Many of the problems President Victor Butterfield faced during his tenure from 1943 to 1967 remain in only slightly different incarnations half a century later. One such problem is that of the inclusivity of Greek Life, specifically that of the University’s fraternities, which were all white and Christian as the 1960s approached.

In his history of the University, David Potts dedicates significant space to Butterfield, with three full columns of the index dedicated to the former President. On fraternities, Potts traces the series of developments, or lackthereof, that defined Butterfield’s relationship with fraternity members and more importantly the rest of the student body, many of whom were not allowed to join Wesleyan fraternities either because they were non-white or Jewish, for example.

In the late 1950s, 85 percent of undergraduates belonged to a fraternity, and 40 percent lived in one of the dozen fraternity houses on campus. To put that in perspective, consider the backlash of co-educating fraternities at Wesleyan over the last few years, where today 15 percent of the student population is involved in Greek Life on campus. By gender identity, 21 percent of the male-identifying population are involved in Greek Life compared to 6 percent of the female-identifying population. Whereas today being involved in Greek Life is the exception to the social rule at the University, the inverse was true during Butterfield’s era.

Close to 90 percent of students relied on fraternity eating clubs for meal services. For this reason, fraternities and their privately owned houses provided significant savings to the University financially, thus giving the administration an incentive to sustain Greek Life on campus. This incentive is not far off from the financial advantages that Greek Life has provided the University with more recently in terms of donations, and Buttefield, much like President Roth, had to confront an apparent conflict of interest when seeking to reform fraternities.

As Potts puts it, “The most glaring ethical problem posed by Wesleyan’s fraternity system was lingering discrimination against African Americans and Jews in several houses. Butterfield held throughout the decade [1950s] to his belief in letting students take the needed ‘responsibility and initiative’ based on ‘convictions of conscience’ to resolve the issue of restrictive membership clauses or initiation rituals.” At Amherst and Williams, for example, administrations had intervened in Greek Life to break down discriminatory barriers while many of Wesleyan’s fraternities remained closed to Jews and non-white students. Butterfield’s patience with discriminatory fraternities was supported by students in 1957, according to Potts. However, five years had passed at that point since the first three fraternities admitted black students, while other residential fraternities had not followed suit.

“Students saw Wesleyan lag behind Amherst and Williams, where discrimination clauses were gone by 1954,” Potts wrote. “A year later the College Senate [now the Wesleyan Student Assembly] resolved that the houses where national stipulations sustained bias against African Americans or Jews needed to take action. They must gain reform from within the national organizations or disaffiliate from them. In 1958 the trustees, president, and faculty members clearly stated their disapproval of exclusionary practices.”

These key steps by students and University actors resulted in a change in public opinion at the University by 1958, with one survey indicating that, when told in advance, about a quarter of the freshman class said that they would not join a house with membership restrictions. Then, three houses severed their national affiliations in 1959 and became local fraternities with new names.

According to Potts, The Argus praised Butterfield’s role in ending racial discrimination at fraternities, and announced an end to “formal discrimination” at Wesleyan in 1959. Two years later, Delta Tau Delta became the last chapter on campus to initiate its “first person of the Jewish faith.” By 1963, DTD and seven others, beginning with Eclectic in 1950, had initiated their first black pledge.

Potts also broadens his history out to how Wesleyan’s struggles with race relations in Greek Life correlated to race relations at the University and in the United States at the time.

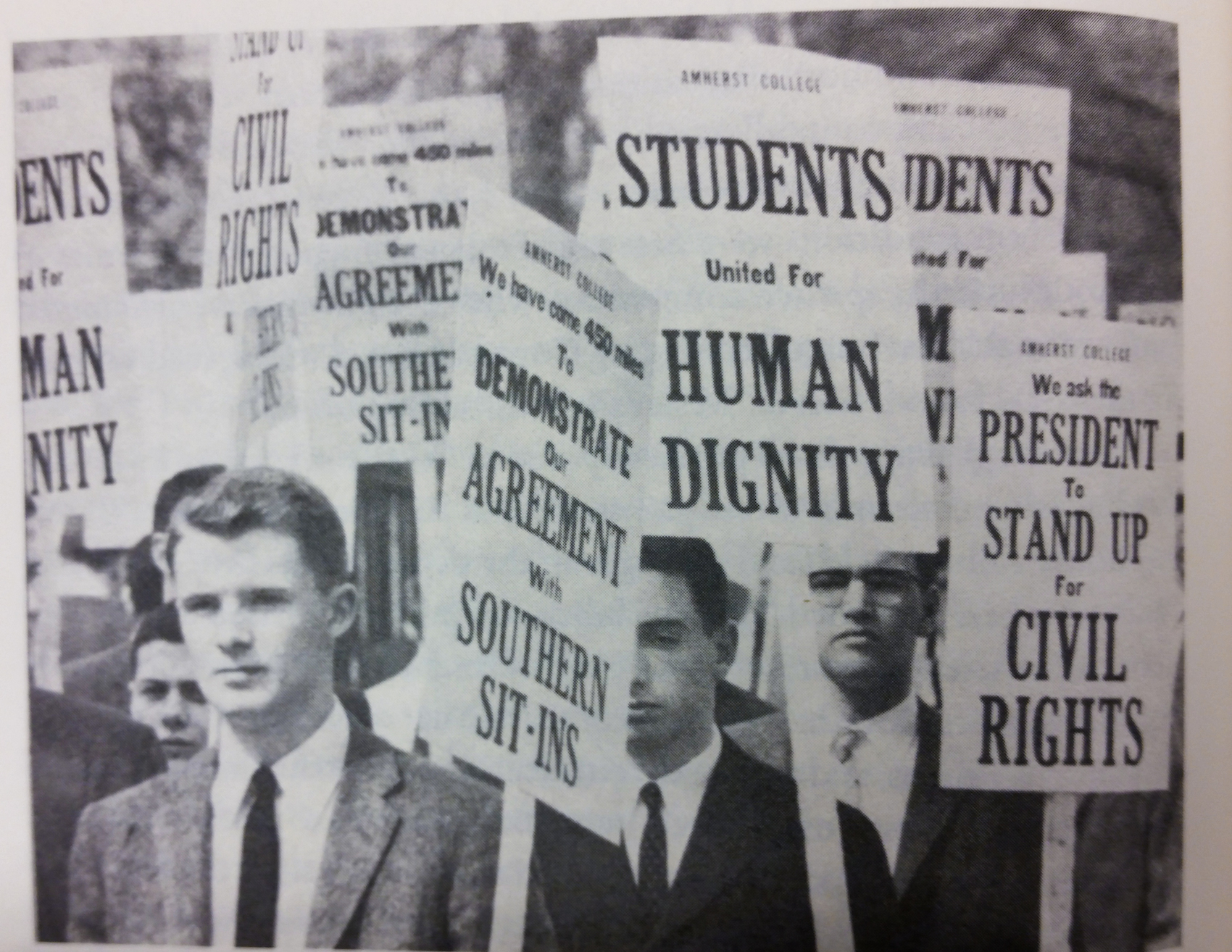

“Initiatives to reform the fraternities helped foster a morals-based activism that students could apply in the late 1950s to race relations on the national level,” Potts wrote. “Occasional Argus attention earlier in the decade to racial issues on campus and in Middletown broadened in 1956 to address segregation issues in the South. Black student sit-ins at Southern lunch counters in early 1960 moved groups of Wesleyan students from discussion to action. In March the Wesleyan committee on Civil Rights formed to raise scholarship funds for the demonstrators at sit-ins.”

In an example of student activism spilling over campus borders into Middletown, solicitations for the fund came on Main Street, where 250 students and 30 faculty members participated. A month later, five University students joined students at Williams, Amherst, and Trinity for a “coat and tie” march outside the White House to protest against racial segregation in the south. In May 1961, religion department faculty members David E. Swift and John D. Maguire joined with colleagues from Yale in one of the early Freedom Rides designed to challenge the Jim Crow laws that denied equal access in public interstate transportation facilities. They were arrested and jailed in Montgomery, Alabama.

Then, that winter, students packed the Memorial Chapel to hear Martin Luther King Jr. preach. One month later, once again in the chapel, they listened to Malcolm X promote a separatist pathway to racial justice.

As ugly as the University’s past with fraternities may be, the reform that students first engaged with, along with President Butterfield and faculty members, moved the University toward the activism that it became known for during the Civil Rights Era. Though many students argue that there is much progress to be made at the University regarding race relations and equity and inclusion, one can only hope that similar activism on campus will spill over Broad Street toward the rest of America and the world.

Leave a Reply