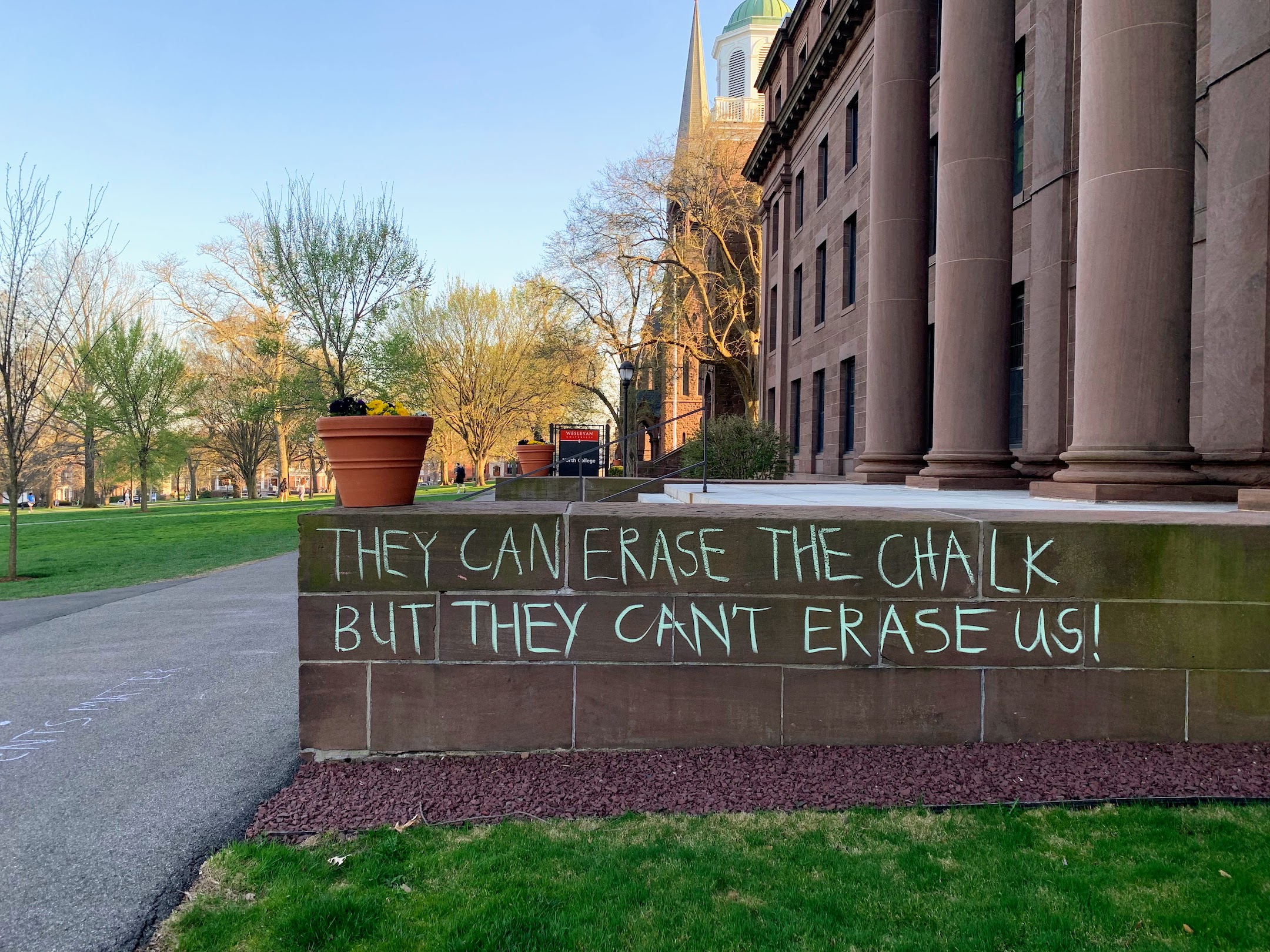

Hundreds of admitted students and their families visited campus to participate in WesFest on Friday, April 14 and Monday, April 17. Along with tours, discussions panels, and activity fairs, visitors were greeted with colorful chalk drawings and statements on the sidewalks, walkways, and walls of the University’s campus. These chalk messages filled heavily trafficked areas of campus, including sidewalk space in front of the Center for the Arts, Olin Memorial Library, and College Row, despite the ban on writing with chalk on University property that has been in place since May 2003.

Many visitors may not have known about the chalking ban, and that students who were chalking during did so at risk of disciplinary action. Since the ban was instituted, the ways in which a public, anonymous form of expression like chalking can be both beneficial and destructive to the community have been a topic of hot debate, and students have engaged in chalking against the rules in both organized and disorganized ways over the last two decades.

The most recent resurgence of chalking started when a group of anonymous students created a shared Google Drive folder with several documents that explain what chalking is, inviting University community members to chalk and suggesting locations, times, and messages for prospective participants. The organizers set each document to be open to public editing, allowing any student to add to the shared information in the documents in an effort to decentralize power in their movement.

In a document titled “Comprehensive Document on Chalking,” the students explained the significance of chalking as a form of collective resistance, gave a short history of the practice of chalking on campus, and called the readers to immediate action. The folder also provided a map that highlighted the possible risks of chalking in different locations on campus.

“You’re reading this because you’ve been stumbling about in the jungle that is Wesleyan organizing, activism, and institutional reform,” the students wrote. “It’s a thick jungle, where voices are often drowned out by the incessant ambient buzzing everywhere. In this file is a plan to reclaim and express those voices. On 4/13, there will be an organized effort to chalk Wesleyan University. This is a call across class years, across student groups, and across faculty and staff to participate in this plan.”

Charissa Lee ’23, one of the students responsible for compiling the documents, took to the streets of campus to chalk messages on the night of Thursday, April 13. She and other students shared messages ranging from idle drawings and puns about chalk to messages about recent controversies and criticism of the administration’s handling of several issues.

“The first place [I chalked]…was right outside of admissions, and I chalked, ‘Are you Wes Brave?’” Lee said. “That was the first thing I chalked, [and then] I chalked ‘Roth, is this safe enough?’ That was at North College.”

The following day, Lee followed tours for admitted students and their families and chalked messages about campus life at each of their stops. She described how, when a tour group she was following stopped in front of the Patricelli ’92 Theater, she added a message about the inactivity of the renowned student-run theater production group, Second Stage. Lee said she felt that chalking during the tours added a layer of performance and emotion to the practice of chalking.

“The intention behind following [tour groups] as they walk was to think about this medium being….evocative and powerful and the way that it can exist in all spaces and bring attention to different things as you confront them,” Lee said. “[They would] look at this building, hearing [one] message [from the tour guide] but seeing [another] message, and what I hope people got out of that was the fact that this institution is a lot more complicit and harmful than [it is] marketed to [seem]. My medium of chalking was to bring awareness to information, but also show that [chalking] was a part of Wesleyan culture that can be used really effectively.”

Another student, who wished to remain anonymous and will be referred to as Student X, used chalking as an opportunity to connect with incoming students during WesFest and provide context of the history of chalking as a form of expression on campus.

“During WesFest, I talked to prefrosh and [gave] them opportunities to chalk on campus, obviously giving [them] the full context of any potential risk,” Student X said. “It was really interesting to see how excited people were to be able to be a part of a community, be building solidarity and be able to [protest] the University in overt ways, even before they’re officially students on campus.”

Lee said she was also impacted significantly by an interaction with a parent who saw her chalking and asked to take a picture that he promised to send to Colorado Senator Michael Bennet ’87, son of President Douglas J. Bennet ’59, who instituted a moratorium on chalking in late 2002.

“[The parent] was like, ‘I’m gonna take a picture of you and send it to [Bennet] and tell him the resistance is real,’” Lee said. “I wanted to chalk that: ‘The resistance is real.’”

The indefinite moratorium on chalking instituted by Bennet in the fall of 2002 was as controversial then as it is today. Bennet sent a campus-wide email prohibiting the use of chalk on University property in response to targeted, sexually explicit chalk messages and drawings that sometimes included racial slurs.

Many students strongly opposed this decision, describing it as a limitation of free speech on campus. This was especially upsetting for LGBTQ students, as Queer Alliance, a campus advocacy group for LGBTQ issues, was known for their regular chalk-in activities.

Students were not the only stakeholders on campus for whom chalking was a contentious issue. The faculty assembly voted 44–8 against the ban, while 53 members of University faculty and librarians signed a letter in support of Bennet’s policy.

The issue sparked such a scandal that The New York Times covered it in an article in November 2002. The article highlighted that the controversy around the decision was heightened by the University’s reputation as a center for social justice and freedom of expression, referring to the University as “the most activist campus in the country” and “Diversity University.”

For many students, their drive for this campaign is born from a sense of dissonance between the Wesleyan they were sold as prospective students and the one they attend. Wesleyan’s legacy of student activism remains intact to this day, especially in its admissions materials, as an element of campus life that distinguishes it from other universities. Another student, who also wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as Student Y, explained that when students arrive on campus, the spirit of social justice that Wesleyan is known for often doesn’t seem to exist.

