One of the most memorable scenes in “Miss Americana,” the Netflix documentary about Taylor Swift released last month, occurs in the final third of the movie, as Swift watches footage she has just filmed for a music video.

“Yeah, I have a really slappable face,” Swift says ruefully, going on to compare herself to a rhino as crewmembers gently demur.

A certain wry self-awareness about how she comes across has become a part of Swift’s brand in recent years, occasionally to great effect (as in the near-perfect song “Blank Space”) and more often to mixed results (as in the entire album “Reputation”). But her comments here are still surprising in their bitterness, less of a performance than a genuine and unscripted moment of insecurity. The footage segues into a glittering montage of Swift’s live performances through the years, set to a not-quite-rousing speech about the impossibility of keeping up with industry expectations for women. The whole scene feels like an apt summary of the documentary as a whole: a carefully calculated narrative that nonetheless reveals flashes of surprising candor.

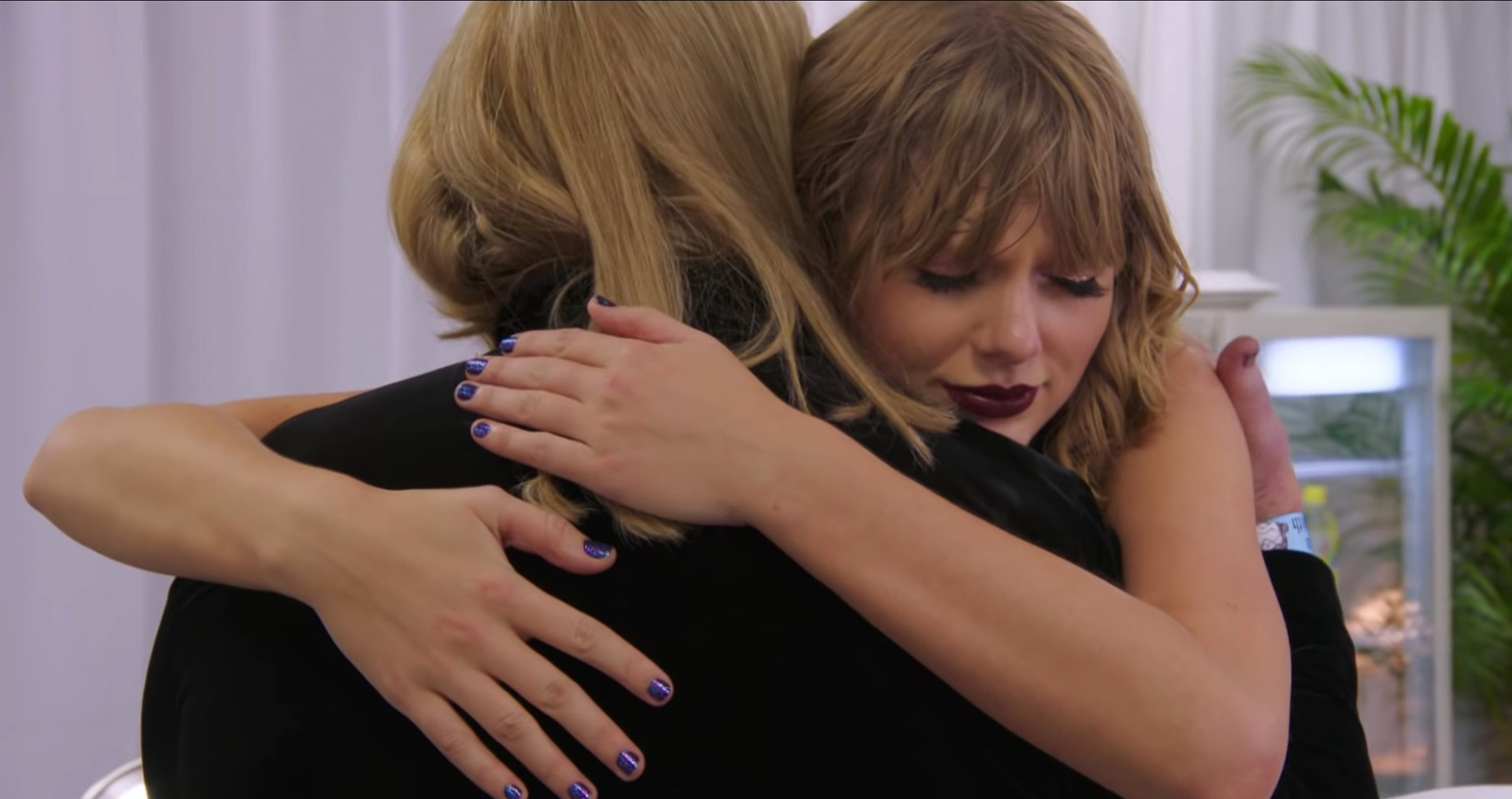

“Miss Americana” charts Swift’s public rise from ingénue to superstar, but its real focus is behind the scenes on the singer’s emotional journey. The film stitches together glossy, professionally filmed performances and interviews with cell phone videos and grainy footage of Swift’s youth, which help give it a rawer, more unscripted appearance. This appearance is, of course, an illusion; every choice in “Miss Americana” is intentional. I was—and remain—skeptical of any form of celebrity confessional that purports to reveal the unvarnished truth about its subject, but I found myself surprised and even moved by parts of the movie. One such scene occurs when Swift speaks openly for the first time about her experience with eating disorders. Watching her visible hesitation while describing her habit of scrutinizing photos of herself for signs of weight gain, I felt a twinge of recognition, followed by an unexpected rush of tenderness.

I believe Swift when she talks about her struggle with body image, and I commend her honesty. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who felt similarly sympathetic, which is why I’m also sure it’s not accident that this scene immediately precedes one about Swift’s multi-year feud with rapper Kanye West. This feud culminated in 2016, when Swift expressed outrage over a derogatory line about her in West’s song “Famous.” West’s wife, Kim Kardashian, then responded by releasing a recording of a phone call between the two musicians in which Swift appeared to approve her inclusion in the song. The “Famous” scandal marked a turning point in Swift’s public perception (who avoided the public eye for almost a year afterwards), and remains the moment many of her critics cite as evidence of her manipulative nature. Swift’s apparent duplicity quickly became a kind of cultural shorthand for the ways in which white women often capitalize on their perceived innocence and purity. In “Miss Americana,” Swift manages to sidestep the whiny insistence on victimhood that drew so much ire four years ago, but still comes off as somewhat self-centered, emphasizing her own feelings of shame and embarrassment and avoiding any real explanation of her actions.

The most honest part of Swift’s recounting is her description of her all-consuming desire to be liked. This need for validation is one of the themes running through “Miss Americana,” and Swift is unflinching about the extent to which it has motivated most of her past choices. The tension between avoiding criticism and being true to herself leads to the climax of the film, about Swift’s political awakening. After years of avoiding any public discussion of her political beliefs, Swift broke her silence during the 2018 midterms by publicly endorsing Democrats running in Tennessee. In “Miss Americana,” Swift describes these events as if her conscience would no longer allow her to stay silent, and there may well be truth to that. It’s likely also true that by 2018, in the age of “Queer Eye” and “Drag Race,” it was no longer particularly risky to come out as a feminist or an ally to LGBT+ people (particularly not when one engages in the kind of frilly, primarily aesthetic allyship that Swift does).

I believe that Swift wants to be a good person, but I also know that she wants to be perceived as a good person, because she says so herself. What is less knowable is the degree to which each of these impulses drive decisions like her choice to avoid and then embrace politics, or to leave the spotlight and then return to it. For all its emotional interviews and teary confessions, I ended “Miss Americana” no closer to answering these questions than I started it.

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply