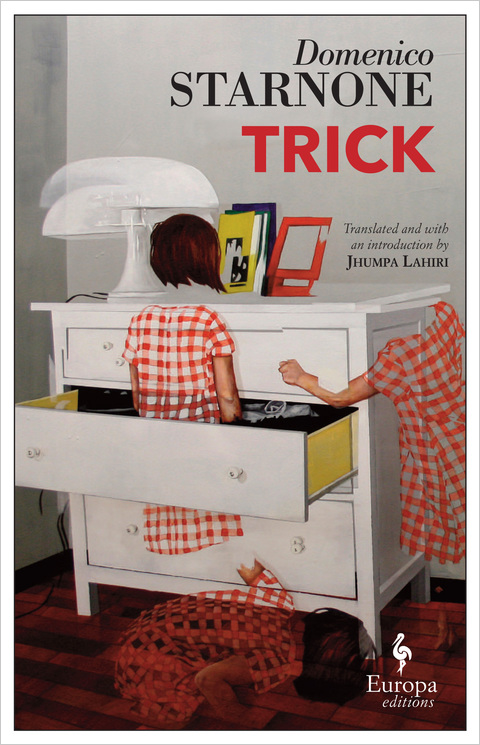

Crowds gathered in Wesleyan R.J. Julia Bookstore on Monday night to hear Domenico Starnone read from and discuss his latest novel, “Trick.”

Starnone, an Italian writer from Naples who has worked as a novelist, screenwriter, and journalist, was joined by Jhumpa Lahiri. Lahiri, known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning short story collection, “Interpreter of Maladies,” translated Starnone’s work from Italian into English. Michael Reynolds, editor in chief of Europa Editions, which published Starmone’s novel, moderated the event, and University Dean of the Arts and Humanities Ellen Nerenberg translated Starnone’s comments into English.

“It’s like asking Picasso to paint with his left hand and still ending up with a brilliant Picasso,” said R.J. Julia owner Roxanne J. Coady. “That is what Jhumpa has done with her book and her splendid translation of Domenico’s book.”

“Trick,” Starnone’s thirteenth work of fiction, follows aging illustrator Daniele Mallarico as he revisits his native Naples to look after his four-year-old grandson, Mario. Mallarico is struggling with both his professional and his personal life; his artistic career is in decline, and the return to his childhood home brings back unwanted memories of his troubled adolescence.

In one passage, which Starnone read aloud in the original Italian and was followed by Lahiri with her English translation, Mallarico grapples with his anger at having a recent set of illustrations harshly criticized by his publisher. He keeps returning to one word: “’a raggia,” or rage.

“That word was frowned upon in school,” Lahiri read aloud. “Teachers and professors would correct us. ‘Not rage,’ they would scold. ‘We say ire. Rabid dogs rage’…. My father and grandparents and great-grandparents, maybe all my ancestors put together, didn’t know the word ire…. They only knew ‘’a raggia,’ rage…. Teachers and professors gave us a vocabulary that was useless on these streets.”

This complex relationship between language, emotion, and meaning was a theme both Lahiri and Starnone kept coming back to over the course of the event.

“It’s a passage in which the subject is language, so for a translator, it becomes a sort of meta-translation project in that I have to explain language itself,” Lahiri said. “I preserved [‘’a raggia’] in dialect, which is untranslatable—there would be no equivalent, really.”

The same concept—that certain ideas exist only within a dialect, which presents a challenge for translators—touches on the raw emotionality that “Trick” indicates is instinctively expressed in one’s native language.

“It was satisfying in that the protagonist was sharing my own predicament as a translator because he too is caught between the language that he ultimately can lean on in a moment of emotional crisis—in his case, the dialect, which is really speaking for his emotional state—and then this overlay of Italian, which isn’t corresponding to his experiences, to his family’s experiences, to the place that forms him,” Lahiri added. “There’s a disconnect between the character and the language that he’s come to own, to possess, to use.”

As Daniele progresses further into a state of crisis, he regresses into his native dialect. Although Starnone was quick to assert that he was very different from his character, he noted that he certainly brought parts of himself into the protagonist.

“Until the age of 10 or 12, I lived my life exclusively in dialect,” Starnone said. “Let’s just say that the majority of my chief emotions had their first formation in dialect. The consequence of this is only that, every time I lose my patience, even without wanting to, the reaction does not come in Italian. The reaction comes out in [my dialect,] Neapolitan.”

Starnone’s experiences, Lahiri emphasized, are the only ones that have a place in “Trick.” Despite her own accomplished writings, she takes care not to incorporate her own personal style into the author’s works.

“I translate the books as a writer, and I’m translating the books for many reasons, but the selfish writerly part of me is translating the book in order to learn how the book is put together, to enrich my language,” Lahiri said. “One of the pleasures of translating, for me, is to see the world constructed in a totally different light, and, of course, in this case, in a different language.”

Starnone and Lahiri each complimented the other for their contributions to the creation of the final work in English.

“[Domenico’s writing] is incredibly clear, though layered and subtle and very intelligent and instructive, but I think, first and foremost, he knows how to tell a story, he knows how to put it together, he knows how to captivate the reader, and does this with a very light touch,” Lahiri said. “There’s a very, I think, admirable tension in his prose that I like—richness combined with clarity that’s very hard to achieve.”

“I’m a fan of Jhumpa’s and I love her writing,” Starnone said. “From my point of view, it’s a privilege to be translated by a translator who’s also a writer. The reason for this is that if you are also a writer, you have something that other translators, who are not writers, don’t have.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @HannahEReale.

Leave a Reply