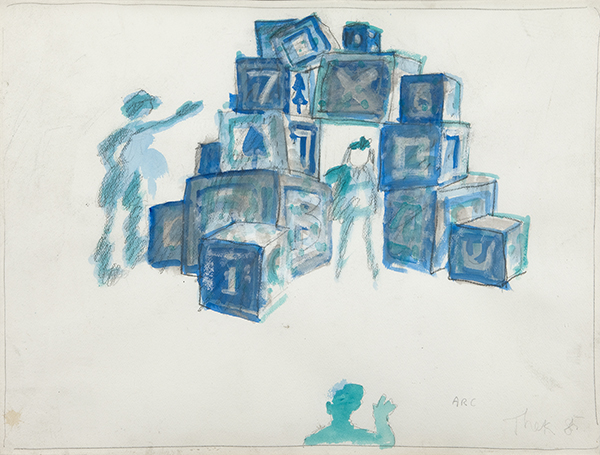

Child’s Arc De Triomphe, 1985

pencil and watercolor on paper

18 x 24 in/45.7 x 61 cm

photo: Bill Orcutt

©Estate of George Paul Thek, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Poet Susan Howe and musician David Grubbs performed “WOODSLIPPERCOUNTERCLATTER,” a collaborative piece blending piano, poetry, and field recording, on Tuesday, Feb. 11 in the Zilkha Gallery. The performance put fragmented stanzas from Howe’s 2017 collection “Debths” in conversation with Grubbs’ minimalist piano phrases and soundscapes emanating from a laptop situated between them. The concert’s setting—among the architectural-inspired sculptures of Diane Simpson’s “Cardboard-Plus” exhibition— underpinned these elements. Truly multidisciplinary in its approach, the resulting experience provoked critical questions of how art is to be absorbed, interpreted, and repurposed.

Surprisingly, the first thing I heard as the duo took their seats was not poetry or piano. Instead, the performance began with what sounded like echoey footsteps and hushed voices, playing through speakers placed throughout the gallery. Disembodied and unexplained, the seemingly pre-recorded audio pushed audience members to piece together their own interpretations of what was being expressed, a process that would define the performance to come. Seeing that the performance took place in a gallery, I imagined the sounds as a recording of two people walking through an exhibition and whispering to one another about what they saw. The sounds, which would evolve to include a kind of chirping, nevertheless remained ambiguous in their meaning, positioning the audience into a space of wonder, similar to the wonder one might feel when viewing an abstract work of art.

As the gentle pulses of Grubbs’ piano chimed in, making sense of what I heard became no easier. Proceeding slowly from single notes to chords, the repetitive sounds complemented the field recordings, which still formed the backbone of the piece. With little melody or variation, the piano, which would reappear throughout Howe’s reading, kept the performance in a state of open-endedness, refusing to provide the audience with a tangible explanation to rest upon. The decision to include the piano was one of the many ways this performance evolved from Howe and Grubbs’ previous collaborations. In works such as their 2011“Frolic Architecture,” for example, similar use of laptop sounds as a background for Howe’s recitation were not complemented by an instrument. Here, the piano served the function of visual familiarity, yet was paired with indecipherable playing, both comfortable and foreboding in its effect.

These elements provided the perfect entrance for the disjointed, cut-up verses of Howe’s poetry. Equally as anti-expressive as the field recordings and piano playing, Howe’s poems were comprised of seemingly disconnected snippets; they lacked the level of narrative coherence that might be able to resolve the barrage of questions the piece’s musical components posed. Phrases such as “a work of art is a world of signs” were paired with incoherent, splintered words that sounded like Latin, and lists of materials that could be found on a museum placard. Even the cultural references that dotted the recitation, such as Titian or the fairytale “Tom Tit Tot,” provided little comfort and equally little context to the audience. As Howe explains in the foreword to“Debths,” this incoherency was entirely intentional, and was inspired by “folktales, magic, lost languages, riddles, coincidence, and missed connections.” Stripped of individual meaning, Howe breathed feeling into her words through shifts in tone, from soft and informative to loud and urgent. Familiar meaning remained out of reach throughout the reading, though, which made listening to the recitation an active work of personal interpretation.

The show’s location in the middle of Diane Simpson’s exhibition “Cardboard-Plus” contributed further to the show’s theme of tangled meaning. Like Grubbs’ sounds and Howe’s phrases, Simpson’s cardboard cut-out sculptures leave much to interpretation. As Simpson explained during the gallery opening, her structures and abstract forms were inspired by architecture, geometry, and fashion, often incorporating each of these elements in a single piece. Simpson’s 1978 work “Leaning Lookout,” for example, could resemble both a building or some kind of device depending on who is looking. Her 1980 sculpture “Fold Up,” which was positioned directly to the right of the audience, looks like a hospital stretcher at first glance, but ultimately lacks a clear use as a utilitarian object. The performance did make reference to art directly, but it also required a process of personal interpretation, one which closely resembles that which Simpson requires of her viewers. As I looked around throughout the show, Simpson’s sculptures became lumped into the experience of parsing the meanings of ambiguous artistic gestures.

By the end of the performance, the 4 elements at play had melded into an enjoyable, thought-provoking expression of artistry. Music, poetry, field recording, and visual art, each given their own space of entry, became perfectly synthesized into a single experience. Endlessly elusive in meaning, “WOODSLIPPERCOUNTERCLATTER” represents a paragon of multidisciplinary practice, defying boundaries of genre and time.

Aiden Malanaphy can be reached at amalanaphy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply