact a great deal more complex than that. I even hold out a glimmer of hope that the voting public may be overwhelmingly (if quietly) disenchanted with the whole political process in our country, seeing a preoccupation with schlock in all directions. Yes, there are stirrings of hope. Mr. Ashcroft’s immanent departure is the best news for the sanity of political debate in a long time. Dallas elected an openly lesbian Hispanic woman as its sheriff on Nov. 2. Alan Keyes only got 30 percent of the vote in Illinois (on the negative side, Alan Keyes got 30 percent of the vote in Illinois).

There is hope, but it is not to be found in the moderate center. If a political spectrum has Gary Bauer, Alan Keyes, and Ralph Reed on one side, and Charlie Rangel, Al Sharpton, and Dennis Kucinich on the other, it is a spectrum I would just assume not be on at all. As best as I can reckon, the person who most thoroughly exemplifies the center of this spectrum is Joseph Lieberman, and he frankly is not the sort of political company I’d like to keep. Power in the realm of this spectrum is, I reckon, tilting to the right. But if the country reasserts its sanity sometime in the next few years, which I really think is possible, then we might even be lucky enough to get two presidential candidates who literally don’t think along this line four years from now. If it turns out I’m wrong, I’m voting for Perot.

Leave a Reply