At the turn of the twentieth century, a new chapter in mental healthcare emerged from the margins of nutritional science. In an age of expanding research and tightening budgets, Professor Wilbur Olin Atwater found his scientific footing in research done in an asylum. This week, the Argives will turn to that page and the questions this chapter continues to raise.

On Jan. 9, 1901, The Argus published an unattributed article entitled “Report of Professor Atwater’s Food Investigations” to commemorate his latest publication.

“An investigation of considerable extent and interest is being conducted by Professor Atwater in connection with the State Commission in Lunacy of New York for the purpose of establishing a uniform or standard dietary for the insane in the hospitals of that state,” The Argus reported. “The second report of this work has just been issued, filling a volume of over 370 pages.”

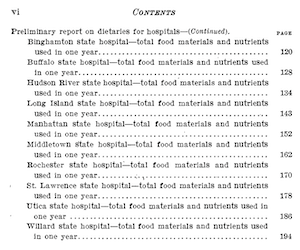

Atwater’s work was published in full on Apr. 10, 1899, in the New York State Commission in Lunacy Tenth Annual Report. Atwater wrote a guide intended to help those outside the field of nutrition science understand the limitations and potential applications of his work.

“The present knowledge of the actual needs of insane hospital patients of different classes is insufficient,” Atwater wrote. “With the insane, as with others, it is important to distinguish between different classes and learn the needs of each class…I think it probable that such inquiry, if properly made, will show that a large proportion of the inmates of ordinary hospitals can be well nourished with much less total food and much less animal food than is now supplied.”

He pushed forward despite lacking complete information, eventually conducting investigations at 10 state hospitals. He devised a tiered asylum feeding system with employees at the top, each following tier receiving smaller daily meals.

“Among the patients who are regarded as incurable, there are, I believe, a considerable number who have more or less exercise,” Atwater advised. “I should suppose that they would be well nourished…The rest would doubtless need less. I should suppose there would be a gradual gradation from this class to those who are almost entirely without activity either mental or physical. The physiological demands of this class would doubtless be very small, scarcely more than…the amount required for maintaining the ordinary physiological activities.”

Atwater believed that asylum patients should not be assumed to function differently from others without cause. The professor feverishly debunked myths about foods causing insanity. Still, his distorted understanding of mental illness mirrored the prominent ideas of the time.

“I think the question may be safely asked whether the administering of food to some classes of insane people is not very much like the feeding of animals,” Atwater wrote. “If this be so, it would be only natural to expect that so long as the food is supplied to them they will eat a great deal more than is really needed. Of course account must be taken of the patients who are disinclined to eat and may be underfed unless they have special care.”

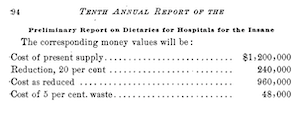

Atwater produced his “Preliminary Report on Dietaries for Hospitals for the Insane” within this framework, which promised the average state hospital up to $240,000 in annual savings (over $9,076,000 today).

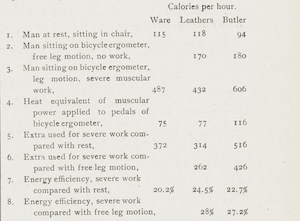

At this point, Atwater was in his 28th year of professorship and the fifth year of human calorimeter experiments at the University. These experiments, conducted almost entirely on Atwater’s students, informed his asylum work. “The Calorimeter Experiment”, an unaccredited article published in The Argus on Jan. 30, 1901, recalled one such study.

“Another series of experiments with the respiration calorimeter has just been completed at Judd Hall,” The Argus described. “The subject was in the respiration chamber for nine days and ten nights…During eight days, he was engaged in very active exercise, riding a bicycle which was attached to a dynamo for measuring the amount of muscular work done…To this end, the diet during four days contained large quantities of carbohydrates, sugar and starch, which, in the last four days, were replaced by fats in fat meat, butter, and the like.”

Muscle work and the utility of nutrients were hot topics inflamed by Atwater’s constant stream of findings. The Argus’ candid account of Atwater’s methodology demonstrated his good standing at the University and early twentieth-century research standards.

“Aside from these experiments at Wesleyan, others are being carried on in different places for the study of the general subject of the relation of food to muscular work,” The Argus explained. “Some of these are being made with students in different colleges, including football teams and boat crews…All of these inquiries are made in accordance with a general plan which renders them much more effective than would otherwise be the case.”

Federal and private funding made Atwater’s inquiries possible. On Oct. 7, 1904, The Argus published an unaccredited article entitled “Work at the Calorimeter”, which explained how Atwater secured the cheddar to conduct a costly cheese study.

