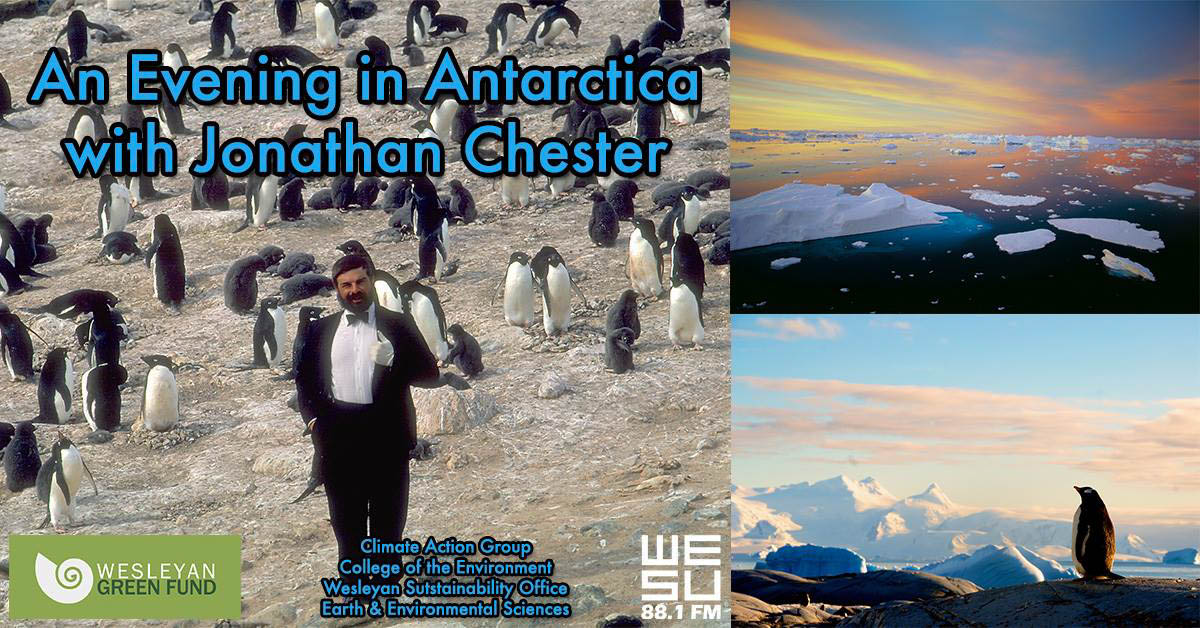

Jonathan Chester, a photographer, environmentalist, climber, and father of Cormac Chester ’20, shared stories from his life and work on Friday, April 13 in Shanklin Hall. The event, entitled “An Evening in Antarctica with Jonathan Chester,” was sponsored by the Green Fund, WESU, Climate Action Group, the Wesleyan Sustainability Office, the College of the Environment, and Earth and Environmental Sciences department.

Chester has extensive experience shooting in the Arctic, the Antarctic, and the Himalayas, experience which has enabled him to write and contribute to 14 books including “Going to Extremes: Project Blizzard and Australia’s Antarctic Heritage,” “The Himalayan Experience,” “Antarctica: Beauty in the Extreme,” and many more.

However, as Chester explained, he hadn’t planned on being an author or a photographer. As a young man, he was passionate about climbing and the outdoors, and soon realized that by becoming a photographer, he could make a living doing what he loved.

“[By] being a photographer, I could still do what I wanted to do in the mountains,” Chester said in an interview with The Argus. “I had to work a bit harder, and be more inventive and creative, and [spend] a lot of time outside writing stories and promoting the photographs and writing books. It’s a great means to an end but it’s also a great end in itself….The creative process that I discovered in sharing stories and having those adventures and being able to entertain and educate people made it all worthwhile.”

Chester’s lecture covered a lot of ground; he gave an overview of the history of Antarctic exploration (all 200 years of it), discussed the research being conducted at the various Antarctic bases and described his experience as a photographer and guide of the uninhabited continent.

The Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1959, ensured that no country could claim territorial sovereignty on the continent, that it would be used for solely peaceful purposes, and that it would continue to host international scientific research. Chester lauded the treaty as an example of successful international cooperation; it turned the continent into a protected wilderness, where science is the only currency of power. And, as Chester explained, research in the Antarctic is important. Ice cores dating back 400,000 and in some cases 800,000 years have enabled scientists to gather extensive data on the history of the earth’s climate.

“But nowhere in that 400,000 or 800,000-year record has there been a time when CO2 levels got above 300 parts per million—now we are at 408,” Chester said. “By doing that scientific research in Antarctica and looking at what the baseline of the world has been for hundreds of thousands of years, even up to a million years, we can realize that this isn’t a normal cycle, this isn’t a natural part of the earth’s fluctuation. We’re going way outside the boundaries of what the earth has been doing without human influence.”

The earth’s changing climate is visible in virtually every facet of the Antarctic environment, from the decreasing krill population to the melting sea ice to the ever-expanding areas with vegetation. Chester presented two approaches by which institutions have tried to address crisis.

“In terms of dealing with Antarctica, we either have to adapt to the fact that the world is changing, or try and slow down the changes,” he said. “As a nation, America is lagging in its attempts to avoid the build-up of CO2, but we’re not doing a very good job of adapting either.”

Chester hopes that through his work as an Antarctic guide and a photographer, he will increase awareness of how climate change is affecting the region and encourage people to modify their behavior to live more sustainably.

This past January, Chester had the chance to bring his family to the continent where he has been traveling and working for decades. It was a lifelong goal of his to show his children, Cormac and Katharine, what had been driving him for so many years.

“It was a way of sharing something that had been an important part of my life for many years that [Cormac] hadn’t really understood anywhere near to the same degree,” he said. “Cormac was giving talks on penguins before he ever saw a penguin—”

“I gave a talk once to a group of kindergartners!” Cormac protested from across the room.

“—And so for him to actually start seeing whales and seals and penguins…[it] was exciting for me to see him so blown away by stuff that…I get blown away every time I go too. It doesn’t get old. You have a sense that some of it might not be there the next time around.”

While Chester’s passion for photography and its role in environmentalism is strong, he also emphasized the importance of being present to understand and appreciate nature. As a guide of adventure cruises in the Antarctic, he hopes people will document their journeys with photographs, but he also tries to ensure that they take time to simply experience the vast beauty of the Antarctic.

“Sometimes we encourage people to put their cameras away and just sit there,” he said. “If you’re taking photographs [all the time], sometimes you don’t appreciate the sounds of silence….We’ll get out somewhere and sometimes we’ll turn the engine off and say ‘Just all sit there, no one take any photographs, don’t talk and just listen,’ and you can hear the ice melting, because there’s air trapped in the ice from the glaciers.”

Some have criticized the tourism industry in the Antarctic for being frivolous and counterproductive as it demands money and resources. But Chester believes that tourism actually supports scientific research and spreads awareness about how the continent is changing.

“We think of ourselves as creating ambassadors for Antarctica when we take people,” Chester explained. “We end a lot of our presentations [by] saying ‘you need to go home; you need to call your politicians. If you care about Antarctica and you want to see it preserved and have the opportunity for future generations to experience this, you need become an activist, become a person who supports the changes that need to be made in our policies of how we consume fossil fuels and use energy and produce energy because it is impacting Antarctica.’ Everything we do here impacts down there in a magnified way.”

Chester recently led Bill Gates and his family on an expedition to the Antarctic. Chester hopes that when people of power and influence see the important work taking place below the Antarctic circle, they will be inspired to support the continued funding of Antarctic research. Chester worked hard to ensure Gates’ experience of the continent was a positive one, and enjoyed spending time with him and his family.

“He is, I think, one of the greatest humanitarians we know in this current day and age. He has used his great intellect and wealth for public good in public health and it was a delight to have him and his family there,” Chester said. “I worked very hard to give them a very safe positive experience. I mean we had a movie night, you know there were just six of us eating popcorn and watching Forrest Gump with Bill Gates and his family. It was a real treat.”

Sasha Cohen can be reached at srcohen@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply