Blood Meridian: “Bone Tomahawk” mashes genres with reckless abandon.

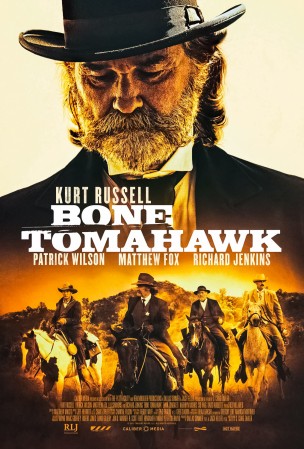

“Bone Tomahawk,” the directorial debut by novelist S. Craig Zahler, is a nasty and spry little piece of genre filmmaking. The film, which stars Kurt Russell, Matthew Fox, Patrick Wilson, and Richard Jenkins manages to be both brutal and contemplative, carefully moving through its 132-minute runtime with a series of painstakingly calibrated moments of moody tension. It’s rare to see a horror western of any kind, and even rarer that one might attract the caliber of talent on display in “Bone Tomahawk.” Luckily, Zahler’s picture refuses to waste its actors or the gleeful madness of its premise, barreling forward with a level of devil-may-care confidence that other filmmakers might take multiple features to achieve.

Playing as a sort of hybrid of “The Hills Have Eyes” and “The Searchers,” “Bone Tomahawk” opens on a pair of highway robbers who find themselves hunted by a mysterious frontier presence. These troglodytes quickly dispatch one of their prey and send the other screaming to the nearest town, unaware that his stalker is still on his heels. The robber is intercepted by law enforcement on the edge of Bright Hope, where after a short scuffle with Sheriff Franklin Hunt (Russell) he receives medical treatment from the doctor’s assistant (Lili Simmons), whose cowboy husband (Wilson) has been laid up with a broken leg. That night, having caught up with their prey, the troglodytes descend on Bright Hope, slaughter the robber and kidnap the doctor’s assistant. The next morning Sheriff Hunt, the injured cowboy Arthur O’Dwyer, bumbling deputy Chicory (Jenkins), and a local gunslinger (Fox) resolve to head out in pursuit, and to kill the cave dwelling cannibals that have made off with one of their own.

More so than one might expect from a film in which cowboys must do battle with flesh eaters, “Bone Tomahawk” is a masterclass in subtle tension. Even in its opening sequence, the film takes its time to reveal its central scourge, and once it reaches the streets of Bright Hope, Zahler’s picture makes sure to carefully establish each of his characters before diving back into the action. In fact, much of the film is made up of the characters simply talking, revealing their insecurities and desires on the road to their hunt. For quite a while, “Bone Tomahawk” is willing to almost completely hide its horror roots, having so much fun with the lush iconography of the Hollywood Western that those upcoming scares might almost seem secondary. When those scares do arrive, however, Zahler refuses to hold back. Making fantastic use of the frontier landscape, the director turns the crags and caverns of the desert into a moody and vibrant killing field. Obscuring his antagonists through massive compositions rather than ugly quick cuts, the filmmaker manages to obfuscate without confusing his audience. Even once the picture becomes more ostentatiously horror, it still holds on to the western inclinations of its first two thirds. It dwarfs its actors against the pitiless landscape and achieves both the sort of atmospheric terror and epic scale that set apart films as diverse as “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” and “Stagecoach.”

The result is a film that’s both smarter and more unsettling than one might initially expect. The use of grindhouse elements plays as a not-so-subtle commentary on the deep racism of films like “The Searchers,” while the wide unknown span on the picture’s cinematography enhances its building tension. That “Bone Tomahawk” manages to succeed as both a western and a horror film is something of a small miracle, no doubt achieved as a result of the film’s willingness to simply commit to everything on screen. As much as Zahler’s picture wants to play with convention and with expectations, its subversions never feel aggressively tongue-in-cheek. Even as “Bone Tomahawk” levels sharp criticism against its parent genres, it also celebrates and reexamines what allowed those films to work to begin with. Since the western and the horror film have both undergone such extended periods of revisionism, Zahler understands that he needs to strike at something visceral with his own picture to make “Bone Tomahawk” more than a simple gonzo mashup. Through extended character work, an eagle-eyed attention to tone, and a carefully realized world, he does just that. The result is a film that both feels completely at home in the generic landscapes it engages with, while remaining singular. If you want to watch “Bone Tomahawk,” there’s no other film you can watch instead.

That a film like this makes room for the sort of performances that Wilson, Russell, and Fox turn in is also quite miraculous. Far from a collection of stereotypes or tropes, each character is given a clear and organic arc that stands out even amongst the third act’s gruesome action. With each subsequent film, Kurt Russell is revealing himself to be a more and more nuanced craftsman, one with the power to imbue roles that don’t automatically scream “depth” with the sort of nuance and lived-in quality that audiences expect from prestige actors alone. Even at 64, he’s a fearlessly physical actor who wears his weary gruffness without a smidge of self-consciousness or cliche. Where his sheriff might threaten to become a flaccid archetype by way of Eastwood’s Bill Munny, Russell injects the role with the sort of wicked humor that other westerns might try desperately to avoid. He magnifies the work he did as the legendary Wyatt Earp in 1993’s “Tombstone,” painting a lawman who is both a part of the western tradition and ever-so-perfectly tweaked beyond it. Even as he convincingly embodies a life of loneliness and violence on the frontier, Russell still remains Carpenter’s boy at heart, a cocky and sly agent of chaos.

This year has been a fantastic one for genre filmmaking, and in many ways “Bone Tomahawk” is a crowning achievement: an unabashedly wild piece of cinema that demands both to be taken seriously and to have its run of the landscape, free to populate the world with the craziest of terrors and the strangest of set pieces. By simultaneously embracing and rebuking its parentage, Zahler’s debut allows itself to flower in new and familiar ways that make room for beauty, horror, and humor. “Bone Tomahawk” is not here to shock or appall, but it’s also not looking to simply appease expectations. Above all else, this is a film that is content to simply be itself, and to do so with the rare and explosive confidence that few films have the guts to wear anymore.

Comments are closed