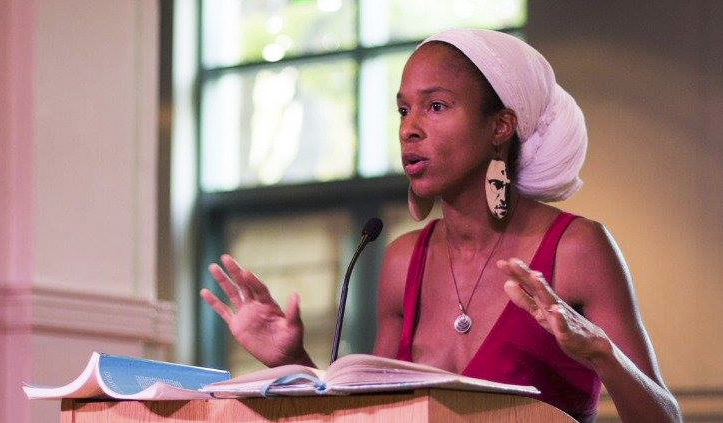

Dr. A. Breeze Harper Discusses Privilege and Exclusion in Vegan and Buddhist Spaces

Last Thursday, creator of Sistah Vegan Project Dr. A. Breeze Harper gave a lecture at Russell House about engaged Buddhism, ethical consumption, and anti-racism.

The lecture, titled “Mindful and Deluded,” was organized by Veg Out and Women of Color House. Dr. Harper’s talk tied together topics in activism, compassion, and responsibility within the modern context of oppression that persists in America.

Dr. Harper’s expertise is wide ranging. Trained as an African American critical race, feminist, critical food, and whiteness studies scholar, she connects these fields with her personal experiences in her work.

Beginning the talk with a song, Dr. Harper brought into focus the persistence of oppression and racism in 21st century America. The lyrics of the song talked about resistance to the auction block, and Dr. Harper explained that veganism can be used as a platform for discussing the consequences of the auction block in a largely white nation.

The auction block is an instance of an abuse of geography to arrange people. Geography, not only physical but also psychic, has historically been the domain of white men who created mainstream spaces. Dr. Harper discussed that the ways in which black women relate to space and place is different from the mainstream ways established by white men.

Veganism, to Dr. Harper is an example of a kind of space created within an oppressive system that has the potential to bring people together for the purpose of perpetuating good, nonviolent, progressive values.

Despite its existence, this space is still largely exclusionary. Dr. Harper claims that she has rarely ever met any Black vegans. She began to question what vegan spaces look like within mainstream America and posed an open question to the community on the topic of whether race and gender impact people’s experience as vegans.

Her question was met with intense anger and backlash. Most of this anger was rooted in racially coded language amongst people who considered themselves “progressive vegans.” Despite their so-called progressive values, they used racially coded language and dismissed the Black struggle under the pretext that it undermined veganism’s mission to alleviate the suffering of nonhuman animals. This interested Dr. Harper because it showed a departure from the mainstream norm behavioral expectations by liberal and progressive communities. Dr. Harper studied this topic in her years at Harvard University and received the Dean’s Award for her work.

“Something is deeply wrong with the way that people perceive what is and is not covert racism,” she said.

Dr. Harper also recognized this departure from expected progressive and liberal norms in the Buddhist community. Dr. Harper lives in the Bay Area, where Buddhism is extremely popular. The way that people engage and interact with Buddhism is largely rooted in and limited by class and privilege. Like progressive vegan spaces, Buddhist spaces are occupied by people who are predominantly wealthy and white. Despite the fact that the precepts of Buddhism stress compassion and alleviation of suffering for all human beings, people within the community often choose to ignore that its exclusivity and demographics can cause intense pain and suffering for people of color. When Dr. Harper discusses race in these spaces, the community claims that she focuses too much on ego, and that the focus should instead be the elimination of labels.

This denial shows how coded racism continues to operate, even in supposedly liberal spaces fixated on compassion and equality. These communities fail to recognize their positionality, subjectivity, and privilege. The 19th century appropriation of Buddhism through translation has specifically made it accessible to white people, fitting it into an already existing white supremacist framework. When practitioners of Buddhism claim that they are above race, they ignore how their conception of Buddhism is marred by a history of privilege. The ways that one engages in Buddhism are subjective and often not part of mindfulness discourse. Dr. Harper claims that although we should acknowledge that suffering can never be completely alleviated, recognizing one’s positionality is crucial to working towards this goal.

“It is delusional and unmindful to pretend that race and class don’t matter,” she said.

Bringing up issues surrounding race in ostensibly progressive communities often causes anger because it conflicts with values that people claim to embody. A false conception of self-identity is challenged through the validation of other voices. Dr. Harper proposes that only by asking more questions and challenging this incomplete progressive notion of the self can people challenge the investment that many of these people have in their whiteness.

In a post-lecture Q&A, Dr. Harper addressed questions regarding identity, the Trump administration, and activism. Replying to a question about whether the Trump administration has made her work more difficult, she claimed that while it often times did, it also helped her better understand and study the dynamics of liberal whiteness. She recognizes that Trump is used as an example against which one can define oneself as the more “woke white person.” His administration provides a lens for comparing spectrums of racism.

Another student asked how to invite more people of color to the largely exclusionary movement of food sustainability and environmentalism, especially on the University’s campus. Dr. Harper responded that they should be directed to Sistah Vegan Project’s work, which deals a lot with inviting and integrating people of color into these movements and communities. To make these spaces more accessible, groups should change implicitly coded language and gain racial literacy.

Emma Grover ’21 posed the question of how Buddhism can be reclaimed by other groups when it is largely appropriated by white men and how that conversation can be started. Dr. Harper said that this could be done by redefining and creating new definitions for Buddhism. People should move away from the concept of authenticity and instead find a representation of Buddhism, or any given practice, for themselves. If an appropriate representation does not exist, individuals should create one.

Ingrid Eck ’19, who helped organize the event, believes that this talk is extremely important for the University community to hear and experience.

“Mainstream environmentalism has so much room for improvement—we need to actively practice anti-racism, we need to embrace intersectionality,” she said. “Environmental justice should be at the forefront of the movement.”

Students can embody the ideals of liberalism, equality, awareness, and anti-racism by recognizing them as a common thread in all communities.

“I hope that students or community members who are involved in environmental or spiritual communities share what they have learned with these communities,” Eck said. “I’m proud of the inclusive environment Veg Out creates but this talk was a much-needed reminder that anti-racism should be the top priority for our organization.”

Steph Dukich can be reached at sdukich@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply