“It’s Chinese autumn.”

“You met me at a very Chinese time in my life.”

These phrases are variations of a meme that has become very popular on American social media. Every time, the punchline is the same: “Chinese.” On the surface, these sentences don’t mean anything, which is why many non-Chinese people find them acceptable to say. To make one thing clear, you probably shouldn’t say you’re “becoming Chinese” if you’re white, even though this has become the fashion.

But though “Chinese” may seem like an empty signifier, it actually does hold significance. That is, a newfound Western interest in, or even bewilderment towards, an emergent global superpower.

The word China or Chinese appears the way a ghost does in a Gothic fiction, an implacable anxiety of something looming on the horizon: the hegemony of China.

The robust online presence of Chinese citizens, as well as American media personalities flocking to the country, has no doubt sparked a new interest in the country’s culture and society. Last year, Twitch streamer IShowSpeed visited China, where he was welcomed by flocks of fans. (There he has earned the popular nickname Jia Kang Ge (甲亢哥), meaning Hyperthyroid Guy, a reference to his energetic personality and bulging eyes.)

Speed’s experiences joyriding around the country became an internet sensation in both China and the U.S. In his streams, Speed gawked at Chinese technological development and deemed the country to be “on another level.” Chinese media outlets dubbed his visit a “soft power win”; indeed, it gave Americans a candid look into a country so often viewed as a threat to America.

Instagram personalities like Ryan Chen (瑞哥英语, @trumpbyryan) have also helped build the cultural bridge. Chen has been praised for his remarkably accurate impersonation of President Donald Trump, often starting his videos with the byline, “I’m in Chongqing, China,” the city he hails from. He then eats a local dish, his way of introducing Americans to a foreign culture in the only way they will understand—in a Trump voice.

To be sure, literature by (Northeastern) Asian-American writers has been calling attention to this “new Asia” since the end of the 20th century. The technological leaps of the Pacific Rim can inspire awe, exhilaration, or terror, depending on who you ask. In “Science Fictionality,” his book on Asian-American fiction, literary critic Christopher Fan calls this the indescribable feeling of being from China, Japan, Singapore, etc., and gazing back at your homeland only to see a stranger.

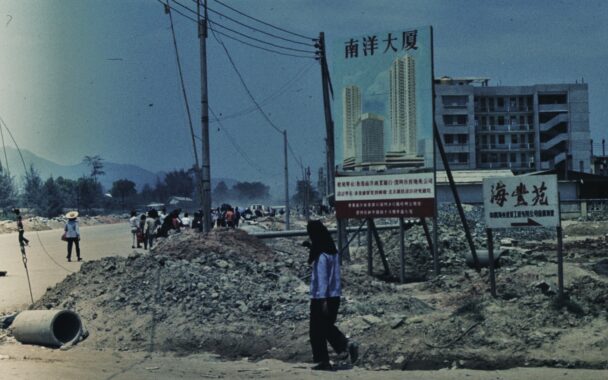

In Amy Tan’s 1989 novel “The Joy Luck Club,” Jing-Mei Woo, the protagonist, is the American-born daughter of a Chinese immigrant. At the end of the novel, she visits China for the first time, and she undergoes a strange transformation. In her own words, she “becomes Chinese.” She can’t help but notice “the skin on [her] forehead tingling, [her] blood rushing through a new course.” She begins to develop “a syndrome, a cluster of telltale Chinese behaviors” like “haggling with store owners [and] pecking her mouth with a toothpick in public…” It is no wonder that these feelings come about when Jing-Mei enters Shenzhen, a city that has undergone a dizzying transformation in the 1980s from a tiny village of 30,000 to one of the world’s largest hubs for manufacturing, technology, and finance.

Speaking for myself as a young person, there is certainly an element of fascination and, frankly, envy in seeing images of China’s high-speed rail, breathtaking skylines, and bustling public scenes. There is an inescapable feeling that preceding American generations left us the scraps, when better things are clearly possible.

Though, as comments on these sorts of videos have pointed out, the GDP per capita in China is still much lower than in the United States. The flowers of modern China were watered by the sweat and blood of laborers working in dangerous conditions for substandard wages, producing goods for global consumers. Still, China’s war on poverty is tremendous, and arguably unrivaled in history. From 1990 to 2020, the rate of poverty in China (defined by the World Bank as people living on $3 per day or less) fell from around 80%—about 900 million people—to zero. In the United States, it increased from 0.5% to 1.25% over the same period. Four million Americans continue to live on $3 a day.

