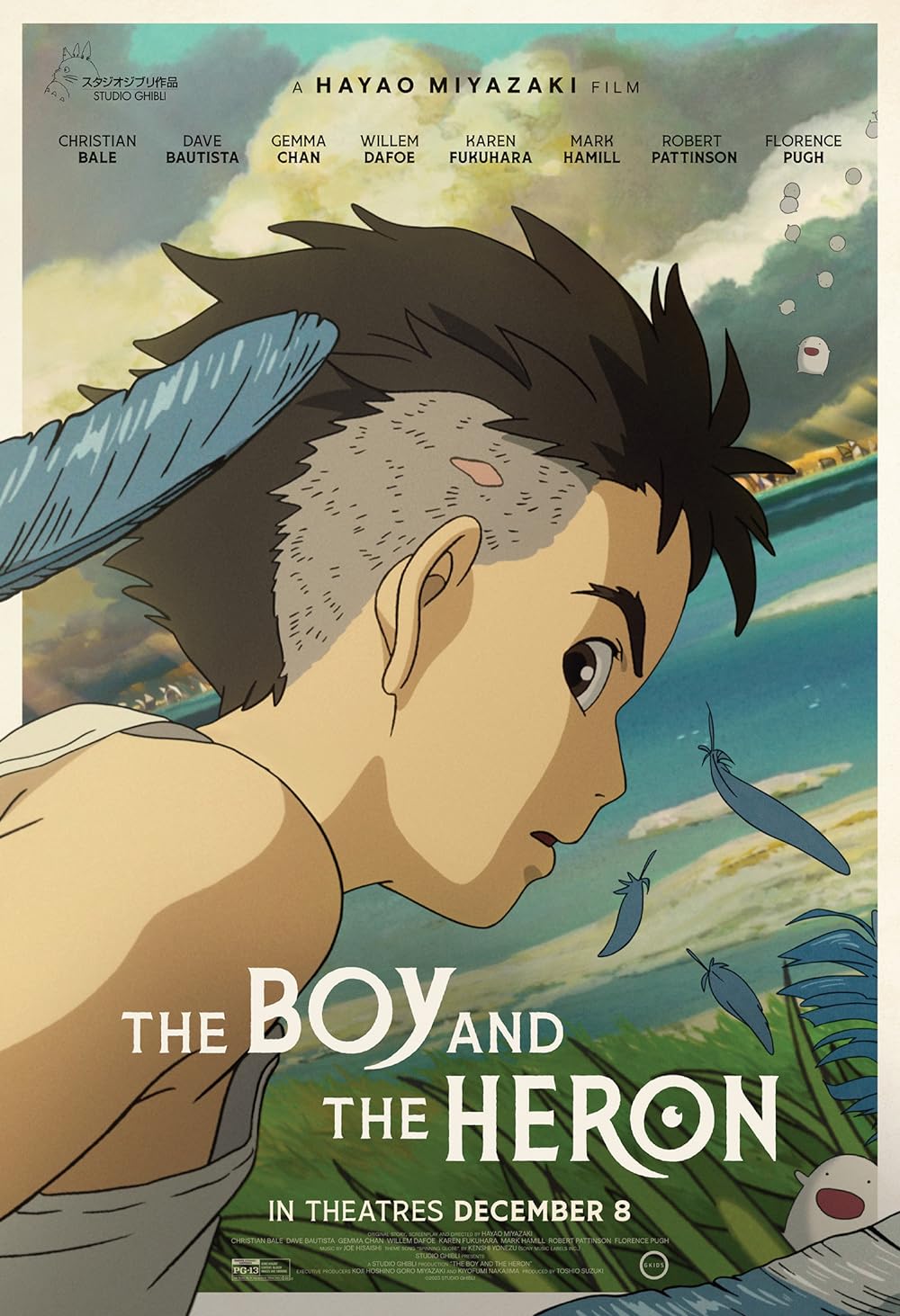

Every young person must eventually learn: Whenever Hayao Miyazaki says he’s retiring, he’s lying. Miyazaki’s last film, the 2013 feature “The Wind Rises,” which examines the life of an aircraft engineer during World War II, was released a decade ago. Now, ten years after announcing his retirement from feature films, Miyazaki and his animation powerhouse Studio Ghibli return with yet another flick set amidst the Second World War. This time, however, we’re following young Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki)—in a return to form for Miyazaki, whose most famous films, like “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988) and “Spirited Away” (2001), have followed child protagonists—as he embarks on a fantastical journey to recover his lost stepmother.

But nothing is as it seems in “The Boy and the Heron.” This unpredictability is another trademark for Miyazaki’s films. The film’s Japanese name is “How Do You Live?”, a title notably shared with Japanese author Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel. The book itself even makes an appearance in the film, as a last memento of sorts from Mahito’s recently deceased mother.

In accordance with this title, uncertainty and mystery take up much of the runtime. Where did Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura)—Mahito’s aunt and soon-to-be stepmother—vanish to? What is the story behind the ominous tower in Mahito’s new backyard? And perhaps most importantly: How is Mahito meant to live in the wake of his mother’s death? You won’t exactly get a straightforward answer to any of these questions. “The Boy and the Heron” is admittedly one of Miyazaki’s denser works. The story and metaphor twine, serpentine, around one another, and neither is especially interested in being easy to parse.

When “The Boy and the Heron” moves from the mundane world to the magical, with Mahito taking the plunge into the mysterious tower in order to search for his missing stepmother, time itself also becomes mysterious. The old become young, especially in the case of Kiriko, one of the elderly maids living on the estate. But, most perplexingly, the dead appear to come back to life; one of the tower’s denizens happens to be Mahito’s dead mother, Hisako (Aimyon), but much younger. Mahito and the viewers learn that circumstances have drawn both him and his mother into the tower’s magical world. Hisako’s great uncle is dying, and because he will soon be unable to keep the tower’s world intact, he intends to pass the duty on to Mahito.

But Mahito refuses. This moment, where he points to his self-inflicted head wound as proof of his inability to make the tower’s world a better, purer place, is where “The Boy and the Heron’s” meaning crystalizes. The film poses a question here: If we, ourselves, are touched by evil—internally or externally—are we capable of making the world a better place? Or will we just reflect that sin outward, regardless of intent?

Miyazaki doesn’t answer this question, like many others in the film. Maybe that’s the point. Miyazaki, who is 82 at the time of writing, is an old man. He lived through World War II. He lived through the bursting of Japan’s bubble economy, the Cold War, and every modern-day upheaval we can think of. Maybe he is telling us—children, adults, and in between—there is no answer to “How did you live your life?”, or perhaps the answer crystallizes only after you die. Even then, the meaning of your life is refracted in many colors, each one unique to each person you knew, and who knew you.

It’s a confusing film. But I think I’ve come to be okay with that. I am writing this after seeing “The Boy and the Heron” for the third time. I saw it two times before—back-to-back, no less—when the Angelika Film Center in New York City was doing a limited early run over Thanksgiving break. And when I first saw “The Boy and the Heron,” I came out of that theater confused and a bit let down. I had been hearing so much about how the film was a masterpiece, maybe even Miyazaki’s best film to date, which is a huge claim. And despite all the accolades and hype, I just hadn’t really understood the film.

Certainly, I’d been aware that there was some huge, philosophical underpinning to the movie. It was a Miyazaki film. And I had heard tidbits of the film’s commentary on grief, childhood, and our ability to internalize them and move forward. But the point was lost on me. Whatever it had been, it had flown straight over my head. Not that that would be a difficult feat, considering my height. But I digress.

I return to “The Boy and the Heron” now, partly because I’ve just seen it for the third time. If you managed to miss it, on Friday, Jan. 26, the Film Series held an early showing of “The Boy and the Heron,” courtesy of our friends at GKids (Studio Ghibli’s American distributor). And maybe there’s merit to the saying “third time’s the charm.” It took me three viewings, but I think I’ve come to both understand “The Boy and the Heron” and made my peace with the parts of it still unknown to me. Maybe subsequent viewings will unveil more. Maybe I’ll even come to hate it entirely. Who knows? But right now, I appreciate the way this film asks me to look at my life and how I’ve lived it so far.

Is this my favorite Miyazaki film? No. That remains “Spirited Away,” because you never really forget your first Ghibli film. But “The Boy and the Heron” is up there.

“The Boy and the Heron” is currently up for awards consideration, most notably a nomination for Best Animated Film at the BAFTAs and Best Animated Feature at the Oscars. It also recently won the Golden Globe for Best Animated Feature Film. Keep an eye out for our awards season coverage as the year progresses. I know I’ll be keeping an eye out to see if “The Boy and the Heron” manages a clean sweep.

Final Rating: 4.5 out of 5 weird gray herons.

Nicole Lee can be reached at nlee@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply