FGSS Hosts Symposium Focused on Black Health and Hidden Stories

Director of the City College of New York’s Journalism Program Linda Villarosa and Assistant Professor of Black Studies and Sexuality and Women’s and Gender Studies at Amherst College Khary Polk spoke at the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (FGSS) annual Fall Symposium on a panel about HIV/AIDS and queer historiographies.

The panel, organized by Associate Professor of Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and English Lisa Cohen, discussed Villarosa’s process of writing her New York Times article about how HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects black gay and bisexual men in America. Polk discussed his intersectional focus on black queer sexuality and how homonationalists have historically avoided discussing the Watkins v. United States Army case and its surrounding history.

Villarosa first presented the process of her involvement in reporting on HIV/AIDS, beginning with her 1985 reporting on gay-related immune deficiency (GRID), as it was known at the time, for Essence Magazine. She interviewed a mother who had the disease for an article and noticed the mother’s baby was also sick. Before the publication of the article—which was the first story by an ethnic publication about GRID—both the mother and baby died. However, Villarosa was optimistic that the government would fund efforts to cure the disease.

In 2016, while teaching at City College, she stumbled upon two reports: One said that if all things remain the same, half of black gay and bisexual men will have HIV/AIDS in their lifetime, and the other stated that most new cases were in the South, with Jackson, Miss., having the highest rate of new diagnoses. After getting advice from old journalism contacts, she flew to Tennessee to attend the Saving Ourselves Symposium to learn more about the issue.

After the symposium, where gay black men held panels and brought ministers to speak, Villarosa pitched her article to The New York Times Magazine. In response, they said her take was too optimistic and that she had to find out who was to blame for this epidemic. She received the assignment and then travelled to Jackson to do more interviews.

While Villarosa was trained as a serious journalist and her education emphasized objectivity, she has changed her approach due to the state of the country.

“I’ve turned [my formal training] upside down,” Villarosa said. “Everything I thought is changed. I have started calling myself a resistance journalist, and I’m lucky enough to have The New York Times Magazine editors believe in my work.”

In Jackson, Villarosa conducted the interviews that she later used to write an article in The New York Times Magazine. Instead of the origin of the issue being the affordability of healthcare, she realized people were reluctant to enter the healthcare system due to Jackson’s small community.

Villarosa concluded her speech by talking about a call she received after publishing her article. The head of one of the organizations in Jackson that offered support to people diagnosed with AIDS, My Brother’s Keeper, called Villarosa crying. She told Villarosa that they were getting a huge surge of donations and that she hadn’t thought anyone cared.

“I write about AIDS, inequality, social justice, and public health, but what I really write about is love,” Villarosa said.

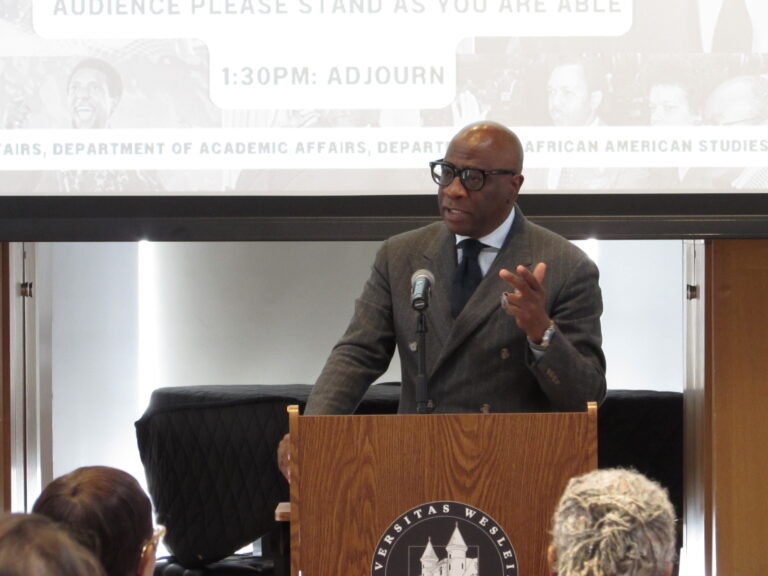

Polk then took to the podium to talk about his research on the case of Perry Watkins, an openly gay army veteran who won a case against the army when it attempted to discharge him right before he was eligible for pension, and how both strands of homonationalist thought avoided discussing Watkins’ case in part due to Watkins’ identity as a black gay man.

He first described what homonationalism is.

“Homonationalism is understood here an apt analysis of the way repressive state apparatuses appropriate discourses of sexual and gender rights to manufacture consent for military intervention amid national projects of inclusion and exclusion,” Polk said.

He described the two branches of homonationalist thought: homonationalist inclusion, or activism of gay conservative groups campaigning for gay and lesbian soldiers to serve openly, and homonationalist refusion, which included groups like Lesbian and Gay Men Against Intervention who combined anti-militarist and queer left thought into their activism.

After Watkins was conscripted to the army because a psychological evaluation deemed that he lacked the proof of his sexuality that would keep him from being able to serve in the military, he was assaulted by five men in his barracks. He reported the incident to a supervisor, which led to an investigation against Watkins himself that again said there was insufficient proof that he was gay. Watkins announced that he would take any future assault but that his assaulters would have to sleep eventually; then he would strike back. He had no more trouble with other soldiers after that.

Watkins began to view military service as a contest and reenlisted three times. He also began to do drag shows, performing as Simone Monet with the consent of his superior officers. However, the military attempted to discharge him in 1984, right before he was eligible for his pension. A 1989 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling ordered that he be reinstated, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case after the Bush administration appealed it. Watkins received his pension and full military honors.

Despite being the only person to win this type of case against the military, Polk said, those fighting for gay rights in the military refused to incorporate Watkins’ narrative into their fight, saying it was too narrow and that he was always open about his sexuality, so it did nothing to attack the policies head on.

Watkins viewed this refusal as structurally racist, and Polk quoted a speech in which he articulates this thought.

“‘If the gay and lesbian community were to have chosen a person to win, it damn sure wouldn’t have been a black person,’” Polk read. “‘It wouldn’t have been a little black nelly queen from Joplin, Missouri.’”

Polk then tied Watkins’ case to modern military exclusion of transgender soldiers and how the historical treatment of Watkins’ case is being repeated today.

“Beyond the lack of critical engagement with Perry’s story itself, on a structural level, [the legacies of homonationalist inclusion and homonationalist refusal] highlight a blind spot in our understandings of the way race, gender, and sexuality have been and continue to be entangled in American militarism in our contemporary moment,” Polk said.

Jocelyn Maeyama can be reached at jmaeyama@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply