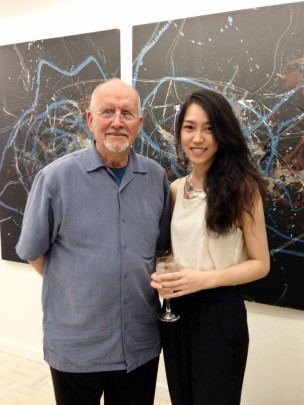

For an art journalist, there may be nothing more exciting and refreshing than interviewing an alumna artist. Aiai Chen ’13, once an East Asian Studies major, has been working at Ethan Cohen Fine Arts, one of the first contemporary Chinese art galleries in New York, since graduation. “Oracle Bone Script Paintings” and “Characters Paintings,” two series of innovative sumi-e paintings under one theme, “Return,” earned her a degree with high honors this past spring. The works are currently on display in the lecture room of the Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies.

Chen agreed to talk about her career path in the art world and her views on the Chinese art scene in the U.S. via Skype this week. The interview was conducted in Mandarin Chinese and translated into English for The Argus.

The Argus: Do you mind telling me something about your background related to Chinese art?

Aiai Chen: I studied Chinese calligraphy with a famous Chinese calligrapher, Mr. Lu Weizhong, ten years ago. It was at Wesleyan that I came to first learn how to paint in water and ink, a very different skill from calligraphy, with Mr. Shinohara Keiji in my sophomore year and continued doing tutorials with him since then.

A: Can you talk about your inspiration for your honor thesis? Any particular mentor, book, or personal experience? How did your ideas about this piece change over time?

AC: Though I got a lot of compliments for my final project for my sumi-e painting class, I was not satisfied at all then. A long time practitioner of Chinese calligraphy, I couldn’t help to think about combining Chinese characters with paintings in an innovative way since then. To me, Chinese characters in any script are art, and thus I began to use merely calligraphy to construct painting, such as a mountain in a landscape. It was actually far harder to do that than [I imagined] because of the very subtle variation of ink and the delicate way blank [space] works in Chinese landscape painting. I nevertheless kept on trying throughout my junior year, and my summer experience at the Tokyo National Museum made my belief in doing creative calligraphy paintings even firmer.

A: It seems interesting to me that you are a sumi-e painter who has a solid background in calligraphy and culture research [relating to] East Asian Studies. Do you want to talk about how your liberal arts experience at Wesleyan shaped your vision concerning your honors project?

AC: I actually didn’t know if my vision about calligraphy paintings [would eventually] work at the beginning. However, I was very determined to do that because of, I guess, an inner urge to delve into the origin of things. I came to Wesleyan with many ambitious goals, but it was the diverse and dynamic campus culture that later pushed me to rethink my artistic and life values. [There were] also many Humanities classes I took at Wes that stimulated me to focus more on the nature of things. You know, to use the tree as an analogy, I was more into the fruit of the tree before, and my Wes experience really successfully trained me to pay attention to the root, the origin and essence of things.

A: What do you mean by the origin of things, and how does this relate to your art making?

AC: In my thesis’ case and even in my current art making, it became an emphasis on the most fundamental part of myself and Chinese classical culture: the very life and the beauty of nature and the world. To me, calligraphy paintings [are] a great way to express those because of the classical aesthetics in composition, color, characters, and also realm. This aesthetics on a visual beauty is quite different from that of other contemporary Chinese and Western art, which values much more the concept and sort of grotesque creativity and beauty.

I would also thank [Adjunct Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies and Anthropology Patrick] Dowdey’s Contemporary Chinese Art class, where I was inspired by so many great artworks he showed in class. In this sense, I would say my Wes experience made me able to appreciate some overarching values and techniques from different artworks. I’m saying the origin of things because I am with growing certainty that our outward appearance springs from our heart. “Return”, in this sense, I guess is to delve more deeply into my heart.

A: That said, how has your work experience at a gallery full of contemporary Chinese and Western art been influencing you? Any expectations for either yourself or the Chinese art scene in general?

AC: I have some mixed feelings about my life now. On the one hand, I did learn a lot from the artists, the colleagues, and the clients I have encountered everyday, and I indeed feel very lucky to be exposed to many great, varied exhibitions here in New York City. They gave me many inspirations for my own Chinese art making. Yet, surrounded by so many new things to learn, such as art business and Western art, while continuing to be an artist among many peers who are working in more mainstream industries where people focus more on practical aspects, I can feel constant pressure, stimulation, and, of course, motivation. When surrounded by so many different voices, I kind of felt lost at first. It was hard to decide my priorities when too many ideas, including some practical pursuits, came into my mind.

I do miss my life at Wesleyan sometimes, when the pace was not this crazy and I had more time to explore freely and wildly. Right now, however, instead of some uncertainty and even solitude I now and then feel about my own vision of doing Chinese art, I am determined to insist on exploring my expected kind of art and career. There is really nothing more important than following my heart right now.

Leave a Reply