This Saturday is Valentine’s Day, and even though the University offers 47 majors, 32 minors, and 2 certificates, no one seems to have an answer to the question: How can one become an expert in the field of love?

This Valentine’s Day, professors from the Mathematics, Art, and English departments translate love, romance, and dating into mathematical, artistic, and literary terms to answer your deepest questions.

What is an analogy for love in your department?

Associate Professor in the Department of Mathematics Felipe Ramírez offers the analogy of a binary relation in the study of discrete mathematics as a comparison to real-life companionships.

“We don’t usually think about [love] in connection with math, but there are analogies,” Ramírez said.

A binary relation describes the relationship between pairs of objects in a set, and certain relations can have different properties associated with them.

“You know the less than symbol, right?” Ramírez said. “One is less than two. So that less than symbol is a relation on numbers.”

The relation is not symmetric because one is less than two, but saying this the other way around would be false. Two is not less than one. Ramírez applies the concept of symmetric binary to a relationship between lovers.

“Importantly, there’s the symmetry,” Ramirez said. “If Bob loves Alice, does that mean that Alice loves Bob? So maybe, for a successful Valentine’s Day, the relationship would be symmetric.”

There are many sorts of relations with a wide range of properties, like symmetric, transitive, and reflexive. The most well-known relationship that contains transitive properties is the equal sign between numbers and objects. If A = B, we could also have written B = A.

The transitive relationship is one where A = B and B = C, thus A = C. Ramírez applies a transitive relationship to personal relationships, asking, “If Bob loves Alice, and Alice loves Fido, does that mean that Bob loves Fido?”

Believe it or not, math can be used to decode love. In a symmetric relationship, your love might be equal to your partner’s love, but unfortunately, in the real world, it does not always end up this way.

“Sometimes Bob can love Alice, and maybe Alice doesn’t love Bob,” Ramírez said. “If I’m to make a parallel to Valentine’s Day, I would say that for a successful one, we should hope to be in a symmetric situation.”

Julia Randall is an Associate Professor of Art at the University, teaching “Drawing I” (ARST131) and “Drawing II” (ARST332). Randall’s birthday is on Valentine’s Day, so her relationship with the holiday is complicated. However, the ideals associated with the Hallmark holiday of Valentine’s connect a lot to the ideas of art.

“I mean, those things are, like, hand in glove, babe,” Randall said.

Randall describes love and art together. Both love and committing to make art require a leap of faith.

“There’s this moment of a suspension of disbelief,” Randall said. “I think love is exactly like that, because you know—you’re not inside that other person, you don’t know what they think, you don’t know what they feel.”

For Randall, this involves a lot of self-revelation. Similar to love, devoting time to art requires commitment, mess, effort, and a whole lot of vulnerability.

How can your field help understand love?

For Ramírez, problem solving has never been about formulas. He describes solving puzzles as applying mathematical intuition to translate what is in his head into a solution.

“If I had to write down a paper explaining what is going on in this particular puzzle, then I would be working to translate whatever I had managed to understand inside me,” Ramírez said. “I translate it into language, into words, and into the vocabulary that mathematicians have developed over time.”

Ramírez describes the way he thinks about math as similar to how poets translate their feelings into their poetry.

“Just like love, just like poems, where it’s not, you know, the poem itself is not the emotion, but it’s trying to convey it,” Ramírez said.

Stephanie Weiner is a Professor of English with a focus on teaching 19th-century British literature. She explains how poetry allows the writer to express their feelings. The lines leave the space for the reader to draw their own meaning.

“I think that, like, in the poetry or song realm, the spareness of it leaves a lot of space for you to enter in and fill it up with your own feeling,” Weiner said. “This is equally true of heartbreak [poetry].”

Assistant Professor of English Sierra Eckert specializes in 19th-century British and Anglophone literature, disciplinary history, critical and social theory, and the digital humanities.

Eckert’s hot take is that we can not understand courtship, what a relationship is, and the tropes that we associate with love today without first understanding how the novel has shaped our ideas of romance. The books “Modern Love” and “Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel” explain how novels have given us these narratives. The novel gave us the technology to think about the public self versus the private self, which we slot into our understandings of what a relationship looks like with narratives of pining and yearning.

In a broader sense, poetry and literature are great mediums for expressing feelings.

“The way in which we experience any kind of emotion, [including love], as a subject is shaped through language,” Eckert said. “I think to the extent to which you can think carefully about how language shapes and mediates the kind of experiences we can have. The language that we use to understand our own emotions is not just unlike the language that a poem uses to unfold or shape the way we experience characters.”

The novel has grown into an attempt to find a package for something like intimate love. As marriage in common media shifted from being purely an economic proposition, plots of marriage then shifted to include love stories.

Just as a novel tells the story of a relationship, Randall draws parallels of art to a relationship as a process that takes time, effort, and evolution.

“You have to be willing to commit to the process, to see how it starts to evolve,” Randall said.

In teaching, Randall describes how somebody may become protective of a particular part of a drawing, describing a need to let the artwork evolve without holding the artwork back.

“There’s this moment where you have to allow the artwork to tell you what it needs,” Randall said. “So there’s like a back and forth thing between holding and letting go, and I think that’s absolutely the same dynamic in love relationships, because you can’t cling too hard.”

Randall continues the metaphor.

“There are times when it’s really frustrating. There are times where you have no you can’t seem to push through a barrier in a piece or something or you’re feeling very avoidant,” Randall said. “I mean, you could literally pick that language up and put it into a romantic situation.”

Favorite love story, literary couple, or artwork?

The Argus then asked professors in the humanities their favorite literary couple to see if there is something to be learned from famous romantic novels.

“This is such a hard question, but I think I’m gonna go with Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy,” Weiner said. “Because I love their witty banter and how they flirt without realizing they’re flirting. And I think they both bring out the best in each other.”

Whereas in novels like “Wuthering Heights,” Mr. Rochester must become injured and blind for the love plot to work, Weiner prefers the Darcy model. Darcy becomes a better man because of love.

Eckert’s answer is not a fictional story, but a real literary couple: two lovers who wrote together, but published under the single name Michael Field.

“It’s one name because it’s the pseudonym of Catherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, who were lovers who wrote together, and they also wrote poems to each other,” Eckert said.

Randall explains that her favorite artworks related to love are less directly expressive of it.

“The [art] work that speaks to me in the way of love is not literal, like couples kissing, or even erotic [art]work,” Randall said. “Those don’t necessarily get to the core of it. I think the kind of [art]work that speaks to me have to do with vulnerability.”

How do I make art or a poem for my Valentine?

Creating a meaningful Valentine’s Day is easier said than done. We asked experts in the craft relating to artwork and poetry for advice.

Randall explains that the meaning resides in the time and effort it takes to create the artwork. Ultimately, her advice is to think about a gesture behind the artwork.

“What can I give of myself that will actually touch my partner, my parent, [or] my child?” Randall said. “You know, what is something that is not just something that is pre-fabricated?”

Eckert shares her advice.

“If you’re writing love poems, my advice would always be like, go read a bunch of sonnets,” Eckert said. “In part because they’re weird.”

Sonnets are a popular format for love poems with 14 lines and a distinct rhyme scheme that present a relationship between the poetic speaker and the beloved object. Eckert explains that sonnets experiment with how to package something big, amorphous, and strange within a strict form.

Weiner offers a poetry-writing game where you substitute words within your sentences after finishing the poem you wrote.

“Take the nouns and make them verbs, take the objects and make them living things, and take the prepositions and make them different prepositions,” Weiner said. “Play around with that, and then you will inevitably get a great poem.”

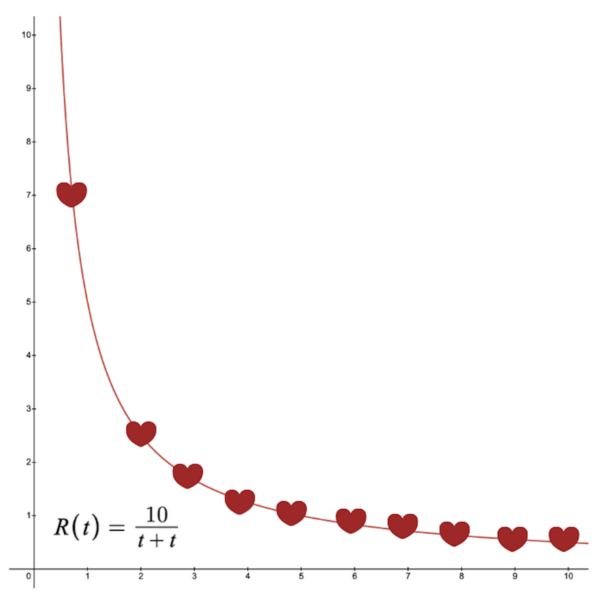

Can you give me a mathematical function related to dating?

Pictured is an estimated average graph, for dating one person, of the number of roses gifted on Valentine’s Day. Time is on the X axis and roses are on the Y axis. Ramírez comments that while he and his wife have been together 16 years, she has always said that she hates receiving flowers. Accordingly, he has never gifted her a bouquet.

“Yeah, so this isn’t universal,” Ramírez said.

Whether or not you are celebrating Valentine’s Day, we hope these professors’ comments will inspire you to go out into the world and express love through math, poetry, or art.

Claire Farina can be reached at cfarina@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply