This article discusses themes of sexual and domestic violence.

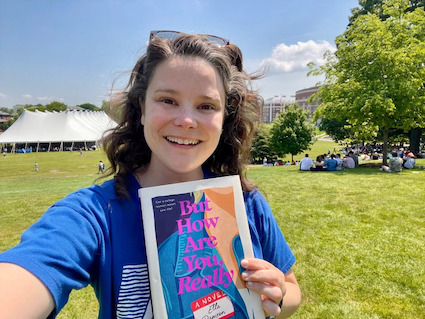

Ella Dawson ’14 published her debut novel, “But How Are You, Really,” on June 4, 2024, a second chance romance set during a university’s five-year reunion. Charlotte Thorne, the novel’s protagonist, works for a tech journalist who has been invited to give the commencement speech at her alma mater, turning her reunion into a work weekend. Starring a bisexual, burnt out artist, “But How Are You, Really” follows Charlotte as she spends time with old friends and runs into both her failed senior year situationship and her abusive ex-boyfriend.

Dawson was a Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (FGSS) major during her time at Wesleyan, concentrating on feminist media literacy and criticism. She also was the Editor-in-Chief of Unlocked Magazine, an art and sexuality publication. The Argus sat down with Dawson to learn more about her undergraduate years, her experiences working in social media and communications post-grad, and her new book.

The Argus: To start off, tell me about your time at Wesleyan. How do you feel like it influenced the path you took after graduation?

Ella Dawson: I feel like I had a very uniquely Wesleyan education experience. My thesis was on feminist erotica as an art form and an activist form of expression. I wrote a bunch of short stories that took place mostly on a fictional college campus about hookup culture and sexuality and desire and what that looked like for women.

At the time, I wasn’t super aware of my queerness, so [they were] pretty straight, but I remember my thesis advisor, Professor [of Psychology Robert] Steele, said that it was “hetero,” but not “heteronormative,” which I just cherished. The theme of my Wesleyan experience was navigating desire and art and making a lot of mistakes and learning how political and social systems and norms shaped our experience.

A: At the time, did you know you wanted to become an author?

ED: I actually never took any official creative writing classes, but I did take a student-run seminar that was a creative writing class about trauma. A friend of mine was teaching it, and it wound up being one of the best resources. I think [the class] was all women and trans students, in retrospect, writing about incredibly intense topics and giving really good workshop feedback.

Weirdly, the foundation of a lot of my future writing happened when I graduated Wesleyan. I had an internship lined up with a feminist independent publishing house called Cleis Press, and they were the foremost queer feminist erotica publishing house in the world. It was a really amazing summer, and I got to know a lot of amazing writers and learned about the genre. Unfortunately, that publishing house was really struggling financially, and so I wound up working in social media instead. Writing was something that I did because I loved it, not because I thought it would be a career. And I just got lucky that I started to write about relationships and sexual health on a little WordPress blog at a time where Twitter was really the center of so much conversation with writers, and I was able to build a platform for myself writing on the train on my way to and from work and becoming like a weird Twitter celebrity in the 2010s internet world.

A: Having a job in social media during that time of utter transformation must have been really interesting. What was it like being in that environment and also constantly creating at the same time?

ED: I had basically two careers running parallel. For my day job, I worked in social media strategy for media companies and nonprofits. I worked with some fascinating people, but also working in social media in the 2010s was so chaotic. The industry changed so much that I wound up learning how to write video scripts and live-tweet events, and it was just an insane time with the industry in flux, so it was very fun, but also incredibly stressful and led to a lot of burnout. And then after hours, I was developing my platform as a writer by writing on my blog. I had written a lot about sexual health, in particular getting herpes while I was at Wesleyan, and for a while, I was kind of internet famous as that girl with herpes. It’s very weird, but that kind of catapulted my career. That made me attractive, I think, to literary agents who might have not been interested in me before because I didn’t have a creative writing degree, and I wasn’t writing for literary magazines.

Eventually I had to leave working in social media because I was super burnt out, and I had built enough of a following with readers online that I launched a Patreon and had enough to pay rent and for health insurance. I had always loved reading romance novels, and they became my big source of comfort and escapism. When I went to my five-year reunion at Wesleyan, it was such a wild experience. And I was like, this is the perfect premise for a romance novel.

A: There seems to be a lot of resonance between your experience graduating from Wesleyan and working in social media and Charlotte’s, with her terrible job and her terrible boss. What was it like navigating your own history while writing this book?

ED: It was definitely cathartic. When I was working on the first draft of this book, I was processing a lot of burnout from having worked for five years at TED Conferences—a media company that works directly with thought leaders—and I had all of these ethical questions I was grappling with like, do thought leaders actually change anything? Is this an exercise in narcissism and personal brand building? Can we really conquer all these issues like systemic economic inequality through these conferences that cost six, seven, eight thousand dollars to attend?

The next few jobs I had, doing social strategy for different startups, I just at a very basic level had horrible bosses, and it occurred to me that I’ve been in abusive romantic relationships before, and the abuse can take place in any dynamic. There’s an inherent power dynamic between a boss and an employee, and that can create a lot of abusive situations. There’s this implicit belief that, yes, I’m being treated like shit by my boss, but that’s normal in a job. And I definitely wanted to use the book as an opportunity to…process the workplace as a garbage experience, and also redefine what it even means to be happy and successful as the workplace burns and the world is collapsing.

A: Speaking of this critique of capitalism and socioeconomic inequality, how do you feel like your experience at Wesleyan, itself a very socially and economically diverse place, informed the way you wrote Charlotte, who experiences very real moments of financial insecurity, both during her time at Hein University and after?

ED: Wesleyan was the first place where I really began to learn and realize how much I had taken for granted. One of the ways where I began to see economic disparity impacting students was when wealthy students who I knew were perpetrators of harm were able to leverage their family’s resources to protect themselves from consequences. It was just one of those moments where I could see money operating in this weird, dark way, even in a place where we were all supposedly supposed to be on level footing.

[In the book] there’s Ben, Charlotte’s abusive partner in college—his father is on the board of trustees, and he’s super wealthy, and there’s definitely a power dynamic within their relationship. I knew boys and girls like Ben at Wesleyan, who had that invisible extra layer of privilege from money and from being legacy students. It meant a lot to me that the happy ending of this book is not just Charlotte getting her love story, but also finding solidarity financially and financial aid from her friends and her community. Finding ways to make money easier to talk about and take some of the shame out of it is really important for all of us [as we] get through the capitalist nightmare that we live in right now.

A: One aspect of the novel that I loved was the parallel stories of her abusive relationship in college and her abusive workplace. It’s really amazing to see you push the boundaries of what we typically consider a “romance novel” and really grapple with issues like mental health, especially in the face of trauma.

ED: We’re seeing this amazing moment in romance where people are beginning to understand that having a wonderful happy ending and a sweet love story is not incompatible with also being a hot mess who faces different real-world issues. I wanted to write a book that’s about the nostalgia and joy of going back to college and seeing your chosen family and how that can happen at the same time that you’re navigating a mental health crisis and seeing your abuser.

And for Charlotte, what she really needs is for people to see what happened to her, to listen to her, to protect her from Ben when they’re in the same space, and to build a new life. And that’s what healing looks like. Romance in particular is a really fun place to break down those stereotypes, because there’s the comfort of knowing that there will be a guaranteed happy ending at the end, and I think that makes people, readers and authors, feel a little safer navigating these really intense topics, because you can trust that it’s going to be okay at the end.

A: This book also felt very millennial—but in a really fun way. How have you navigated online criticism of your generation and its stereotypes in relation to “But You Are You, Really”?

ED: Because the book takes place in 2018, I knew it would feel dated in a certain way. This is almost like recent historical fiction. I think some readers who are younger think that’s all that millennials know—but no, that was intentional. It is a criticism of the BuzzFeed era of the internet, not a celebration of it. BuzzFeed destroyed so much of how the news functions, along with Facebook and the algorithms that completely rocked our publishing and news industry. But if people want to call me a BuzzFeed-core millennial cringe stereotype, that’s also fine. I’ll take the heat.

A: What’s next for you?

ED: I continue to write on Patreon all the time about sex, about relationships, about mental health, about my publishing process. I have some bonus chapters and scenes too from the book that I had to cut or that I’ve just written for fun since then. The idea for this book was such a random lightning strike. I’m trying to be open to whatever weird thing comes next. But it is kind of like I did the thing I always wanted to do with my life, and now what do I do? I guess I’ll try to keep some house plants alive.

A: They’re always more difficult than you think they are. What would you say to Wesleyan students interested in reading “But How Are You, Really”?

ED: I would say that all similarities to real people and places are coincidental—except this book is absolutely a love letter to WesWings and to Ed and to Wesleyan students, who should hopefully feel right at home reading it. And also, I really hope kids still party on Fountain.

If you or a loved one are experiencing domestic or sexual violence, help can be found through the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-7233.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rose Chen can be reached at rchen@wesleyan.edu.

This article has been edited to correct an error in a character’s name.

Leave a Reply