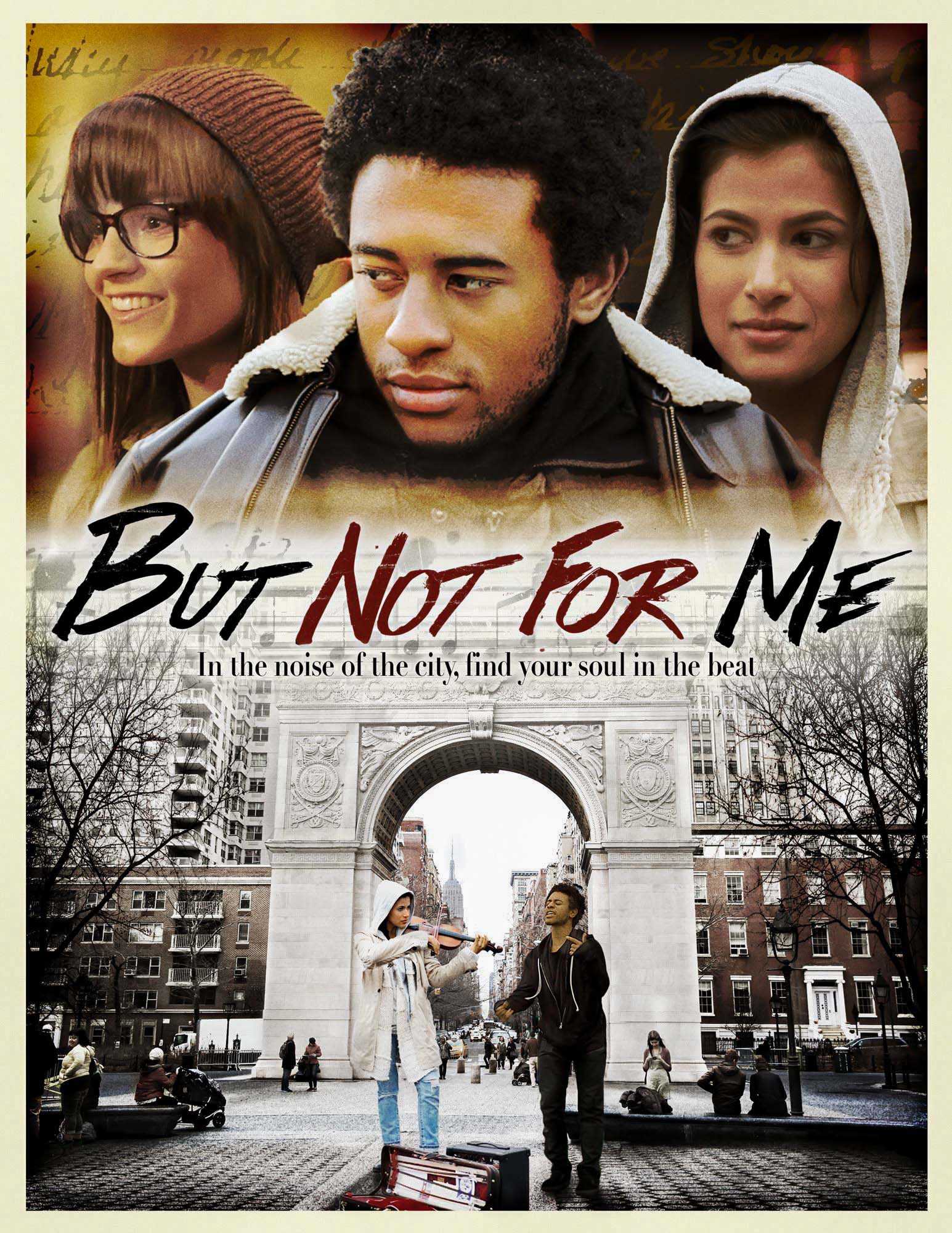

Last Sunday, April 10, Ryan Carmichael and Jason Stefaniak came to campus to screen their debut feature film entitled “But Not For Me” with the help of Ladies First and Cardinal Pictures. Carmichael and Stefaniak met in NYU’s graduate film program, and went on to found the New York-based Impolite Company.

Their production company explores the idea that great art needs to address issues that are not conventionally considered polite to help broaden a person’s way of thinking and change how they experience their daily lives. After the screening, Carmichael and Stefaniak stayed to answer questions about everything from questions about their company to the value of the humanities in filmmaking.

“I think Wesleyan definitely has students who are passionate and want to be involved in film and I wanted to give them the opportunity to hear from people who are definitely in the game and are growing continuously and have had some experience and knowledge and are able to say ‘Here’s what I’ve done and contributed and here’s what it looks like,’” one of the organizers of the event Giselle Lawrence ’18 said. “It was really me reaching out to Cardinal Pictures, and particularly Ladies First reaching out to Cardinal Pictures, as an opportunity for students to come in.”

“But Not For Me” follows the story of Will, an aspiring artist who works as a copywriter to pay the bills in New York. He struggles with his meaningless job and his failure at accomplishing his dreams of being a performer. But when Will meets his new neighbor Hope, he is immediately moved. The two talk about their family, how they define themselves, and their dreams through the wall that separates their rooms. Hope speaks about her grandmother, who taught her to play the violin.

“She believed in the power of music to save the world,” Hope said.

Will begs her to play for him, and she finally agrees. As she plays, he puts a beat to her music and sings along, creating a beautiful and unique combination of classical and modern music. Will asks her to do street performances with him, and Hope reluctantly agrees.

They perform (with wide approval) in the streets of New York. Their stunning combination of hip hop, spoken word, and classical music overlays their intense and intricate relationship. When Will’s dad dies, his unravelling world collapses even more. With this breakdown, Will is forced to merge his dreams of what could be with the reality of what is.

The film further challenges the dichotomy between dreams and reality by introducing an alternate Will as the narrator of the film. This replacement Will is stabbed by a group of unidentifiable men. After the screening, Carmichael addressed this form of self-sabotage and its relevance to the wider film.

“First and foremost, as far as a general layer of the movie is concerned, those scenes were constructed as a postmodernist commentary on the story that’s being told,” Carmichael explained. “You have the opening narration, which is like, ‘I’m going to tell you the story.’ That’s where we get that out of the way initially. [Will]’s always referencing back to the fact that a story is being told. When we get to the part where he’s being stabbed, he’s saying, ‘Well, I’m a narrator, and as the narrator my job is to keep order.’ But there can’t be order when someone loves unrequitedly.”

In the end, Hope moves out of the neighboring room with a new man, leaving Will with an unsatisfying goodbye and more confusion. He is forced to conform his desire to change the world to the necessity of getting a job that pays the bills and dealing with real and complicated relationships. His beliefs are constantly challenged and defied, and “But Not For Me” follows his struggle to find happiness and define the meaning and purpose of art in a convoluted world.

After the screening, Carmichael and Stefaniak answered questions about how they met, the creation of Impolite Company, and the technicalities of production. When asked how they funded “But Not For Me,” they laughed.

Stefaniak addressed the question, saying that they started a Kickstarter campaign with an $100,000 goal, knowing that they probably wouldn’t reach it. The campaign gave them some press coverage, and soon, a woman to whom Stefaniak had once sold a fan contacted them, harboring an interest in their project. After some communication, they met with her in person.

“She said to us, ‘How much money do you need to make the film?’” Stefaniak explained. “I said, ‘$100,000?’ And she said, ‘Okay!’”

In the discussion that followed, Carmichael and Stefaniak shared the difficulties and rewards that came with their ongoing search for success in the film world. In a way, their journey mirrors Will’s pursuit for meaning in art.

“People will listen to you. And while they’re doing that, let me give them something to think about,” Will begs Hope, echoing Carmichael and Stefaniak’s attempt to make people think about our own societal problems.

Leave a Reply