Last Thursday, faculty and students gathered in the Wasch Center for Retired Faculty to hear Lauren B. Dachs Professor of Science and Society; Professor of Biology; and Professor of Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Laura Grabel discuss her research focusing on current stem cell therapies and the political and religious aspects of stem cell research.

Grabel, who uses embryonic stem cells in her lab, has not only had to overcome many technical difficulties while conducting her research, but many political barriers to embryonic stem research as well.

One of Grabel’s most impressive projects includes discovering whether neuronal stem cells could be used as a potential treatment for epilepsy, a disease that affects over three million Americans. Epilepsy is associated with seizures that can lead to behavioral deficits and memory loss, symptoms which are the result of loss of function of inhibitory neurons in the brain.

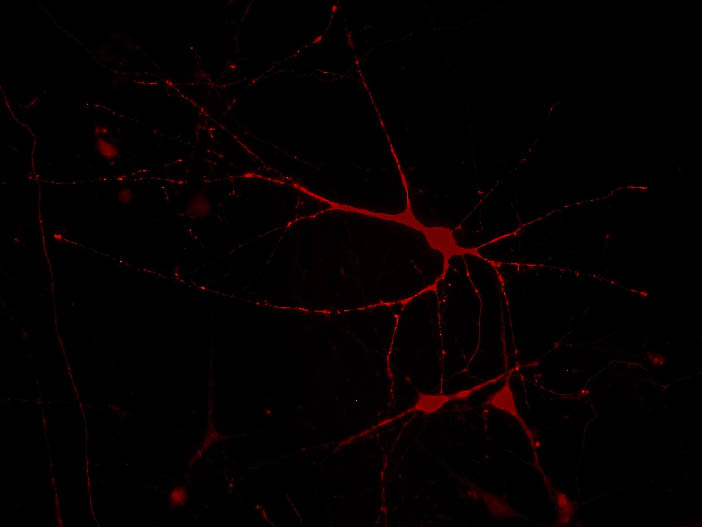

The Grabel Lab, Aaron Lab, and Naegle Lab recently collaborated to see if they could replace inhibitory neurons with inhibitory neuronal stem cells in epileptic mice to decrease seizures and memory deficits. The first challenge was growing inhibitory neurons and testing whether or not the neuronal cells actually functioned like interneurons, neurons that connect to other neurons. The next was figuring out how to successfully implant these neurons into the hippocampus of mice.

“The work that we do is very cool,” said Emily Moon ’21, who works in the Grabel Lab. “The collaboration was about curing epilepsy. The idea that you could use [one’s] own symptoms to improve epilepsy is astounding.”

At the conclusion of the study, the Grabel Lab found that they were able to successfully reduce memory deficits in epileptic mice. However, no change in the length or severity of the seizures was observed. The Grabel Lab is unsure whether or not the implanted neurons are forming functional synapses, which may be why the seizures are not being suppressed.

Grabel thinks that the improved memory may be a result of a molecule being secreted by the implanted neuron, which is diffusing through the neuronal membrane and migrating to the hippocampus to improve memory.

In her talk, Grabel also mentioned three current promising trials that implicate stem cells as a therapy to treat injuries and disease. American companies such as Geron and Asterias Biotherapeutics are using stem cells to treat spinal cord injuries. Grabel also mentioned that stem cells show promise in aiding patients with macular degeneration.

While Grabel is retiring next year, Moon says that the Aaron Lab plans to collaborate with the Naegle Lab to continue to manipulate signaling cascades in epileptic brains to either decrease the number of seizures incurred, or decrease the likelihood that the seizures propagate.

The second half of Grabel’s talk focused on the ethical and political domain surrounding embryonic stem cell research.

“Does the blastocyst have the same rights as you and I have to be or not to be killed?” Grabel asked. “When is personhood ordained?”

One argument for using embryonic stem cells for research is that assisted reproductive technology produces an excess of embryos that are often thrown away if they are not used for research.

According to Grabel, these embryos are being flushed down the toilet.

“Using embryo from stem cell line to prolong other people’s lives is a better use than throwing away embryo in first place,” said Emily Fabrizio-Stover ’18, who also works in the Grabel Lab.

Grabel then provided a brief history of stem cell research policy throughout the last three presidential administrations. In 2001, The Bush Administration established that funding from the National Institute of Health could only be used for embryonic stem cell research if the research was conducted on embryonic stem cell lines isolated prior to Aug. 14, 2001. The Administration restricted federal funding for stem cell research so that they would not be responsible for the generation of any new embryonic stem cells.

Around that time, only a dozen good cell lines had been isolated. This created a challenge for researchers that relied on government funding, as they were attempting to use stem cells as therapies. As a result of this change in policy, researchers had to rely on private funding to develop new stem cell lines.

Grabel does not know what will happen during the Trump Administration. However, she did note that a number of states are currently attempting to establish the fertilized egg as a person in order to make reproductive technology illegal.

“There should be more government funding available for stem cells because stem research is such a huge future field and it is important to invest in it,” Fabrizio-Stover said. “More investment means faster progress, which means people can help people faster.”

This article was amended to clarify the Bush Administration’s stem cell research policy.

Leila Etemad can be reached at letemad@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply