The Hall-Atwater Laboratory building sometimes feels like a maze of windowless hallways. The elevators are hard to locate, and only one of the building’s three entrances has a power-opened door and is fully accessible for wheelchair users. Starting in late 2022 and ending in late 2025, the University will be constructing a new building to replace Hall-Atwater. Its design aims to be physically accessible, make scientific work feel inviting, and create common spaces where all students feel welcome to study.

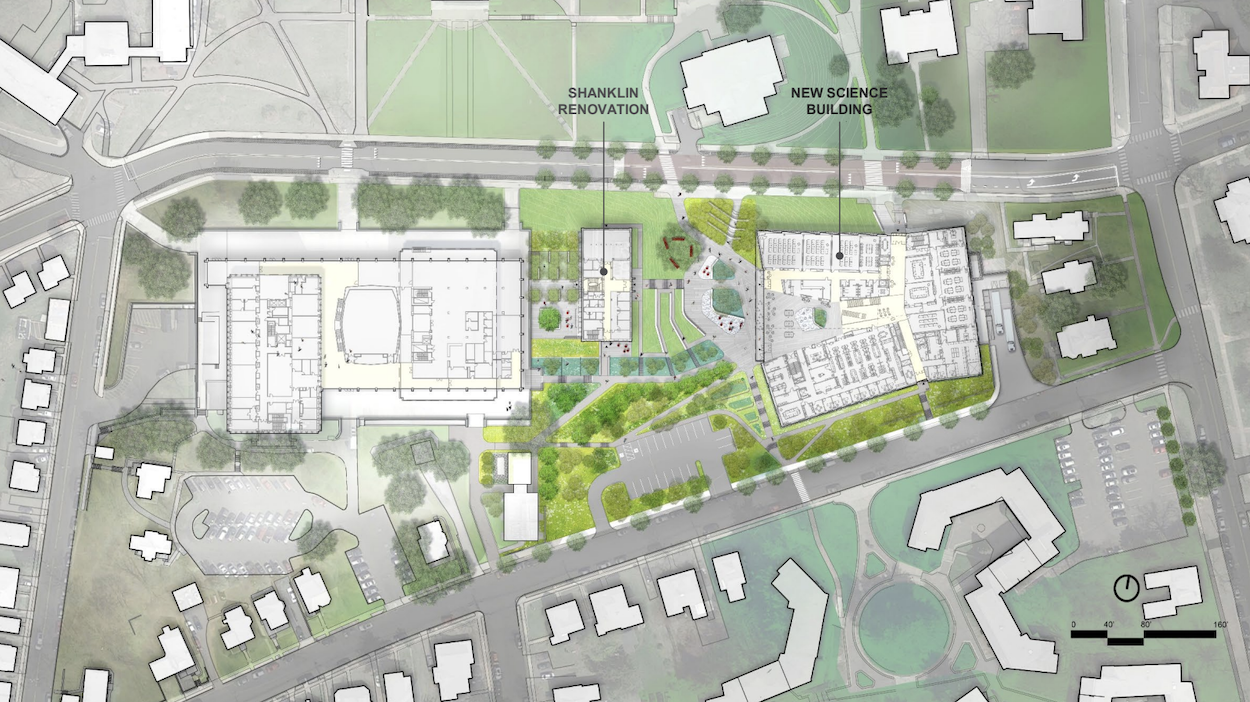

When the new science building is complete, lab equipment will be moved from Hall-Atwater, which will be demolished. Equipment will also be transferred from Shanklin Laboratories, which currently houses many Biology and Molecular Biology & Biochemistry labs. Shanklin will be retired as a wet-lab space, but it will be renovated in 2026 and 2027 to become home to the College of the Environment and the College of Integrative Sciences.

Payette, the architecture firm hired by the University to plan the new science building, met with a committee of students and staff to hear what they wanted in the building and how the design could foster diversity, equity, and inclusion. The committee members emphasized both physical accessibility and the creation of a welcoming environment.

“[People wanted] this sense of invitation,” Payette Principal Mark Oldham said. “Obviously, [they wanted] the reality of invitation, the…lack of barriers to make it easy to move through the project, but there was also the sense that if I wasn’t part of the sciences, I should feel like I’m invited in.”

The new building’s layout will be open, with blocks of lab space on each floor surrounding a central area with seating. Associate Professor of Biology Ruth Johnson contrasted this with the Hall-Atwater building, which has only a few places for students to gather.

“There are these nooks and crannies where I see students gather,” Johnson said. “I love it when you see undergraduates in these little groups, but there aren’t enough of them in Hall-Atwater.”

Labs in Hall-Atwater and Shanklin are in separate rooms, but the new building will have blocks of adjoining labs separated only by sliding glass doors. In addition to wet-lab equipment, the blocks will include a shared “write-up space” where students can sit and work. These spaces will have kitchenettes, marker boards, desks, and other furniture that is easy to move.

Nilukshi Chen ’23 thought the write-up spaces would facilitate collaboration between members of different labs.

“I’m in Professor Johnson’s lab right now, and I never see any [people from other labs],” Chen said. “[I’m] not really talking with them at all, so I don’t know who they are, what they’re working on. I think [the new building’s] spaces are very conducive to that kind of collaboration.”

However, Jessica Luu ’24, who works in Associate Professor of Chemistry Michelle Personick’s lab, was concerned about safety, given that several labs will be accessible through the same locked door and different labs’ chemicals will be stored fairly close together.

“There are some safety concerns over many people having access to the same space, and just having a ton of chemicals in the same space,” Luu said. “I know one of the contractors said it would be easier for people to intervene if there was a chemical accident, but also, there’s still more possibility for accidents.”

The labs are designed to put science and research on display, with glass walls to make the inside of the labs visible from the common areas and hallways. The corridors will also be lined with posters summarizing recent research.

“It has to be a community of science, not a bunch of isolated cells,” Oldham said. “You’ll be able to walk through the building and, just by osmosis, understand [what’s going on].”

The architects originally planned to make the lab walls entirely from clear glass. However, students and faculty said this might feel too exposed, so Payette decided to intersperse the glass with opaque segments. Michael Quinteros ’24 was on a student panel that saw both iterations of the design.

“I was kind of worried at the beginning when they showed that the [lab] wall was entirely made of windows,” Quinteros said. “I think it’s really nice that they listened to the students and reduced the windows on the front side.”

However, Caroline Pitton ’22 thought the visibility of lab spaces might still be hard to adjust to.

“I work in the Office of Admission, and I imagine that once the building is finished, the tour route will go through the building,” Pitton said. “From a sales perspective, it’s really cool to be like…‘There are people doing science, and you can see them,’ but from the student perspective…you’re kind of in a zoo.”

In addition to fostering community, the building is designed to be more accessible for wheelchair users than Hall-Atwater.

“Right now, Hall-Atwater has these physical barriers of steps and stairs and lifts, and it’s very uncomfortable to…somebody in a wheelchair or [with a] mobility challenge,” Oldham said.

All of the new building’s exterior doors will be wheelchair-accessible. While Shanklin currently has no wheelchair-accessible entrances, the renovation will add one on the ground floor.

The principle of universal design—minimizing the need for people with mobility challenges to use separate routes and equipment—has shaped the planning process. Ramps, doors that open automatically, and desks with adjustable heights will be the norm throughout the building.

The architects also said elevators would be visible even at oblique angles from the ends of corridors. They plan to highlight them with materials not used anywhere else in the building. However, Administrative Assistant for Molecular Biology and Biochemistry and the College of Integrative Sciences Anika Dane pointed out that the building’s focal point, a large central staircase, could feel exclusionary for wheelchair users.

“A giant staircase that swirls up the center of the building…that’s very pretty, but if you’re a wheelchair user, you don’t really feel super welcomed by that building,” Dane said. “[They] are building a building for people who walk.”

Students were also disappointed that the new building will not be connected to Exley through an indoor walkway, as Hall-Atwater currently is. The planning team decided that adding a tunnel between the buildings would not be worth its $1.5 million cost. Luu said she often brings samples from Hall-Atwater to the scanning electron microscope in Exley, and walking outdoors to get there could be inconvenient.

Overall, though, the new building is designed to be easier to navigate than Hall-Atwater.

“[Hall-Atwater is] very uncomfortable to the vast majority of users because it’s hard to find your way,” Oldham said. “It’s a rabbit warren. It’s a very inaccessible and uninviting experience.”

The new building’s entire west wall will be made of glass, and the architects hope this source of natural light, visible from most hallways, will help students orient themselves. The wall will have two layers, positioned three feet apart, to provide insulation.

The new building’s digital signage may also make wayfinding easier. Dane said that when office locations change in Hall-Atwater, she has to alter the paper maps that are posted, and she hopes the new building’s electronic signs will be easier to update. Monitors throughout the new science building will also display reservation statuses for conference rooms and seminar rooms to show which spaces are available.

Dean for Academic Advancement Laura Patey mentioned that in addition to improving navigation, the building’s layout could help make test-taking more equitable. Some students need a distraction-reduced environment, so they take exams in smaller spaces while classmates are in a large room. The new building will have small conference rooms located near lecture halls, so students with exam accommodations will have easy access to faculty members during tests.

The restrooms were also designed with inclusivity in mind. After an in-depth discussion with students and faculty, the architects decided to create collective all-gender bathrooms, with single-use restrooms also available for those who are more comfortable with them.

While these features may set the stage for inclusivity and collaboration, Johnson pointed out that what ultimately matters is the way people act.

“In the end, it’s the people who inhabit that building who will then hopefully respond to that environment,” Johnson said. “It’s really then up to the people to make it welcoming or not.”

Kat Struhar contributed reporting.

Anne Kiely can be reached at afkiely@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply