c/o Jordan Saliby, Staff Writer

Content Warning: This article contains reference to state-sanctioned violence, anti-Semitism, and other incidents of racist violence.

In the past, the University has drawn attention for a wide range of anomalies: highly unique fashion, nude dorms, selective admissions, an open curriculum, and the stereotype that students are all liberal, artsy hipsters. While prospective students might see the University as some kind of progressive utopia, this seemingly cultivated image sparks a few questions. How did the University get its reputation? Is it really liberal? Is it progressive? We decided to head to the archives to find out.

The earliest indication of the University’s progressivism begins with the enrollment of its first Black student, Charles B. Ray, in 1832. Certainly, at this time pre-Civil War, it was an extremely progressive act to allow a Black student to enroll, but unfortunately Ray was forced to leave after less than two months, following protests by students. The Board of Trustees suspended Ray’s enrollment and declared that only white males would be admitted. The University repealed this whites-only rule in 1835, but only a few Black students were ever enrolled at the same time until 1965.

The University was also among the first colleges to enroll women in 1872. This experiment in co-education eventually ended in 1912 due to pushback from students, administrators, and alumni. Additionally, reports from the women revealed that they experienced harassment and generally felt unwelcome during their time on campus. It wasn’t until the late 1960s, that women were enrolled in the University again.

The University’s “progressivism” is said to have truly begun during the presidency of Victor L. Butterfield from 1943 to 1967. In 1943, Butterfield began what has now become the University’s open curriculum by starting the Freshman Humanities Program. This program was meant to encourage students to explore varying disciplines in order to broaden their knowledge and expertise. In 1959, he developed the College Plan, intended to completely restructure the courses of the University by replacing subject departments with broader residential colleges, which today consist of the natural sciences and mathematics (NSM), the social and behavioral sciences (SBS), and the humanities and the arts (HA) educational areas. Following President Butterfield was Edwin D. Etherington, who was President from 1967 to 1970. During his presidency, the faculty voted to abolish many of the general education requirements including a language course, science lab, and others.

Etherington was also president during the beginnings of racial integration on campus. In 1970, a New York Times article entitled “The Two Nations at Wesleyan University” was published, which outlined the stark racial divide between the Black and white students on campus in the 1960s.

“The blacks came to Wesleyan not knowing exactly what to expect; but they assumed, somewhat contradictorily, that they were entering a white paradise and also that they would be accepted—but not discriminated against—as blacks,” the article reads. “They were wrong on both scores.”

The article goes on to describe the social tensions between Black and white students and faculty on campus and argues that pressure from the Black students to recognize the relationship between the University and Middletown, University investments in South Africa during apartheid, and other issues, the University as a whole became more politically aware and active. Unfortunately, not everyone at the University was on board with incorporating such political awareness into University life.

“My Black students keep asking me what I’ve done to fight racism at Wesleyan,” a professor said. “I wasn’t hired to fight racism. I was hired to teach.”

Some professors did embrace diversifying their class curriculums by adding more content by Black authors, artists, musicians, etc. Unfortunately, many syllabi today are still sorely lacking in such content.

After being enrolled for a few years, many Black students felt that the University was taking too long to address the racial disparities on campus and began to more forcefully demand that the administration make the changes they had promised. The famous “Vanguard Class” of 1969 began to organize.

“We feel that the University has too long played her liberal white patriarchal role and that it is time that she cease considering black students as headless entities, whose only objective is assimilation,” read a statement from the students. “We will not assimilate…”

On Feb. 21, 1969, Black students, faculty, and staff staged a takeover of Fisk Hall declaring the day Malcolm X day, and issuing a list of demands to the administration.

“In occupying Fisk Hall we seek to dramatically expose the University’s infidelity to its professed goals and to question the sincerity of its commitment to meaningful change,” read the demands. “We blaspheme and decry that education which is consonant with one cultural frame of reference to the exclusion of all others.”

Following this demonstration, Malcolm X House and the African-American Institute, which is now the Center for African-American Studies, were established.

Through the 1970s, the campus’ political focus shifted to the Vietnam War. In May, 1970, almost all 800 of the University’s students voted to participate in a nationwide strike with three demands: (1) free Bobby Seale and all political prisoners, (2) get the U.S. out of Southeast Asia, and (3) end all University complicity with the war machine. The faculty voted to join and support the strike and some members of the faculty hosted teach-ins. Only a few students were vocally opposed to the strike, arguing that the University was its own world that had no impact or connection to national politics and foreign policy. The majority of students greatly opposed this position.

