Dani Smotrich-Barr, Photo Editor

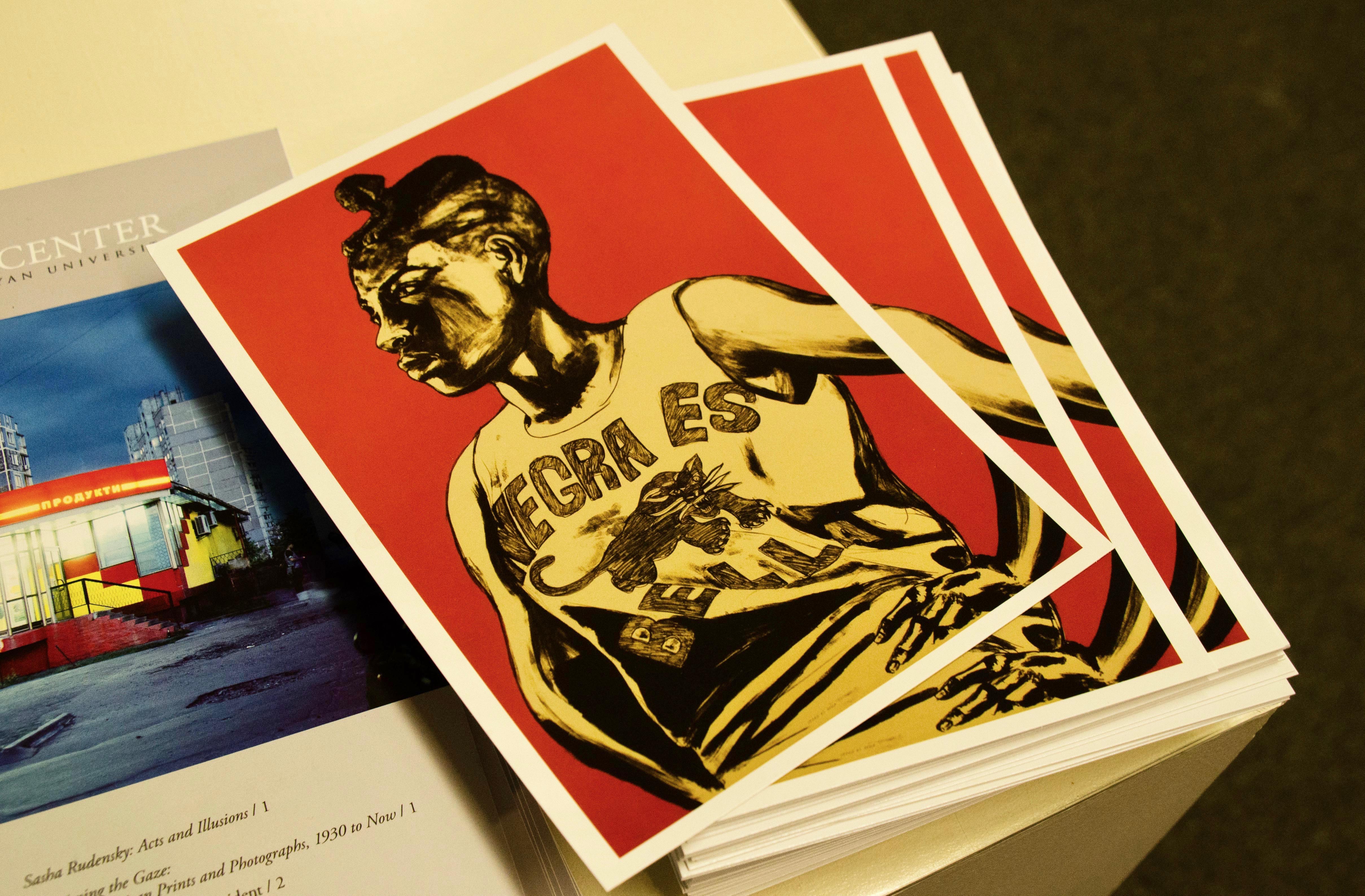

The intrepid souls who braved Wednesday’s miserable weather to attend the opening of the Davison Art Center’s latest exhibition were rewarded with a moving and unique artistic experience. “Reclaiming the Gaze,” an exhibition of photographs and prints created by Black artists from 1930 onwards, was curated by students in Professor of Art History Peter Mark’s class “Advanced Themes in 20th Century Afro-American Art” offered in the Spring 2017 semester. The students spent an entire semester discussing and carefully selecting 39 works from the Davison Art Center’s substantial collection, and the fruits of their labor are finally on display.

The exhibition was introduced by Mark, who supervised the class that put the exhibition together, and Rielly Wieners ’18, one of the students in the class. Wieners, who spoke first, described her experiences in the class and explained the process she and her classmates went through in selecting artwork.

“I expected it to be like every other art history class I’d taken thus far,” Wieners said, describing the day she walked into Mark’s class. “Instead, my fellow classmates and I were greeted by a towering wall of precariously piled notebooks, overstuffed folders, and manila envelopes bursting at the seams, begging to be investigated…there was no syllabus, no formal assignments, no required tests.”

Instead, Wieners and her classmates spent the semester looking at hundreds of works by Black artists in the 20th century, as well as Mark’s personal collection of exhibition posters, catalogues, interviews, and correspondences with various artists.

“We were asked to put the works in conversation with one another, which revealed complex and often competing articulations of intersectional facets of Black culture, identity, and experience in America,” said Wieners of the students’ efforts to create a cohesive collection. “The more we analyzed and the more we researched the more in-depth and complex our discussions became. Spanning across almost 90 years of African American artwork, from the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s to the activism of the ’50s and ’60s Civil Rights movement, to Black Lives Matter, our art historical journey transcended the constraints of time and space.”

“One of the things that is clear is that when you take 39 works of art and put them together the result is more than the sum of its parts,” said Professor Mark, who spoke after Wieners. “Likewise with that seminar what [the students] created was certainly more than the broad ingredients that this professor could provide.”

Mark offered commentary on several specific works and anecdotes about their artists.

“When I first came to African art it was widely stated…that there were three dominant personalities in the art scene…Romare Bearden, Jake Lawrence, and Vince Smith,” said Mark, gesturing to the wall adjacent to the exhibition’s entrance, which contained a print by each of these artists (“Pilate” by Bearden, “Jonkonnu Festival” by Smith, and “Workshop” by Lawrence).

He went on to discuss and compare their works, mentioning Bearden’s bright, blocky shapes and collage-like style, Lawrence’s defined structure and exaggerated perspective, and Smith’s energetic use of color and line.

Mark and Wieners also discussed the logistical aspects of curating an exhibition beyond merely selecting the artwork. In particular, they addressed the challenges of deciding how the works should be laid out in the gallery.

“That was maybe one of the most enlightening or difficult transitions for us was the moment we had to get into planning it in an architectural space,” commented Mark.

“It was definitely painstaking,” agreed Wieners. “We really came in here and then we all had to collaborate and kind of fight it out for which walls were gonna be whose”

Their efforts clearly paid off, as the exhibition is carefully and thoughtfully arranged. One entire wall is empty save for a single long row of lithographs from a series called “Runaways,” by Glenn Ligon ’82. Each of the ten prints contains a paragraph of text by one of Ligon’s friends, who were asked to describe him, paired with a historical illustration relating to slavery in some way. The resulting prints and their visual layout reference runaway slave advertisements, as well as modern-day missing person reports, placing Ligon’s personal identity as a Black man in the greater historical context of slavery.

Another wall with an equally striking layout features an enormous, brightly colored self-portrait by Lyle Ashton Harris ’88 flanked by smaller black-and-white photos by Gordon Parks and Ernest C. Withers. The central photo, titled “Saint Michael Stewart,” features the artist himself, dressed in a police officer’s uniform and gazing defiantly at the camera. The title of the work and the police uniform reference the death of Michael Stewart, a Black graffiti artist who was killed in the custody of the New York City Transit Police. The photos on either side of “Saint Michael Stewart” depict events from the Civil Rights movement: Stokely Carmichael speaking at a protest, a sanitation workers’ strike, Martin Luther King Jr. being confronted by police officers, and members of the Little Rock Nine. Viewed as a whole, the photos on this wall provide commentary on the long history of institutional violence inflicted on African Americans, both in the 1960s and today.

Overall, “Reclaiming the Gaze” is a beautiful and thoughtfully curated look at African-American artwork of the past several decades, much of which has been dangerously under-appreciated by the mainstream artistic establishment.

“Most of these artists, especially the older ones, toiled far from the limelight, without deserved recognition,” Mark said. “I am proud to have helped bring some of these works into the light of day.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.