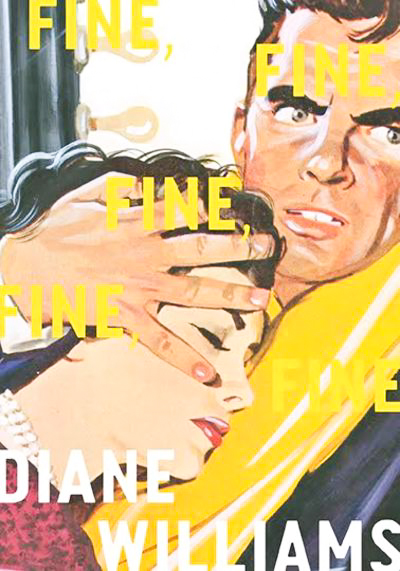

Flash fiction and a college schedule go well together. Most students lament that they have no time to read for pleasure, and reasonably so—coupled with essays, problem sets, extracurriculars, friends, sports, and, of course, assigned readings, pleasure reading seems like an unattainable hobby. But most of the time, these students are thinking about novels and essay collections; they are thinking about long-form books that require wide stretches of time to complete. But not all pleasure reading has to be this way—some can be exceedingly short, requiring no more than five minutes to get through. Enter Diane Williams’s new collection of stories, “Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine,” a flash fiction collection that somehow holds 40 different stories in 131 pages. No single piece exceeds 1,000 words; some occupy only one paragraph. Regardless of page count, though, every story shares a loose commonality, not necessarily in subject matter but in the sheer feeling you get from reading them—at a fundamental level, every single one of them is, in the words of Jonathan Franzen, “very, very weird.”

Diane Williams is the founder and editor of the literary annual called “NOON,” which Rachel Symes of the New York Times has described as a “beautiful annual that remains staunchly avant-garde in its commitment to work that is oblique, enigmatic and impossible to ignore.”

Williams’s new collection reflects her tastes, as each story maintains a total weirdness that is most definitely unignorable.

Take “The Skol,” a story late in the collection that reads: “In the ocean, Mrs. Clavey decided to advance on foot at shoulder-high depth. A tiny swallow of water coincided with her deliberation. It tasted like a cold, salted variety of her favorite payang congou tea. She didn’t intend to drink more, but she did drink—more.”

That’s the whole story. What is Williams getting at here? Is it something about the parallelism between people and ocean? Or something about force and drowning? And that mention of “payang congou tea”, and the last m-dash—these odd details add to the enigmatic creature that seems to be coming at you while reading this piece, a creature that is enticing, terrifying, and fundamentally indescribable.

If there is at all some kind of thematic string that runs through each of these stories, it’s probably how ubiquitous death can be. One of the most poignant pieces, “A Gray Pottery Head,” begins with a woman examining a sculpted head in her home. It then jumps to the woman getting in a car crash, and a police officer examining her body. Williams wants to show her readers that death is all around us, in the lifeless head of both the sculpture and the woman. Her talent, of course, lies in making this kind of point in less than three pages—when the point does come at you, it’s like getting hit with a paintball: it doesn’t hurt too much, but the pain is both acute and lasting.

Because of the strong avant-garde feeling in “Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine,” many stories are frustrating and seemingly impossible to penetrate. Other stories, however, are exhilarating. In the end, there seems to be an element of chance whether a story will grab you or not—and if it doesn’t in the first few lines, you will be absolutely lost.

In my own experience, it was split close to fifty-fifty in terms of frustration versus exhilaration. Each piece requires a couple reads, and with some they just seem to get weirder and weirder each time around. In truth, every story in Williams’s collection is an experiment with structure, form, and subject. And like any experiment, some are doomed to fail while others come out triumphant. “Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine” has elements of both, and they switch off throughout—sometimes a story’s light comes on and reveals something you have never seen before, and sometimes the room simply stays dark.

The most obvious literary connection to make would be to Lydia Davis, who has quietly and beautifully championed the one-page-story form in the last few years. But Williams seems to be doing something far harsher in each story. While Lydia Davis’s pieces make you chuckle with their cleverness and think with their poignancy, Williams’s pieces don’t want you to get that comfortable.

“Fine, Fine, Fine Fine, Fine” feels less like a creation and more like some kind of violation—it violates the way you think about sentences, stories, and essentially how the world works. And again, all of this violation happens in the span of a few pages, most likely in the midst of your college schedule—it happens when you’re waiting to meet a friend, when you sit down between classes, when you lie down before sleeping.

Leave a Reply