Movie Review: “Lakeview Terrace”

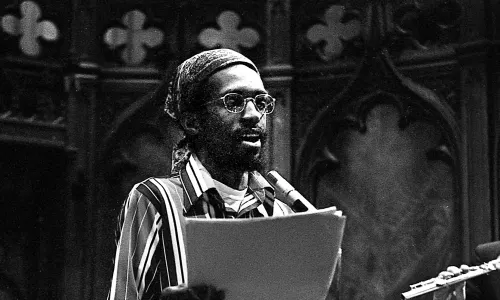

Whatever you think about the quality of his roles, it’s impossible to deny that Samuel L. Jackson has a lot of force onscreen; his gaze is intense but steady, his voice strong and deep. Sometimes, his presence is matched by filmmaking of energy and substance, but often it seems as if he’s employed either to lend gravity to elaborate genre exercises (e.g. “Star Wars” episodes I-III) or to provide an easy parody of his own badass image (e.g. “Snakes on a Plane”). What I’ve seen may not be representative of Jackson’s massively eclectic filmography, but it seems to me that for an actor of such power, Jackson stars in surprisingly few “serious” movies. This may be for the best. After all, it’s dangerous to put an actor of Jackson’s masculine magnetism at the center of a somber drama; his iconic force might throw a realistic world off balance. It’s much easier to give him portentous sci-fi dialogue, or to have him shout a lot and modify every other noun with “mothafuckin’.”

“Lakeview Terrace,” the new film directed by Neil LaBute, ignores the possibility of such a problem, and the results are mesmerizing. Jackson plays Abel Turner, a policeman raising two kids alone in the suburbs of Los Angeles. He tries to be caring and responsible, but his love is tough, to say the least, and Jackson’s performance is every bit as fierce and muscular as his heroic action-movie roles. He’s a lonely man, and the film gives us glimpses of his quiet, everyday routine: He folds laundry and waters the lawn with painstaking care. However, Jackson’s smoldering stare and tense physicality communicate repressed potency, and when a newlywed interracial couple, the Mattsons (Patrick Wilson and Kerry Washington), move in next-door, some angry part of him is unleashed. They are very liberal, very nice, and a little smug, and for some reason, Abel feels like making life a little tougher for them. Jackson’s isolated, aging cop rapidly turns downright scary, even before his tactics become violent; when he makes racial wisecracks to the white husband, Chris (Wilson), as if they were all in good fun, there is a flash of deep resentment in his eyes. As the plot thickens, Jackson’s explosive menace and the poignancy of the character he’s playing become increasingly hard to reconcile.

Just as Jackson’s performance blurs the line between powerful movie-villain and relatable human being, the film as a whole is poised uncomfortably between realistic social drama and creepy psychological thriller. This makes it more effective, for me, than a movie like “Crash,” the 2005 movie about Race, Prejudice, Enlightening Encounters, and other Important Things. I realize that “Crash” has received more than its fair share of hating from critics, and it does confront explosive race-related issues with admirable directness. However, the film’s determination to confront these issues head-on results in heavy-handedness. The culturally and ethnically diverse characters are all suspiciously on the level; they discuss their own prejudices in broad, even metaphorical terms.

“On-the-level” does not apply to the characters in “Lakeview Terrace,” especially when they mean well or are just being polite. Abel and Chris seem, at first, to be polar opposites. Abel is a moral and political conservative who believes that coercive discipline is necessary to enforce good conduct; Chris, who works for a supermarket chain called Good (heh), is an idealistic liberal who tries to avoid butting into the affairs of others. Abel loses control and hits people; Chris pops tic-tacs like sedatives and avoids confronting people directly. However, what they share turns out to be equally important: a need to hide their raw, testosterone-fueled aggressive impulses behind self-righteous “positions.” Chris mutters some snarky response to one of Abel’s provocations; Abel, with a smile so wide and bright it makes you lean back, remarks sarcastically on how “liberals” always do that. “That’s what you call irony, right?” he jibes, while, of course, doing the very thing he’s mocking. Another scene reveals a kind of explanatory back-story for Abel’s distrust of interracial couples, a strategy used repeatedly to drum up artificial sympathy in the aforementioned “Crash.” Here, however, the revelation takes place during a tense, guarded conversation between Abel and Chris after which both walk away even more suspicious of each other. A white man and a black man glaring at each other across a table, explaining themselves but getting nowhere: this scene may be less uplifting than “Crash’s” epiphanies, but I think it evokes the psychology of racism more accurately and viscerally.

Of course, as in “Crash,” this unresolved tension builds until it reaches a climax, even incorporating an overly blunt unifying metaphor (a raging, uncontrollable wildfire=RACISM!). This is where the movie may lose some people. The uneasy marriage of thriller plotting and character psychology that propels this build-up sometimes veers dangerously toward camp, as Abel becomes increasingly grotesque and menacing. This trend raises another problem: is the film’s reversal of the broader dynamics of institutional racism (i.e. making a black man the “oppressor” and a white man the “victim”) offensive? The controversial nature of the reversal is certainly intentional, but is manipulative shock value the whole point?

I don’t think so, although that willingness to offend offers some guilty pleasure in comparison to “Crash’s” dull, PC sincerity. Abel’s frustration, though ultimately destructive, is depicted with respect and compassion. We see him belittled by snotty lawyers for his intensity on the job and goaded by displays of entitlement on the part of the Mattsons, most significantly a sexual act in their backyard, which is witnessed by Abel’s children. Perhaps most touching is a very early scene in which Abel’s daughter confides to her brother that she plans to leave home to escape Abel’s strict discipline. Abel is the scary villain, a force of potent masculinity, yet when the movie starts, he has, somehow, already lost.

Leave a Reply