“So far this fall there have been no experiments with a man inside the box, but they will begin very shortly,” The Argus wrote. “The analyses and computations in the digestibility of American Cheese, which were carried on last year in a long series of experiments under the auspices of the United States Department of Agriculture, are actively in progress…The final touches are also being given to a large report to the Carnegie Institution of Washington, on experiments during fasting.”

In 1911, the US Department of Agriculture published Atwater’s findings with a fitting title: “The Digestibility of Cheese”.

“Each experiment extended over three days. A total of 184 experiments were made and a total of 65 human subjects were used. Many of these subjects were used in only one experiment, but one subject appeared in 14 experiments,” the report read. “The subjects were mostly students of Wesleyan University between the ages of 19 and 32 years…In all the experiments the conditions were alike, and the result of one experiment is strictly comparable with the results of the others.”

Atwater conducted his human calorimeter experiments on healthy students at the University—vital context to understanding the methodological issues of Atwater’s asylum research. Revisiting “Report of Professor Atwater’s Food Investigations” within this broader context casts doubt on The Argus’ enthusiasm.

“Reports of dietary studies of the amounts, chemical composition, and nutritive values of the food materials cooked, served, and eaten are given and some interesting facts are brought out as a result of these studies,” The Argus said of Atwater’s study results. “It is shown that only about two-thirds of the food supplied is eaten.”

Asylums proved to be new environments for Atwater to apply his nutritional expertise. While Atwater was determined to cut down on waste and costs, The Argus assured readers that his team was keeping patients in mind.

“To reduce this waste, to lower the cost by the substitution of cheaper foods for the more expensive, though not more nutritious kinds, and to substitute food better suited to the physiological needs of the patients and employees of the hospitals is the purpose of the investigation,” The Argus concluded.

Atwater’s drastic results were also the topic of the 56th meeting of the American Medico-Psychological Association in late May, 1900.

“I think [the experiments] will surprise you as they surprised me, and even yet I am skeptical,” commented one Dr. Wise after a presentation of Atwater’s work by researcher Dr. Kidder. “Nevertheless, the persons who made them are so reliable that I should not doubt…Professor Atwater, before undertaking this work, was labored with for some time in order to induce him to undertake it. You all know his reputation as a food expert.”

Atwater’s esteem was clearly essential to getting others on board. Dr. Wise then described Atwater’s particular involvement in the project.

“He then made a formal report to the commission that he considered that the hospitals were using about twenty or twenty-five per cent in excess of the actual needs for the classes of patients they were caring for,” Wise said. “Since that time he has properly reduced that estimate.”

Hopefully, Wise’s comment was correct. Wise then discussed the financial impact of Atwater’s dietary advice.

“I trust that this paper of Dr. Kidder’s will be a stimulus for other States to take up this work, and thus make it possible for the insane to have a scientifically constructed dietary, and one that will do away with much of the criticism which obtain in almost every institution,” he wrote.

Atwater connected with scientists and medical professionals like Dr. Kidder and Dr. Wise through his asylum studies. Atwater’s work fascinated scholars globally, making many eager to see his calorimeter. A blurb published in The Argus’ “Around College” section on Apr. 11, 1906, detailed a special visit.

“Last Saturday Dr. Otto Folin, chemist and physiologist at the McLean Hospital for the Insane at Waverley, Mass., paid a visit to Wesleyan,” The Argus described. “At this meeting Dr. Diefendorf of the Connecticut Insane Asylum and V. C. Myers, Wesleyan, ’05, were also present…Dr. Folin was very deeply interested in the respiration calorimeter and the nutrition work of Professor Atwater, and…the Cryogenic Laboratory.”

Even Corn Flakes pioneer and infamous eugenicist Dr. John Harvey Kellogg spent an afternoon inside the calorie contraption. The Argus briefly reported his trip in its “Around College” section on Apr. 25, 1906.

“Dr. Kellogg, a prominent vegetarian connected with Battle Creek Sanitarium, visited the Experiment Station last week and spent several hours in the Calorimeter,” The Argus wrote.

To The Argus’ modern reader, these “Around College” stories form a collage that reflects the difficulty of determining Atwater’s actions and intentions in the insane asylum chronicles. While Atwater was a prolific writer and left no shortage of documents, the silences and gaps present in the stories available warrant a new inspection of their narratives.

Hope Smith can be reached at hn*****@******an.edu

“From the Argives” is a column that explores The Argus’ archives (Argives) and any interesting, topical, poignant, or comical stories that have been published in the past. Given The Argus’ long history on campus and the ever-shifting viewpoints of its student body, the material, subject matter, and perspectives expressed in the archived article may be insensitive or outdated, and do not reflect the views of any current member of The Argus. If you have any questions about the original article or its publication, please contact Archivists Lara Anlar at la****@******an.edu, Hope Smith at hn*****@******an.edu, and Maggie Smith at ms*****@******an.edu.

Leave a Reply