For the first time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the University’s senior studio art majors’ thesis projects took over the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery (Zilkha) last week. While it started as a tentative plan laced with uncertainty, this first week of the Class of 2021’s thesis exhibitions has shown that the University’s indomitable creative community is just as capable as ever of putting on a stunning artistic display. Featuring six artists working in formats from painting, architecture to multimedia, the projects offered an impressive glimpse into some of the arts at the University.

Immediately to my right as I entered the gallery last week, “a line: half metal, half water,” an installation of photographs by Noa Lin ’21, set a tone of materiality expressed through the stillness of landscape and portraiture. From a man staring out on the water while leaning against a wooden and metal barrier to a dramatic, V-like cavity in the coastline, the installation’s subjects appear equally concerned with nature and the structures we’ve built around it.

“A lot of the photographs deal with obstruction, illusion, or boundary in a certain way,” Lin said. “Now, in its final incarnation for this year, I think it revolves around an idea of the coast that is kind of a paradox, like on one hand the coast proposes this infinite recession, this kind of limitlessness and freedom when you look out to the coast to the horizon, and it’s just kind of open and unimpeded, but at the same time, there’s this reality of the coast being this geographic limit and boundary that works against this. I wanted the photographs to play with the idea of the coast as boundless on one hand but all these impositions of fences and obstruction, all these architectures that prevent that freedom from actualizing.”

Lin captured his images while on a road trip along the jagged coast of Bainbridge Island and Port Angeles in Washington, and at home, on the shoreline of New England. This sense of place was palpable in certain frames (like the one which captured a V-shaped coastal cavity) and absent in others (like the close-up of a door that opens onto the sand), allowing the viewer to draw their own associations. Though not the main focus of his show, some of Lin’s images are underpinned by an awareness of American westward expansion.

“I was thinking a lot about Manifest Destiny and this kind of wild, untamed coast,” Lin said. “Back here on the East Coast, where I’m from, New Hampshire, it feels a lot more collective, contained, and domestic, so having to wrangle that was interesting. The process was very much a documentary process, I would just go out to the beaches and shoot and then it was through editing and sequencing the photos that the ideas came through or were formulated.”

As the viewer looks down from Lin’s installation to ponder their own materiality, they could be led towards “Paintings,” a series of floor-situated pieces by Eric Roe ’21 that features a more abstract expression of material and portraiture. Beginning with a trail of quickly-produced self-portraits, the installation led to a colorful set of four self-portraits before opening into a room with two thickly painted canvases. Ordering his pieces from quick and light to dark and heavy with paint, Roe prioritized the physicality of his work, hoping to remove his process from conceptual formulations.

“I wanted the presentation to be flat, neutral, matter-of-fact,” Roe wrote in an email to The Argus. “It felt unfair to the work to reduce it to being ‘about’ something or other, because to be ‘about’ seems like a peripheral existence in the world of ideas…When I work on a painting, I have no idea where it’s going. I could think I’m done, be happy with the painting, then find myself painting over everything, making it into something else. All the objects are the results of that energetic process, where my hands and eyes are trying to bring something honest and true into the world and hopefully my brain is elsewhere.”

As I considered Roe’s work more closely, careful to watch my step, I began to see the motion within his 20 depictions of the face. The 16 quick self portraits, which were made using a paper towel, capture the movement of the artist’s eyes, darkening around points of fixation such as the mouth or the nose. His four painted self-portraits employed harsh color contrasts and brushstrokes that imbued each of their subjects with a distinct personal energy. Rather than idealizing the artist, Roe’s pieces appear as the result of observation and reproduction, intimately connected to the process of their creation.

“[I] started putting myself into the work directly, in the form of these self portraits,” Roe continued. “Four were in acrylic and they were like gargoyles. The other 16 were more like ghosts. The pandemic helped get me to the point where I could actually produce self portraits to my standard of honesty, I think, because after so much time alone, my relationship to my own image had shifted. I stopped caring how I looked, so much that when I looked in the mirror I wasn’t searching for an image that was really in my head, but merely saw the features of my face like parts of a landscape.”

Dotting the landscape of Wesleyan’s Center For the Arts (CFA), an architecture thesis by Amy Schaap ’21 added colorful structural additions to various features of the University’s built environment. From a curtain of blue strands encircling the fountain outside of Davison Art Center to an orange hood covering one of the staircases to the CFA Theater, Schaap’s project split up the monotony of the CFA’s gray, concrete architecture. Her creations were represented in the gallery itself by five small drawings, an illustrated hint to the powerful structures waiting outside.

Back inside the gallery, an installation entitled “Rending” by Sam Javellana Hill ’21 commanded the entire height of one of Zilkha’s walls with drawn-upon reams of brown paper stitched with fishing line in various states of unravelling and disintegration. Expressed through a meticulously developed assemblage of materials, Hill’s creative projections played with the viewer’s relationship to the space.

“I started using the scroll form because I wanted something that felt continuous, [something] that connected to process and wasn’t just an object like a piece of paper on a wall,” Hill wrote in an email to The Argus. “I think the large piece was more successful than the small pieces in that it felt more like a substance than a surface. In the large piece, I let gravity dictate how it was constructed. It crashed into the floor and spilled out and I let it become more sculptural by repairing it in different ways.”

On the surface of the paper itself, Hill’s abstract forms reminded me of body parts, following naturalistic patterns of curvature and interconnection. This effect was aided by the various tones of white and dark charcoal Hill employed throughout the piece, stretching the material to its representational limits. Rather than tell viewers what the torn-up paper reams represented, though, Hill’s markings intentionally left much to the imagination.

“I’ve deeply enjoyed hearing what people see within my work,” Hill continued. “I’m uninterested in telling a clear narrative. I’m uninterested in my story being legible to my viewers. What I am deeply invested in is creating an emotional experience. My biggest aspiration for this piece was that viewers would spend time with it and think about it even after leaving the gallery. Most importantly, I hoped that it would stir feelings within them. I’ve had people tell me that in this piece they see mycelium, moss growths, a tree, bodies, or even architectural forms.”

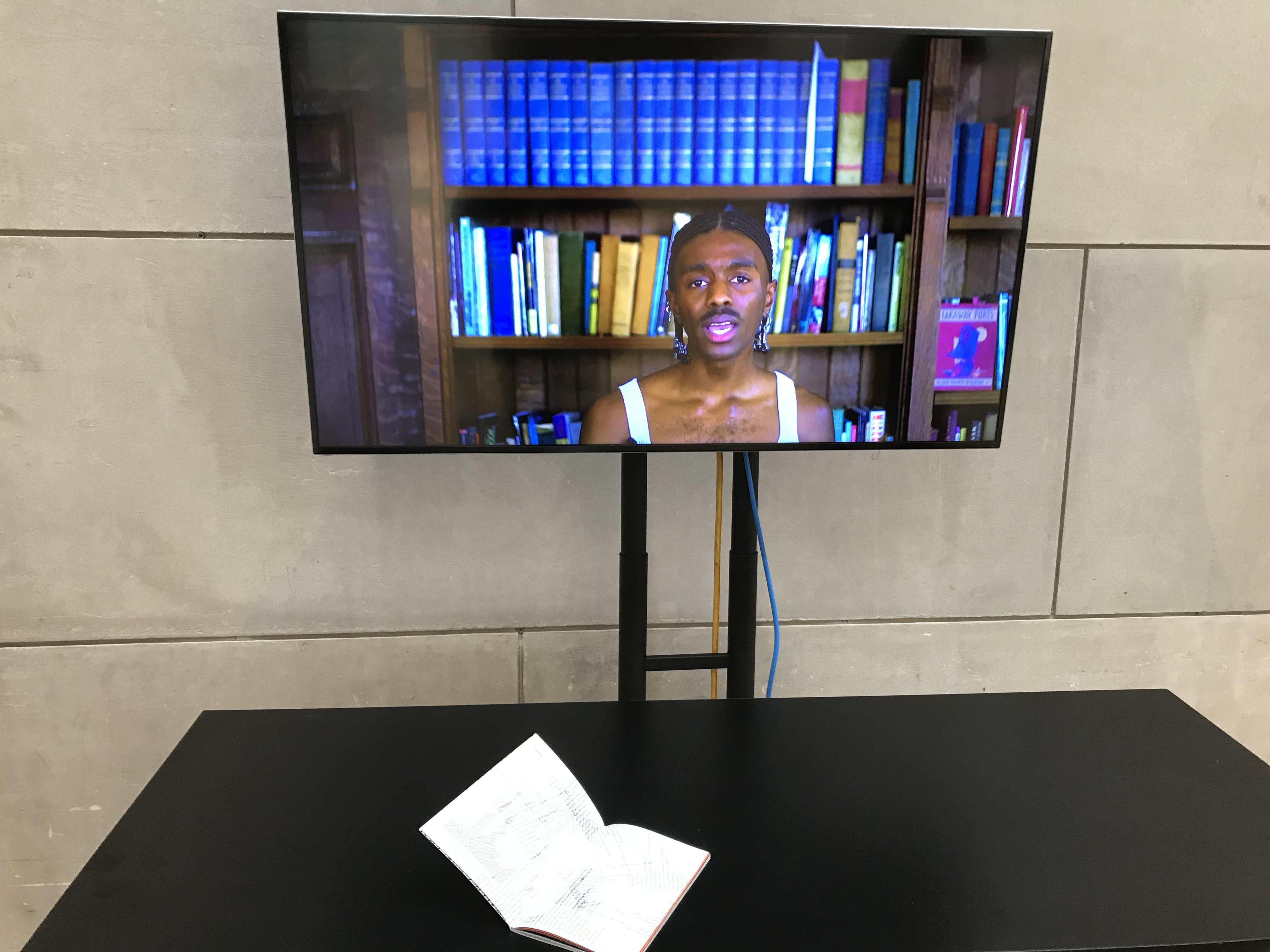

Calling out from the gallery’s back bay, “Queer Boi But I’m Perfect” by Kyron Rizzo ’21 offered a direct yet multifaceted expression of queer, Black identity. Centered around a highly-saturated video of Rizzo reciting various poems from their book, which is placed on a table in front of the screen, the piece surrounded its audience with lyric, rhythm, and projection. To the right, a headphone-equipped projector projected the expanding and contracting image of a poem onto a single white block while playing a Nicki Minaj beat sampled by Rizzo. On the left, another projector displayed its image onto a series of rectilinear white pedestals, offering its own pair of headphones with which one can hear the artist’s poetic remix of Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s “WAP.” As Rizzo explains, this all-encompassing project was never meant to be defined by the confines of a traditional gallery space.

“At first I was like, I don’t have to worry about setting up in the actual space ‘cause COVID just won’t allow me to be on campus. Another part of me was also like, I am not creating as a Black queer artist who likes to deconstruct traditional institutionalized structures, I know in my heart that when I do create art I am not creating for an institution or to be set up in a very institutionalized space,” Rizzo said. “We think of what is mounted or put on a pedestal in contrast to what happens when that piece or that work is missing or not there. So I was thinking about, when I was setting up my space, that my work is not part of the gallery in that sense—it’s moving, it’s in flux, so that’s why even the work itself is not on [something]. It’s projected onto something.”