“What’s so painful is that the University is very aware of this narrative and actively uses it in marketing and branding,” Student Y said. “But, at the same time, when students come here because of that match, [they feel] this dissonance because it’s not there. I think chalking represents a sort of the forwarding of that experimentation.”

This is one of the main reasons why they and other students chose WesFest as a targeted period of chalk protest.

“A lot of Wes students come in because they have the image that this school is justice-oriented, and [that] the curriculum and student life are very motivated by the activist spirit,” Student Y said. “The contradiction is so salient…when you have a university erasing chalk that is often constructive and positive and to react [to it] so extremely. It’s a very strong message to send to admitted students.”

A tour guide in the Office of Admission who wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as Student Z elaborated on the University’s heightened level of visibility during WesFest.

“I would say that [WesFest is] definitely [a time when the Office of Admission] not only has the highest volume of visitors at one time, but there’s a lot of pressure on the school presenting itself as a place [that] is the most ideal college that [a student] should go to,” Student Z said. “There’s a general vibe of…trying to brand Wesleyan [as] funky, fresh and cool, [and] they’re going to make sure that you see some fun bands [and] that you go to the club table and see the artsy clubs we have. At the same time, we want [it] to seem that…the school is also a place for serious scholarship.”

The anonymous tour guide shared that the chalking during WesFest was considered disruptive by some of their superiors in the Office of Admission.

“People were visibly chalking around campus, much to the chagrin of…some of the higher admissions faculty,” Student Z said. “Some people felt like it wasn’t a proper channel to protest or get their message across. What was communicated to me from the admissions department was that [chalkers] were following guests, and when [guests] walk into campus, [they’re] not consenting to be followed and have people who are not in the admissions department be a part of [their] tour experience.”

However, the tour guide shared that they believe that witnessing campus life in real-time, with or without disruptions, is an integral part of the tour experience.

“If you’re on a campus as a visitor, you should expect that there will be people that intersect in your path,” Student Z said. “If you’re in the library you’ll hear people talking to [each other]. If you walk across Foss Hill, there’s gonna be people laying there doing their homework [or] playing Frisbee. You’re going to be part of this ecosystem on campus already.”

Then and now, chalking has proven to grab the attention of students, faculty, administration, and the occasional national newspaper, especially since its restriction. Student Y said they sought to combine visibility of the visual medium with the expanded audience of admitted students and family members during WesFest for the largest possible impact. They emphasized that they see their goals for the current chalking campaign as being aligned with the goals of past University students who chalked.

“We chose [chalking] as a response to [campus issues] mainly because the criticisms that [students] initially were making when chalking was first banned in 2003 are the same [criticisms] that we’re making today,” Student Y said. “They were saying the same things about the administration, thinking that it can treat its constituents as if [they were] not really there. Chalking was always a response to reclaiming that space physically and visually.”

Student X emphasized that the medium of chalking was just as important as the messages they shared, adding that it opens avenues for communication across student, faculty and staff groups that don’t often interact, even with the proliferation of the internet and social media platforms.

“One of the important things [about] chalking is [that] it provides opportunity for people [to have] communal conversations in a way that the internet is presupposed to provide,” Student X said. “[Social media is] self-selecting, and you’re only being fed the things that this algorithm knows that you are interested in, [but] there is no chalk algorithm. You are walking around, and you will invariably see it. It was really interesting to see how we could communicate with different parts of the campus community than we normally could, because there wasn’t any sort of opt-in or opt-out.”

Lee also underscored the significance of chalking as a mode of communication, stating that the medium itself outweighed the content of the messages.

“[Chalking] wasn’t a means to an end,” Lee said. “Yes, we are raising awareness about these issues. But the engagement was the end product and to think about how this medium is a culture in which everyone can engage with, and if it evokes any and all emotion, it has achieved its purpose.”

While Bennet established the chalk ban, Roth is no stranger to addressing the controversy. In a blog post from September 2007, early in his presidency, Roth responded to a chalk message written outside his house about his response to global warming by criticizing the medium, before addressing the question in his post.

“‘Michael Roth, What are you doing about global warming?’” Roth wrote. “These were the words I saw graffitied on the sidewalk near my office this week. There were a few more global warming tags at the Usdan Center and walkways. What an important subject, but what a dumb way to articulate it!”

Roth said he maintains the stance that chalk is a form of graffiti. In a recent interview with The Argus, he explained that this is the primary reason chalking is still banned on campus.

“I have no plans to repeal the ban on campus graffiti,” Roth said. “The ban is agnostic about what people use to make graffiti, and it’s agnostic about content…. The walls of the University and the pavement are places of communal traffic…. From my perspective, it’s not about the content, it’s about not having graffiti on campus, and not having to clean it, which we had to do during WesFest and cost thousands of dollars.”

Lee explained that she is similarly agnostic about the content of her chalking, leveraging her last few weeks as a student at the University to highlight a medium that she believes holds important historical and cultural value on campus.

“The act of chalking is what I wanted to get across, not necessarily the content itself,” Lee said. “So when someone asked me, ‘If they start erasing messages, why don’t we just write it on a T-shirt?…. They can’t strip us,’ it’s like, no, you’re missing the point. The medium is the message.”

On the other hand, Associate Professor in the College of Letters Jesse W. Torgerson highlighted that on other college campuses across the country, limitations placed on chalking are being debated as a free speech issue, rather than one of vandalism and visual eyesores.

“From a beyond-Wesleyan perspective it makes sense that on public university campuses chalking has recently been framed as an issue of free speech and has even been raised as such on venues like Fox News,” Torgerson wrote in an email to The Argus. “My graduate school years were at UC Berkeley—the birthplace of the so-called Free Speech Movement—where chalking (along with large signs and literal soapbox speeches) was and is a constant feature of the campus pavements.”

For Lee and other students, restricting mediums of student expression can be interpreted as restricting the speech itself.

“When Roth says, ‘I really wish that [students] would protest more important things like gun control,’ what he is doing [is] explicitly gatekeeping what activism can look like,” Lee said. “This is how we want to express ourselves [as] activists…. For [Roth] to say that’s not really activism is effectively diminishing our voice and our capacity to be activists in this space.”

Assistant Professor of Earth & Environmental Sciences Raquel Bryant affirmed the importance of student expression in connecting different stakeholders on campus for open discourse about issues that face the University.

“Forms of expression like chalking are core mechanisms for students to be able to voice their opinions about campus life and spark broader discussions around topics that impact everyone in our campus community,” Bryant wrote. “What I admire about chalking as a communication form is that it can be both critical and creative and these are Wesleyan ideals we should embrace when we are considering the value of chalking on campus.”

Student X added that while Roth dismissed the medium of the global warming question in his 2007 blog post, he did ultimately engage with the issue for the duration of the post.

“There’s Roth’s blog post [with] his reactions to finding someone chalking about climate change outside of his [office] and he’s like, ‘This is a dumb way to incite political speech. This is so unhelpful,’” Student X said. “But he proceeds to write an entire blog post responding to the content of the speech, which is a complete objection to his whole thesis that chalking is a silly way to communicate. Obviously, it’s effective, because he’s responding to it.”

In his explanation of why the ban is being upheld, Roth also noted that the original moratorium was established in response to chalk messages that some faculty members felt made their work environment hostile.

“It was President Bennet who instituted [the ban] partly, at the time, I’m told, because some of the chalking was pointed enough or salacious enough to have some employees say [it] created a hostile work environment,” Roth said.

Student Y affirmed that they were shocked by the sexually explicit, targeted, and often racist messages that incited the original moratorium. However, they believe that a repeal of the ban would give the student body the opportunity to demonstrate the progress, conscientiousness, and maturity it has built over the last two decades.

“I think it’s important to know the harms [that] have come with it, but also to believe in the community to keep each other accountable, believe that it is in a better place than it was [10 or 15] years ago, and allow us the opportunity to assert that it is better, and that we can be better, and that we are,” Student Y said.

Going forward, many agree that the time to revive a cross-campus conversation about chalking has arrived. Student X explained that one of their goals while participating in the resurgence of chalking has to do with the lack of information on the history of chalking and other forms of student activism provided by the University.

“I think it starts with an open and honest dialogue [that] would include providing that information and history, providing the context of why staff, faculty, and administration as well as certain students were deeply hurt by the impacts of chalking,” Student X said.

Torgerson affirmed the importance of access to historical knowledge about chalking on campus for understanding its value in the University’s current context.

“A College of Letters student won University Honors in 2004 (before my time!) for a brilliant historical and critical thesis on chalking at Wesleyan,” Torgerson wrote. “Campus records reveal at the time chalking was banned (2003) it was deeply intertwined with student expression, activism, and organizing around queer identities, and was beginning to turn to questions of race. This is a history worth knowing.”

With communication and community building at the center of their goals, Student Y emphasized that the objectives of the chalking campaign were not to alienate the administration from the student body, but to revive discourse about campus culture and activism among all stakeholders.

“It was very important to not antagonize the administration…because all of this is grounded in building community, and reclaiming community,” Student Y said. “We made a very deliberate effort to [build in] safety mechanisms, what content should be said, because that’s part of the reason the university sort of banned it in the first place was that they didn’t see that as a possibility at all.”

Torgerson also acknowledged that, ultimately, Roth’s consistent commitment to open academic discourse aligns with the goals that he’s seen students put forth during this chalking campaign.

“In light of all of this I would personally want to affirm our own president’s strong commitment to protecting ‘speech and expression, even when noxious or offensive’ that also acknowledges the communal responsibility to extend ‘respect and openness of mind’ in discourse,” Torgerson wrote. “A renewed discussion of why or why not chalking is acceptable on this private university campus seems very of the moment (President Roth even used ‘extreme’ free speech as the pretext for his annual April Fool’s post) and so I am proud of our students for caring deeply enough about this national issue to think about how it applies to our own local context.”

In the spirit of reopening campus discourse around chalking, the Wesleyan Student Assembly (WSA) rushed and passed Resolution 13.44 entitled “Let’s Chalk About It: Condemning the Chalk Ban” on Sunday, April 16. WSA President-Elect Orly Meyer ’24 explained the process of rushing a resolution in an interview with The Argus.

“Typically, resolutions are introduced [during] one General Assembly [GA] meeting,” Meyer said. “Senators provide feedback and ask questions. Then during the week, [senators] can also provide more in-depth feedback and make edits to it. At the next week’s meeting, they’re voted on. Rushing the resolution last week required a two-thirds vote of the GA to rush it, which means skipping the week of waiting for edits to vote.”

WSA Academic Affairs Committee Chair Claire Stokes ’25 shared that while the resolution passed, a number of senators chose to abstain from voting, herself included. She expressed her hope that in the future, the WSA will also act as an avenue to bridge the gap between students, faculty, and administration.

“The WSA is here to liaise between the student body and the faculty,” Stokes said. “Recently, people [have] come to us with resolutions that are our indirect disagreement with the faculty, and as someone who works on a faculty-facing committee, I think that [it] can be really hard to make [change] actually happen.”

Meyer underscored the importance of building strong relationships with members of the faculty and administration in order to cooperate on campus issues, even in the face of disagreement.

“Building relationships with faculty, staff, and the administration is an important part of our role,” Meyer said. “It’s still okay for us to say that we disagree with them, because we’re [always] working on building those relationships and working with them in a very cooperative manner…. I feel that the administrators trust us to share the feelings of students. If there’s a disagreement, we can work together and figure that out.”

Lee added that she believes communication must be centered in efforts to use chalking or any other means of activism to open lines of communication among students, faculty, and staff, and that students must be intentional about their activism efforts and cognizant of potential effects.

“I think building culture takes time,” Lee said. “And if the ban does get lifted, the students who are behind the organizing of chalking have to be very intentional [in] bringing this culture back. Allowing students to identify what parts of Wesleyan history they want to revive and keep as a part of their culture is extremely empowering, because you’re giving students agency to decide and redefine, and co-create culture and identity that is relevant to Wesleyan in 2023.”

Bryant also hopes that faculty and other stakeholders on campus will participate in campus expressions and join the conversations students are having about campus culture.

“I’d love to participate in a chalk-a-thon with both students and faculty,” Bryant wrote. “I think we all could use some more exercising of our intergenerational, coalition-building muscles!”

Last October marked the 20th anniversary of Bennet’s initial moratorium on chalking on University property, but the issue has never really disappeared from campus discourse. In The Argus alone, there is evidence of major resurgences on campus in spite of the rules against it, as well as campaigns by student leaders to repeal the ban, about every few years since its establishment (see coverage on the matter from 2007 and 2013). Wesleying also published a series of blog posts titled “WESTROSPECTIVE: A Decade Without Chalking” in 2013 in which writers explored the history of the practice on campus and spoke to people central to the controversy of the initial ban. Many pieces written by students have shown not only support of chalking as a form of student expression, but also critical reflection on the harm to students, faculty, and staff across campus that has been transmitted through some of the messages written over the years.

In the face of the administration’s continued refusal to end the ban on chalking, some students are still optimistic about the future of the medium and hope that if its practice is restored, it will serve as a reflection of the spirit of the student body.

“In the best-case scenario, [chalking] will just be a mirror of who the student body is,” Student Y said. “If we’re brave enough to look at it, it will be such a powerful tool for us to keep pushing for more and more positive change.”

Sulan Bailey can be reached at sabailey@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply