Have the values of students at the University changed since the ’70s? What did the job market look like back then? As students today are entangled in the constant fight to secure a job after graduation or find a summer internship that looks good on their resume, this week’s Argives columnists, Lara Anlar ’28 and Amelia Haas ’28, have decided to go backward 50 years and see if students of the past were struggling with the same problems of today.

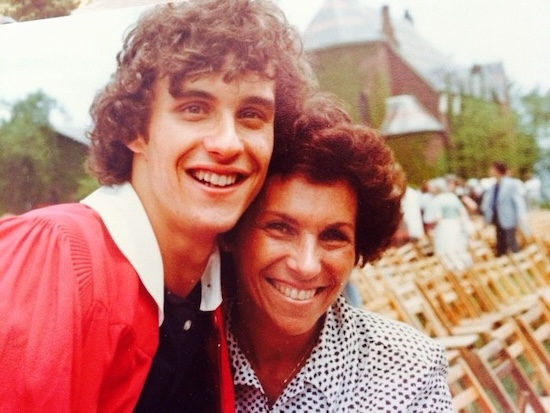

We thought there would be no better person to answer these questions than President Michael Roth ’78, who has compared the job market from his time studying at the University to nowadays in previous issues of the Argus.

On Nov. 6, 2007, The Argus reported on Roth’s inauguration in an article titled, “Roth takes the reins,” by then-Executive Editor Hilary Moss ’08. In his inauguration address, Roth commented on the values of the students and the learning environment he encountered.

“The first thing that struck me when I visited the Wesleyan campus 33 years ago was the exuberance of learning that went on here,” reflected Roth. “[…] And one of the main reasons I’ve return to campus is to work with my colleagues to enhance it for future generations of students.”

He cites the “exuberance of learning” as a defining feature of the University, but we wonder how that excitement has fluctuated over the years. It’s possible that in the present, the fight to get a job may overrule students’ desires to just learn. This may contribute to the overall values that Wesleyan students have regarding what they want to get out of their college experience.

“As I recall, Wesleyan students were much more engaged in current affairs in the 1970s,” Roth wrote in an email to The Argus.

Two years before Roth began his studies at the University, the job market that students were entering looked far different than it does at the present. The dire state of post-graduate opportunities pushed the administration to launch a program to better help match college students with potential job opportunities among alumni.

In an article titled “Administration Joint Effort Helps Students Find Jobs,” written by an unnamed author on Feb. 22, 1972, The Argus explained how the organization aimed to support undergraduates.

“Since, in recent years, the job market has been especially poor for the undergraduate […] [members of the administration] were spurred to initiate this plan,” the article reads. “[…] Not only will such a program provide valuable financial opportunities to students, but it will increase alumni-students relations.”

Besides developing a professional alumni network, the new program researched and catalogued the career outcomes of the University’s recent graduates.

“A random look at the job opportunities that the alumni had made available to students uncovered positions as a truck driver, an assistant director of graduate studies internship at Baylor College, a construction worker, a summer camp grounds helper, a worker at a UConn health center, a yacht club assistant and workers for Kodak in Rochester,” the article reads.

These examples reflect a wide variety of socially acceptable jobs for students at the University to take on after graduation. While getting a prestigious job after college seems more important today than 50 years ago, Roth believes that today’s focus on pre-professional development at universities may be self-defeating.

“These conditions — the consumer mentality of students and their families, the efforts of administrators to provide a full spa experience and the rush of faculty to escape from the classroom into esoteric research — make real teachers an endangered species in the academic ecosystem,” wrote Roth in the New York Times article “How Four Years Can (and Should) Transform You,” a review of Mark Edmundson’s Novel “Why Teach? In Defense of a Real Education,” on Aug. 20, 2013.

Alongside shifts in values and career prospects, Roth cites the impact of students’ diminishing work ethic on the hyper-competitive job markets of today. He suggests that an unspoken rule between students and teachers may undermine both their academic and professional development.

“[Edmunson] knows the studies showing that students spend less time than ever on their classwork, and he writes of an implicit pact between undergraduates and professors in which teachers give high grades and thin assignments, and students reward them with positive evaluations,” Roth wrote.

Roth’s proposed dynamic reflects the heightened pressure that today’s students and professors wrestle with. It appears that 50 years prior, immediately following Roth’s graduation, the stress of both parties seemed generally manageable, allowing a greater number of students and faculty at the University to work with integrity.

Lara Anlar can be reached at lanlar@wesleyan.edu

Amelia Haas can be reached at ahaas@wesleyan.edu

Leave a Reply