Moreover, the authoritarian activity we commonly attribute to China, like abducting people off the streets, is being carried out by the Trump administration right before our eyes.

In recent years, policy institutes have also levied contentious claims of genocide against the Communist Party of China, citing the construction of special re-education camps in Xinjiang for erasing ethnic identity.

Ironically, every administration from Obama to Trump II has carried out the very same policy, with covert immigration detention centers dotting the U.S. border. The difference is that these centers are a well-documented fact.

If we use China hawk logic, the United States is committing grave human rights violations, and it should be toppled.

No doubt, China has much improved its image in Western eyes in the last five years. An Oct. 2025 report from the Chicago Council of Global Affairs found that the average feeling towards China across all Americans was 35% positive. That was the highest result since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, and a sharp increase from just 24% in August 2024. Also, whereas 58% of Americans in 2023 viewed China as a threat to the United States, now only 50% do, a decline that has occurred across all partisan affiliations.

Despite the unspeakable hate crimes that resulted from the pandemic and the great share of blame China received for its outbreak, China’s response to COVID-19 was a major victory. This meticulous response meant the country of 1.4 billion reported five million infections and 100,000 deaths by the end of the pandemic.

In the United States, by contrast, the pandemic response was disastrous. State and federal power repeatedly clashed as some states allowed lenient regulations, while others did not. Washington, D.C. found itself up against a wall trying to find a middle ground. The one-time “stimulus check” for $1,200, which was followed by paltry economic measures to help the American people, was nothing short of a national embarrassment.

To top it all off, in the world’s most resource-abundant country, which was practically first in line to receive the vaccine, misinformation from right-wing channels convinced a good portion of the populace not to immunize, causing scores of unnecessary deaths. The haphazard COVID-19 response was just one piece of evidence that U.S. power was cracking up.

It should be noted that there is also a pervasive element of Orientalism in journalistic sentiments of the Chinese government. In his book “Orientalism,” Edward Said summarizes common stereotypes of the Oriental: they are “inveterate liars, they are ‘lethargic and suspicious,’ and in everything oppose the clarity, directness, and nobility of the Anglo-Saxon race.”

The stereotype of the Orient is of a mysterious, backwards land that needs rational, Western intellect to step in. The common tagline among China hawks, “It’s the government I oppose, not the people,” belies the civilizing mission underneath U.S. criticism of foreign governments. Do these self-proclaimed “China watchers” care about “the people,” or is it simply the profits to be reaped?

Indeed, this is not the first time the United States has used rhetoric of liberation, freedom, and democracy to justify imperialism, not in the interest of the native population, but itself. One need only turn to the United States’ bloodied history of occupation and intervention in the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia for proof of this contradiction. Guantanamo Bay, the illegal abduction of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, and the arrest of former Bolivian president Luis Arce all attest to the persistent evils of colonialism, despite our living in a so-called “post-colonial” world. With the United States’ aggressions in the international sphere becoming more blatant and absurd—Greenland being the latest thrilling episode—I think more and more Americans are waking up to these contradictions.

But what about Hong Kong, or Taiwan? They are false equivalencies. Hong Kong is a part of China—albeit a “special administrative region” (SAR)—and the Republic of China (a.k.a. Taipei) formally agrees with the People’s Republic of China (a.k.a. Beijing) that mainland and island belong to the same nation. They just disagree about which polity controls it. Claims of aggression in the South China Sea are justified, but unlike the United States, the People’s Republic of China has not invaded a foreign country since 1979.

The United States’ recent blunders on the international stage have unraveled the hypocrisy of its foreign policy, revealing “human rights” as a byword for yellow peril and a pretext for imperialism. The anti-China polemic in the United States, persistent racist attitudes, and rampant hate crimes against Chinese people during the COVID-19 pandemic have left a scar on the Asian-American community nationwide. Call it admiration or fetishism, online memes about China reflect evolving attitudes about the country in light of its economic and cultural ascendance.

Conrad Lewis is a member of the class of 2026 and can be reached at cglewis@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply