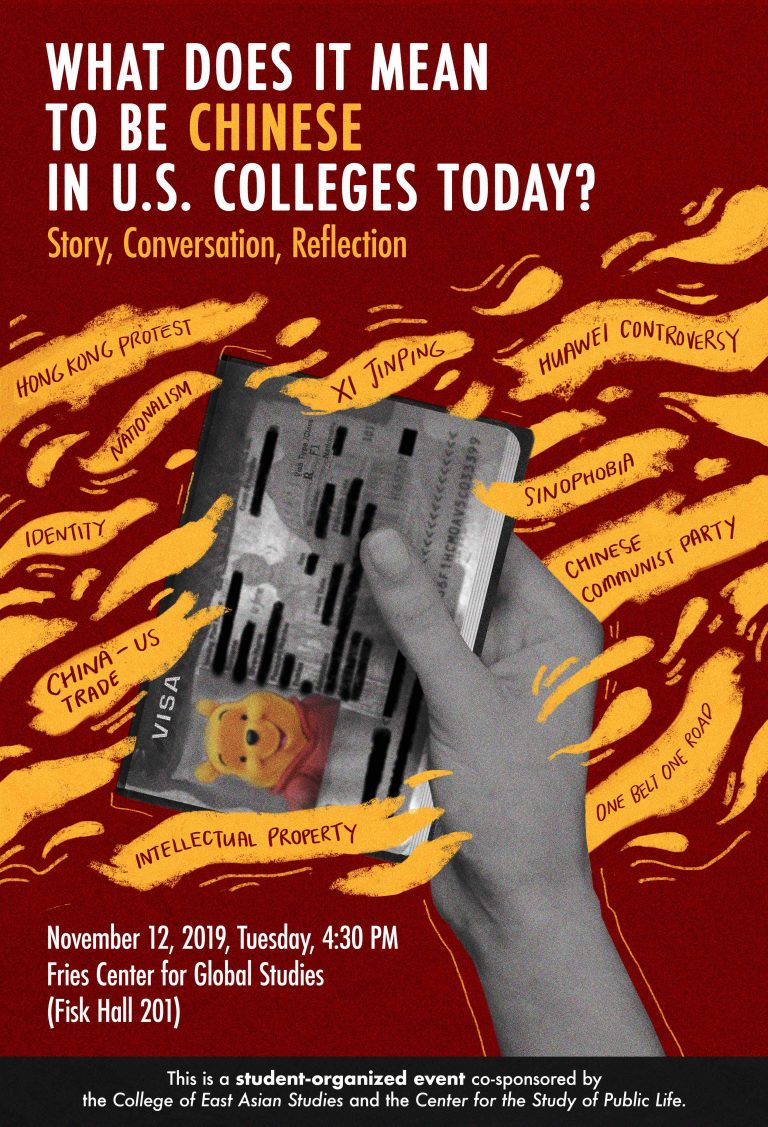

Students from mainland China held a forum on Nov. 12 featuring 14 anonymous stories articulating the diversity of Chinese identities and what it means to navigate college campuses in the United States. The story readings were followed by a discussion, moderated by Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies Yu-ting Huang, during which students had the opportunity to respond to the stories and share their own experiences.

Organizers emphasized that this event was meant to show, through a variety of stories and perspectives, that there is no uniform Chinese identity. Both students and faculty submitted stories that were read by student volunteers seated throughout the audience. Co-sponsored by the College of East Asian Studies (CEAS) and the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life, the forum was held in the Fries Center for Global Studies and drew an audience that filled the room to capacity.

Beginning in June 2019, the ongoing anti-government protests in Hong Kong have sparked global conversations not only about escalating reports of police brutality, the future of Hong Kong, and the reach of the Chinese government, but also about Chinese identity. News of the University’s potential proposed joint-venture campus in China, which has since been abandoned, also contributed to existing tensions on campus. Over the course of the semester, students have engaged with many of these issues through panels, rallies, and discussions between and among different communities.

Haoran Zhang ’20, one of the student organizers from mainland China, envisioned the forum as an opportunity to highlight more student voices from varying perspectives to enrich ongoing campus discussions.

“A goal for us is to foster conversation,” Zhang said. “We think of these stories as a common ground that we can start from and then, you know, facilitate conversation in the future.”

Another forum organizer from mainland China, Yihan Lin ’21, emphasized in an interview following the forum that it was important for the event to be an intimate space where people could feel comfortable expressing vulnerability and sharing their stories without an implicit hierarchical structure.

“Especially when we think of the message we want to convey is that there is a multitude of Chinese identities here and people are struggling with different things, then we shouldn’t have something like a single story being told,” Lin said. “That’s why we kind of had a semicircle format and volunteer readers scattered in the crowd—so that it’s decentralized, so there is no clear hierarchical relationships between the stories. Everybody is equal and everybody is experiencing similar political contexts, but dealing with it differently.”

Another forum organizer from mainland China, Huiqin Hu ’20, drew inspiration for the format of the panel from more informal conversations she and other students had with Hong Kong student organizers the night before the Hong Kong rally on Oct. 11. The rally was held in solidarity with Hong Kong and in opposition to the University’s joint venture proposal.

“I think we reached some kind of common ground partially because, in the setting we had a conversation in that evening, it was very intimate,” Hu said. “Like we were sitting in a circle and we could look into each other’s eyes very closely, so after that evening I was like, ‘Okay, we should have submissions be open to not just mainland Chinese students but also Asian Americans, Hong Kong and Taiwanese students.’”

To address the safety concerns students have voiced about the mainland Chinese government’s crackdown on public dissent through its extensive security apparatus, Chair of the College of East Asian Studies Mary Alice Haddad opened the forum by prohibiting photos, audio, and video recordings.

Following Haddad’s opening remarks, student volunteer readers seated throughout the audience began sharing the anonymous stories. Some stories touched upon the internal difficulties some students face in grappling with questions of Chinese identity, especially amidst the continuing acts of resistance in Hong Kong. Other stories spoke to students’ experiences navigating predominantly white spaces and observing a lack of sensitivity and cultural competency on U.S. campuses.

Speaking to various facets of identity, Lin said that in reality, it is often difficult to separate Chinese identity from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Lin explained that having to interact with the Chinese government in such close proximity and having to operate under it sometimes blurs the lines between national, cultural, and personal identity.

“I didn’t claim authorship to one of the submissions, but one of the submissions read was mine,” Lin said. “What I’m trying to talk about is that, from here we can say, ‘Well, I want to separate the people from the state and from the party.’ But in reality, the people living under this state-controlled government have to deal with the government somehow. At one point, you can just give up your nationality and immigrate. That’s one way. But so long that I think I’m still holding that nationality, it is hard for me to disentangle that.”

One anonymous student who submitted a story to be read also expressed similar difficulties with conceptualizing their Chinese identity as entirely distinct from the political reality in mainland China in an email to The Argus.

“Another reason that it is hard to differentiate these levels of the Chinese identity is the absence of democracy (i.e., people don’t have the power to intervene in the political decision-making process) in China, so that for those who don’t identify with the current political system, there is no alternative ‘China’ that they can identify with,” the anonymous student wrote. “As much as I wish to have a ‘cultural Chinese identity’ to identify with, I personally think that any enunciations of the ‘Chinese culture’ are inextricably linked with the political reality of the time, and to say that there is one homogenous, unchanging ‘Chinese ideal’ is to deny the cultural and ethnic diversity in China, as well as Chinese people’s creativity in interpreting and improving of their traditions over time.”

Nevertheless, the student maintained that it is important to not conflate all of these aspects of identity, as doing so would neglect the agency and efforts of individuals under mainland control who continue to actively resist and denounce the actions of the Chinese government.

“However, I think the effort to distinguish between ‘political,’ ‘national’ and ‘personal’ levels of the ‘Chinese’ identity is still necessary and crucial when we engage in any discourse about China at the present,” the anonymous student wrote. “We need to make these efforts because it is necessary to account for the diversity in viewpoints and experiences among Chinese people, even when the Chinese state denies us such diversity. We need to be aware that the desires for change and resistance still exist.”

Some of the stories were also about facing discrimination and moments of discomfort in academic settings due to feeling targeted because of their Chinese identity.

Huang also echoed these observations by noting the pressures that come with navigating predominantly white spaces.

“I feel like at that point you do feel the pressure of being a representative of some sort,” Huang said. “And I think as the same with any time you are a minority that you can be singled out by belonging to a different group, then you have that pressure of being a representative no matter if you want it or not, so you’re always negotiating with that. Which means that when others see you this way, it’s really hard for an individual to be like, ‘I’m not going to identify like that.’”

The last story was written and shared by Assistant Professor of History and East Asian Studies, Ying Jia Tan. Tan recounted his first border crossing experience visiting Taiwan, which coincided with the 1995 Legislative Yuan elections, months before the first open presidential elections in Taiwan.

“In my Chinese language classes, I had to write essays professing my commitment to state policies that upheld social order,” Tan’s story read. “I was selected to participate in the Taiwan Immersion Program in December of 1995 precisely because my conformist argumentative essays marked me as an obedient student loyal to my nation…. My 17-year-old self, who had spent all his formative years in a de-facto one-party party-state finally experienced what it was like to live in a Chinese society that held fair and open elections. I was surprised at the diversity of political opinions in my host family. My host family had business connections in mainland China, but ardently supported then-Taipei mayor Chen Shui-bian from the Democratic Progressive Party. The ability for all these diverse and even conflicting points of view to co-exist was really enlightening…. That trip opened up new intellectual horizons and gave me a new vocabulary to express my identity. I can never forget, for example, the excitement of singing songs in the Taiwanese dialect at the karaoke. It was like tasting forbidden fruit.”

Following the story sharing, Huang moderated a discussion with attendees. She explained that she perceived her role as more of a facilitator rather than attempting to synthesize what was shared in the anonymous stories.

“Before the forum, the organizers actually prepared a list of questions that kind of tap into more specifically the different possible tension points that people might be encountering,” Huang said. “So I had that list of questions, but when the stories were read, it just felt like we’ve heard so much and I just wanted to give people the opportunity to talk to each other…. I was very pleased that people responded to the stories and also eventually started sharing their own stories. I wanted to put the stories at the center of the discussion, so I didn’t want to guide particularly one way or the other or summarize points and move on.”

Discussions brought to light many of the difficulties of articulating identities amid turmoil in Hong Kong, the Muslim internment camps in Xinjiang, and other territories as well as the psychological toll that often comes with navigating these pressures. Organizers expressed that the forum not only aimed to convey the heterogeneity of perspectives, but also the incredible difficulties students continue to grapple with on campus.

With recent developments of police threatening protestors with live ammunition during an escalating standoff at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HKPU) and an evident rise of Sinophobia, concerns over mental health have affected students from Hong Kong, mainland China, and territories facing encroachment from the CCP.

Jonathan Chen ’20, another event organizer from mainland China, spoke to the increasing need for campus health resources to be culturally knowledgeable in order to support students grappling with these issues.

“Although this event is semi-politically related, I think that the issues on campus are also often about individual students’ psychological struggle and psychological trauma,” Chen said. “And in this case, we need more culturally competent, psychological counselors at Davison Health Center to respond to the growing international student population.”

In an email to The Argus, Director of Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) Jennifer D’Andrea noted that international students constituted 14 percent of the overall cases last academic year. International students make up 10.1 percent of the student body population.

“This semester, we have had multiple students come in for services because they have been affected by the situation unfolding in Hong Kong and Mainland China,” D’Andrea wrote in an email to The Argus. “I think the CAPS clinicians are doing a great job providing support to students as they manage the stressors of day to day life at Wesleyan while at the same time carrying the emotional weight of what is happening at home. At the same time, we recognize we need to do our own work to increase our knowledge and understanding of this situation as well as the lived experiences of all international students at Wesleyan, and we are very fortunate for our ongoing collaboration with Chia-Ying Pan, the Director of International Student Services.”

Haddad also spoke about the difficulties and safety concerns students face by engaging publicly with these issues.

“It’s been a journey,” Haddad said. “I actually think we’re in a much better place than we were at the beginning of the semester as a whole community. But it has been really hard. I am deeply, personally troubled by the fact that there are students on our campus who are afraid that even just their presence at the event will be somehow reported back to China and misconstrued in some kind of way that will threaten their family. And this was true before the Hong Kong protests. So this is not just a result of the protests…. Thank God I have not heard of anything happening to a Wesleyan student and their family yet, but we do know for sure that it does happen with students at other campuses in the United States.”

Lin said that she is glad to see students beginning to have vulnerable discussions with one another.

“I mean, I myself feel like I’m so proud that we are actually in this community who can rationally talk to each other, be vulnerable and start a conversation,” Lin said. “And also that there are people who are willing, brave enough to organize. It’s just incredible. It’s something I have never heard of other college campuses doing.”

Recognizing that many of the issues raised in the stories and during the following discussion cannot be resolved fully in the duration of one event, Lin expressed that she hopes to see these discussions continue.

“I don’t think we are aiming for any kind of closure,” Lin said. “We’re not aiming for people to understand us as our entirety, because there is no entirety—that’s what we are trying to show. So I think what we are hoping for with this event is that this is a start of conversation. We want to inspire something, something good, that can be carried on.”

Serena Chow can be reached at sschow@wesleyan.edu.

2 Comments

Will H

Mainland Chinese foreigners studying in the United States are only doing this because they want to save face in front of American people. The truth is Mainland Chinese foreigners in the United States are rude, crude, bad, and evil people; they chose to talk badly about American people when American people are not around them. It is the fake feelings of the Mainland Chinese foreigners in the United States about American people that will ruin their reputation in the United States. Do not trust Mainland Chinese foreigners in the United States.

Smith K

I happen to know some mainland Chinese students you mentioned, and trust me, these fine men and women cannot care less to “save face” in front of xenophobic lowlifes like you. Scram off.