“Four years of the Wesleyan Experience have taught me that our fish bowl is not so sacrosanct just because it’s isolated,” Jeremy Serwer ’70 wrote in a Letter to the Editor in The Argus. “The violent, decadent, depraved, aggressive, crass, and fascist psychological bases upon which America operates can be felt right here.”

Additionally, Professor of Mathematics and Sciences Robert Rosenbaum drafted a letter to President Nixon urging him to end the war and invited other faculty members to join him in sending copies of the letter to the White House.

The 1980s and 90s saw a dramatic increase in racial tensions on campus. In 1980, a racist and anti-semitic letter was sent to Malcolm X house by alleged members of Alpha Delta Phi, which seemed to kick off decades of racist incidents on campus.

“What is this unheard-of beast? A Co-Ed fraternity, which is dedicated to wiping all goddamn n****rs off the face of the Earth,” read the letter.

In 1981, racist and anti-semitic posters were found around campus. In response, Public Safety began an escort service for minority students who felt threatened and provided special security to Malcolm X House. The posters were traced to the Fighting American Nationalists, a neo-nazi group based in North Carolina. It is unknown if students had put them up, but the campus community responded with an anti-racism rally, which around 300 students attended. Around a month after these posters were found, the Ku Klux Klan was reported on campus following a few rallies that had occurred across Connecticut.

In 1988, the University received a feature piece in an issue of Vogue Magazine entitled “Twentysomething.” The piece labeled the University as politically liberal and described the anti-apartheid protests on campus, AIDS awareness, and party culture.

“Wesleyan has seen no racial outbursts like those that have occurred at other colleges, and…a black student…insisted that ‘you don’t hear racist comments here,’” read a section of the article.

Conversely, in 1989 Dean Beckham argued that “human relations” had not been so bad on campus since the 1960s. Student protests supporting divestment and in response to racial issues became more rampant and tensions continued to increase. In January of 1990, 50 to 60 Black students took over an administration building in what they labeled the “last peaceful protest.” They attempted to present demands at a board meeting, but were unsuccessful. In February of 1990, over 100 students burned a Wesleyan flag to protest the University’s refusal to divest from South Africa during Apartheid. In April of 1990, President William Chace’s office was firebombed, AK-47 rifle shells were found on Foss Hill which were claimed by the Direct Action Group to Generate Educational Reforms, and a boat house near campus was firebombed. In May 1990, Malcolm X House was defaced with racist graffiti such as “Go Back to Africa,” “The African Damnation,” and “N****r House.”

That same month, students began a hunger strike demanding the University institute civil rights policy, address recruitment and retention of faculty of color, and divest from South Africa. The University accepted a few of the proposals, but denied that they did so in response to the strike.

Following this turbulent spring, Wesleyan witnessed a decline in Black and female accepted students who planned to attend the University in the fall. There was also a decline in in-state accepted students who decided to attend, mostly due to increased media attention about the tensions on campus.

At the same time, in the 90s the University was beginning to be recognized nationally as a progressive and free-spirited institution, despite the intense racial tensions evident on campus. A 1990 article in The Trinity Tripod entitled “How to Get into Wesleyan Without Really Trying” pokes fun at the University student free-spirited biker chick stereotype.

“I’m like your exploration guide for today,” reads a satirical quote from a tour guide. “Like here at Wesleyan we call tours ‘explorations’ because like, we believe that when you step on campus you should like, be encouraged to like, explore the diversity around you, y’know?”

In 1992, the “Common Sense Guide to American Colleges, 1991-1992” argued that the students on campus are tormented by “relentless, leftist propagandizing.” In a 1992 issue of The Argus, students disagreed.

“I feel like Wes is very apathetic,” Alex Snell ’95 said. “I don’t think it’s a political hotbed.”

Another student argued that the description was accurate for the events of 1990, but was no longer applicable.

“What they have down is the political activism from two years ago, and this campus has changed dramatically since then,” Michelle Gagnon ’93 said.

