This review contains mild spoilers for “Russian Doll.”

In the interest of full disclosure, I should probably admit that the best way to experience brand new Netflix Original “Russian Doll” is with no background knowledge whatsoever. So if you’re lucky enough to have avoided reading any of the thousands of endorsements that have flooded Twitter in the past week or seeing the trailer automatically play when you open Netflix (seriously though, why are they doing that?), you might consider skipping the rest of this review and going in blind. If, like me, you’re too paranoid to watch anything without reading someone else’s opinion about it first, consider yourself warned.

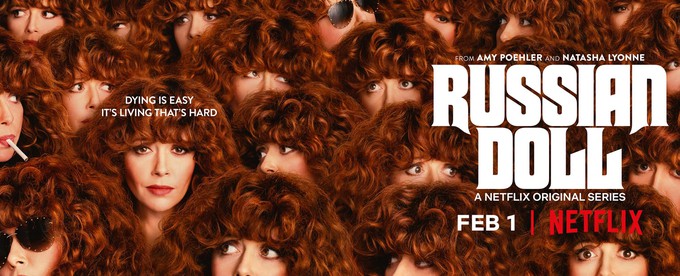

“Russian Doll,” (co-produced by Natasha Lyonne, Amy Poehler, and Leslye Headland), opens on protagonist Nadia Vulvakov (Lyonne) staring at herself in the mirror of a cavernous bathroom, apparently steeling herself for the chaos outside. Nadia is at her own 36th birthday party, in the unbelievably luxurious loft of her friend Maxine (the loft in question is actually a converted yeshiva in the East Village, which is both a major plot point in a later episode and the cherry on top of Greta Lee’s spot-on portrayal of Maxine as a parody of an artsy trust fund kid), but she doesn’t seem particularly excited to be there. Nadia floats disinterestedly through the party, chain-smoking, delivering nonchalantly philosophical monologues about confronting her own mortality, and eventually going home with a sleazy professor (Jeremy Bobb).

Up until this point, “Russian Doll” is nothing more than another addition to an endless list of shows about debauched, disaffected millennials (albeit a particularly well-written one). But then, just as you think you know what you’re getting into, Nadia leaves her apartment late at night to buy cigarettes and crosses the street only to be hit by an oncoming car and die instantly. Bystanders scream in horror and the camera zooms in on Nadia’s lifeless eyes, only to suddenly cut to her, alive and unscathed, back in Maxine’s bathroom at same birthday party she’s already been to. She goes through her entire birthday again, wondering if she’s just suffering from a bad case of déjà vu, only to leave Maxine’s apartment and die again—this time by falling into the East River—and again, and again, and again.

Of course, it’s impossible to create a show about someone being caught in an endless time loop without drawing comparisons to the beloved film “Groundhog Day.” There are certainly similarities beyond the stories’ basic premises—from the upbeat song that signals a timeline reset (“Gotta Get Up” for Nadia, “I Got You Babe” for Phil Connors) to the prickly, misanthropic protagonists—but “Russian Doll” is more than a 2018 version of “Groundhog Day.” The most obvious difference is that Nadia actually has to die—instead of just going to bed—for her timeline to reset, and the show takes full advantage of this. Nadia’s deaths are often a source of humor (Lyonne is a gifted physical comedian, and her frequent fatal run-ins with a flight of stairs outside Maxine’s apartment are a particularly entertaining running joke), but they are often uncomfortably graphic as well. Blood drips, bones crack, and Nadia starts to look more and more exhausted each time she reappears in the bathroom. This combination of black humor and genuine pain is representative of the show as a whole, which deftly walks the line between comedy and melodrama.

Another notable difference between “Russian Doll” and “Groundhog Day” is that Nadia isn’t alone. A few episodes in, moments from dying yet again (this time in a free-falling elevator), Nadia spots a man who seems suspiciously calm about his impending fate. As it turns out, Alan Zaveri (Charlie Barnett), the man in question, isn’t panicking because he is stuck in the same loop of endless deaths as Nadia. It’s at this point that the show really picks up, going from a spiky, existential comedy to something more mysterious. Alan and Nadia race to figure out what connects them and how to break their endless loop, but the more they are forced to relive the same night, the stranger it gets. Fresh flowers wilt, fruit rots, and pet fish (and eventually actual humans) start to disappear without warning. As the world around her seems to come unstuck, Nadia starts to worry that she may be running out of the one thing that seemed to be infinite: time.

Lest that last paragraph make “Russian Doll” sound like some kind of science fiction thriller, I promise it’s much more: a snarky comedy about New Yorkers, a meditation on the nature of trauma, an argument about the importance of human connection, and yes, kind of a thriller. The show welcomes a multitude of interpretations; Lyonne has spoken in interviews about the ways in which she was inspired by her own struggles with addiction and self-acceptance, while a viral Twitter thread (seemingly confirmed by both Lyonne and Headland) convincingly outlined the ways in which the show reflects New York’s collective guilt over the Tompkins Square Park Riots. Perhaps above all, “Russian Doll” is a showcase for Lyonne’s formidable talents. Without her powerhouse performance as Nadia, all the show’s complicated philosophical ambitions would undoubtably fall short. Equal parts prickly and pitiful, Nadia is a deeply affecting reminder of the constant struggle to find meaning in an unsympathetic world and the difficulty of personal growth. Sometimes you have to die a few times to learn how to live.

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply