Henry Spiro

Deadpool Isn’t Silly Enough to Satisfy Audiences

Arts & Culture • February 18 • Henry Spiro

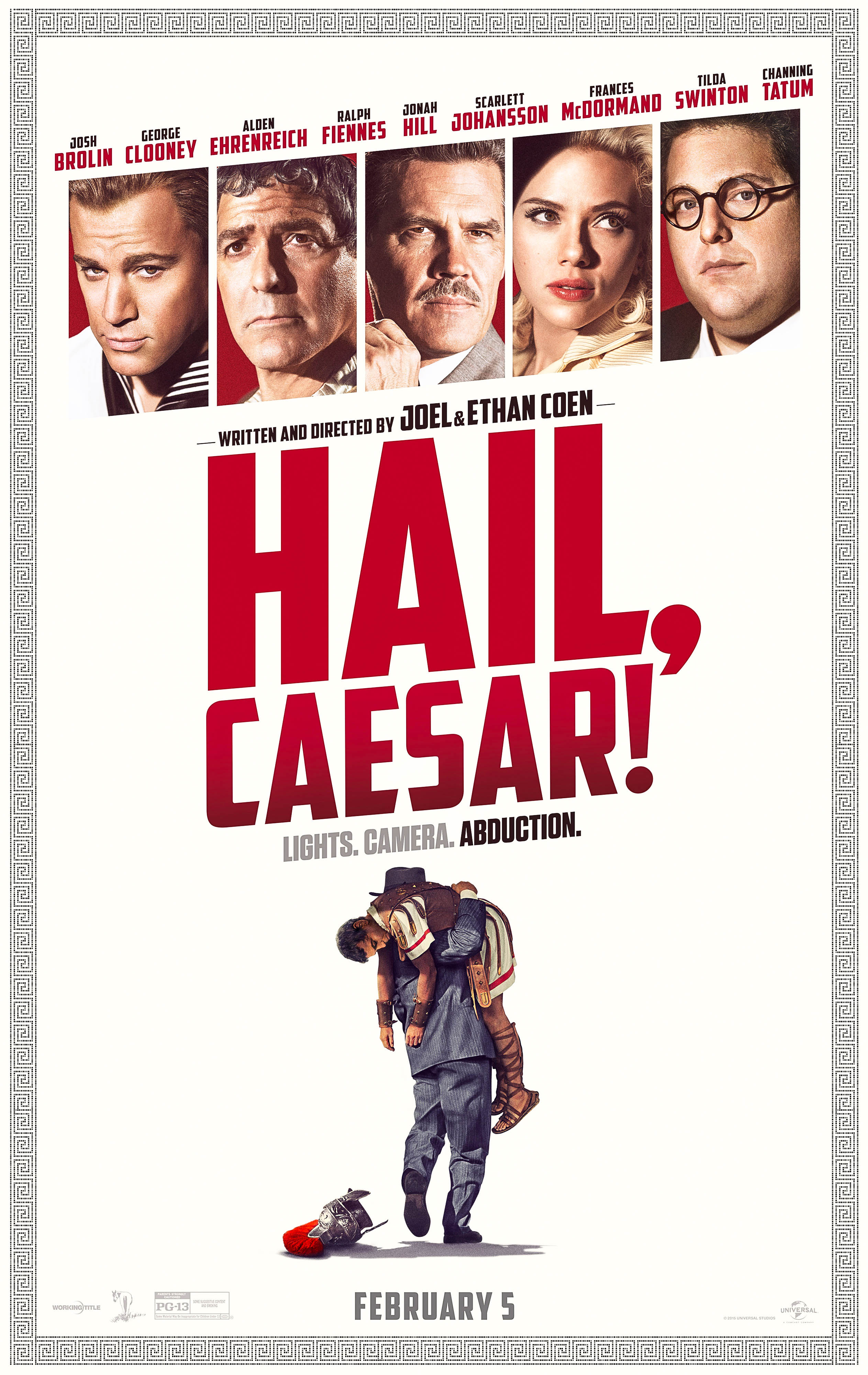

“Hail, Caesar!” Fails its Talented Cast and its Hopeful Audience

Arts & Culture • February 11 • Henry Spiro

In Defense of: Video Games as an Art Form

Arts & Culture • February 1 • Henry Spiro

Big Money, Little Soul: “Star Wars” Goes the Way of “Avatar”

Arts & Culture • January 26 • Henry Spiro