In 1998, the University was ranked the most politically active college in The Princeton Review’s college guidebook, “The Best 331 Colleges” and in 2000, the University was ranked seventh on the Mother Jones magazine list of the top 10 activist campuses.

The early 2000s also saw a number of racist incidents on campus. In 2001, a racist flyer was sent to the Chinese House program house. In 2003, a student was charged with an alleged cross burning outside of a Black student’s dorm, but there is debate over whether this was intentional. In 2006, racist graffiti was found in Clark Hall.

“This is a clear indication that Wesleyan isn’t the so-called Diversity University,” a ResLife staff member said. “We’re not immune to this.”

In 2009, a shooter who wrote in his journal about killing Jewish people and described a plan for a “Jewish Columbine” murdered a student on campus.

More recently, in 2013, there was a movement to degender the bathrooms on campus and reinstitute gender neutral housing policy. A few transgender student activists were charged with property destruction by the University for removing the gendered signs from several bathroom doors across campus. An article in Newsweek entitled “Diversity U. Makes a U-Turn” argues that this symbolized a cultural shift on campus toward declining tolerance of student activism.

In 2015, following the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, a national discussion of the limits of freedom of speech emerged in response to the publication of a racist op-ed in The Argus. The Argus faced backlash and threats of defunding, while President Michael Roth ’78 released a statement in support of its publication.

“Debates can raise intense emotions, but that doesn’t mean that we should demand ideological conformity because people are made uncomfortable,” Roth wrote.

Both The Argus and Roth received backlash from students who argued that making this an issue of freedom of speech misses the mark completely.

“Freedom of speech, in its popular understanding…protects the belief systems of dominant people,” wrote a group of anonymous students of color in response to the article.

In 2016, the University saw a wave of hate crimes following the contentious presidential election. This reminded the campus community that racism was still very much present.

“In a way, I’m not surprised,” Sarah Chen Small ’18 wrote in an email to The Argus in 2016. “I’ve seen sports teams not let people of color into their otherwise open parties. I’ve had professors threaten to lower my grade for being ‘that kid’ in class who brought up race too much. The hatred we’re experiencing now isn’t new, it’s just magnified and condoned.”

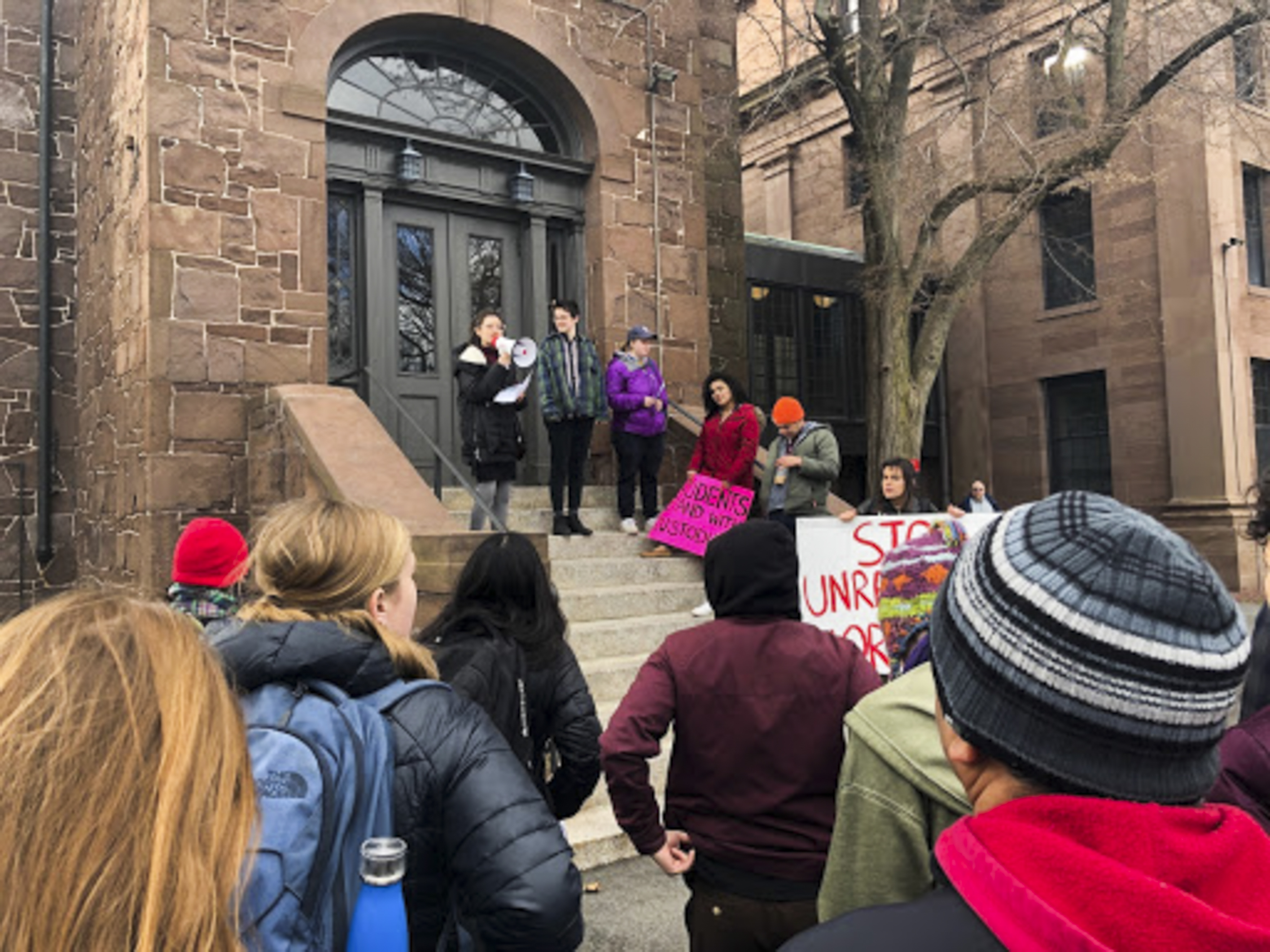

In spring 2019, the United Students Labor/Action Coalition held several protests and rallies on campus demanding the hiring of five more janitorial workers to alleviate the heavy workloads that resulted from a ten person reduction of custodial staff between 2012 and 2014. Additionally, in fall 2019, students protested in solidarity with Hong Kong protestors and against the University’s proposed joint venture with Hengdian Group in China. The University eventually stopped pursuing the venture, but did not attribute that decision to the wave of criticisms from students.

Even more recently, in fall 2020, Ujamaa, the Black Student Union, issued a list of demands to the administration covering hiring and retention of faculty of color, diversifying class offerings and curriculums, changing admissions and financial aid policies, and other issues which was heavily inspired by the demands of the 1969 Fisk Hall Takeover.

Wesleyan has had a complicated history, which is not clearly defined as progressive, but student activism has driven the administration to make progressive change. This begs the question: is the University progressive or are its students? Is there a difference?

Emily McEvoy ’22 argues that the University should not receive praise for the activism of its students.

“I think that’s kind of wack, I don’t know what else to say about it, but it’s just the fact that [activism] can be commodified,” McEvoy said. “There’s such a look at activism as if it’s something that can be coveted and also co-exist within the structures that currently exist rather than tear them down.”

Jade Tate ’22 expressed concerns that many students’ activism is performative for social media, which she especially noticed during the anti-racism movement early in the summer.

“It’s hard to decipher who is posting to make themselves look good or who’s posting because they know this is important for the moment,” Tate said. “The most important question to me is, you know, how are you going to take this energy and translate it into the way that you deal with Black people in your everyday life…. it’s just a really tricky space that we’re living in where we can’t even decipher who’s doing this to look good or not.”

Arnaud Gerlus ’22 agrees that a lot of activism at the University is performative and depends on what is trending at the moment, which he also noticed during the summer.

“There’s some people who definitely did post a little list of places to donate and phone numbers to call and have not been heard from since, but that’s another question: does your activism have to be visible?” Gerlus said. “But some people’s [activism] is probably not existent at this point.”

While the University markets itself on its past progressive activism, there is clearly a lively debate among students about if that activism is still largely present and whether the activism that is on campus is genuine or performative. Alongside progressive moments in the University’s history, there have also been many instances of racism and sexism that have reflected the dynamics of the country as a whole.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the University’s first Black student, Charles B. Ray, enrolled in 1862. Ray enrolled at the University in 1832.

Olivia Ramseur can be reached at oramseur@wesleyan.edu

Jo Harkless can be reached at jharkless@wesleyan.edu

-

Good article, but