Despite its purposeful dislocation within Zilkha, Rizzo’s expressions are connected with a range of literary, poetic, and musical influences. The beams of projection onto white pedestals, which the viewer could easily intercept, recalls the ending of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” in which the protagonist uses lights to illuminate himself while truly requiring illumination from within. Rizzo’s command of spoken-word arises from an admiration of Amiri Baraka’s legacy across music and poetry. The use of “charlie” by Rizzo to refer to whiteness in a text meant for queer people of color calls back to James Baldwin’s play “Blues for Mister Charlie.” Rizzo’s hip-hop background looms large throughout their work, drawing from figures such as Biggie, but also incorporating rhythmic and musical structure into almost every element. Nevertheless, the fluctuating, un-situated nature of Rizzo’s art is a crucial part of their viewers’ experience.

“A big line in my work, that my advisor pointed out, was ‘path of pleasurable refuge’ and not ‘path to pleasurable refuge,’” Rizzo explained. “I make an important distinction between not being a path to something because so many times queer people, Black people, and queer Black people especially, have been used as a means to an end, a means to get to something, for us to use our talents our minds, our creative intellect to do something for someone else or others, and so I’m really harping on the fact that I am a path of pleasurable refuge.”

Towards the gallery’s door, in its own room, was “The Carrier Bag,” a video installation created by Sarina Hahn ’21 centered around the rear-projection of a VHS onto a piece of stretched canvas. This apparatus made for an unconventional viewing experience in which you could see the setup at work without the chance of obstructing the projector’s view. Once synonymous with home video-making, the VHS tapes that powered Hahn’s narrative projected a film that was laden with associations of familial memory.

“The ostensible subject matter of the piece (my relationship with my father and his work as a Jewish chaplain in a hospital where I grew up) opened up through this context of formal experimentation,” Hahn explained over email. “Questions about what it means to be in relation, the mediation of the (VHS) camera as a certain way of looking or knowing, and narrative structure all emerged together in this way, resulting in the installation in Zilkha last week.”

These themes of memory and relationship resulted not only from Hahn’s formal experimentation with the medium of VHS, but also the pandemic-induced conditions in which they created the piece. Sent back home with the rest of Wesleyan’s campus, Hahn found their subject in a crucial relationship given new centrality by the pandemic.

“Studying remotely in my hometown this past year allowed me to spend time with my father, which I otherwise wouldn’t have,” Hahn continued. “Some of the questions about lasting and narrative carrying in the piece became connected with my father’s work spending his days with sick and dying people, which of course intensified in new ways during the pandemic.”

Planned, re-planned, and executed in a year of constant transition and reflection, the art of last week’s exhibition thoroughly existed outside of the limits of Zilkha and the University as a whole. As not every artist was able to see the finished exhibition, conversations between pieces and viewers ultimately occurred both in person and in a novel, digital space. Despite the event’s impression of finality, the art itself evaded structural and temporal boundaries, begging questions of setting through transitory materials. This years’ theses offer a unique opportunity for us to reassess our position towards a medium that thrives from its own deconstruction and recreation.

Timed-entry tickets for week two and three of visual arts theses are available at the CFA box office.

Aiden Malanaphy can be reached at amalanaphy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply