The biopic, a film about a historical event or person, is one of Hollywood’s oldest and most heavily scrutinized subgenres. “Steve Jobs,” written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Danny Boyle, has been widely criticized for “historical inaccuracies,” with many saying the dialogue is inaccurate and the events portrayed in the film didn’t happen in reality. These arguments are a waste of time.

Historical inaccuracy, including both factual truth and how people or events are represented, is the main criticism launched at biopics. While critics praised Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” as a tour de force film, many chastised it for screenwriter Tony Kushner’s decision to have representatives from Connecticut vote against the bill to abolish slavery. In reality, they voted for the bill. Similar controversy erupted over the Ben Affleck directed “Argo,” which won the Oscar Award for Best Picture. It was denounced for its inaccurate portrayal of Canada’s role in the evacuation of six government officials in Tehran, Iran, and the absurd lack of realism in its airport climax. These are only a few recent examples of biopics coming under intense scrutiny that has little to do with a film’s artistic quality.

But why should we hold Hollywood to the same standards as our textbooks? A film is a work of fiction, even if it is based on or inspired by real-life events. Film is not a means of portraying a realistic view of history, but rather, of entertaining audiences and informing them of the broad strokes of an event or person. Was it the job of Spielberg to accurately recite exactly what happened during Lincoln’s final year? No. Nor was it the job of Affleck to make everyone look good. Their job was to create memorable movies that interested people in history, not to give them an actual history lesson.

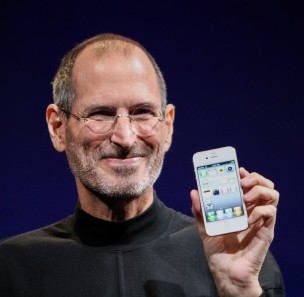

Moreover, creative freedom is essential to the creation of great movies. Sure, the airport scene in “Argo” was absurd, but who could deny that it put them on the edge of their seats? Was it offensive that Canada was not given proper credit? Of course, and people have every right to complain. But it ratcheted up the already high stakes of the film, making the situation of the six hiding in Tehran even more desperate. If the sole or primary purpose of “Argo,” “Lincoln,” or any other biopic was to enforce a person or group’s good reputation, than the biopic genre would be horrible. One need not look any further than “Jobs,” the first Steve Jobs biopic with Ashton Kutcher in the title role. Yes, his casting was a mistake, but the bigger mistake was attempting to portray him in the most positive light possible. Portraying any character as perfect is always tedious, hence the need to be critical of them, and the need for artists to have the freedom to do so.

This is not to suggest that creative freedom guarantees successful filmmaking. There are no formulas or rules that govern the quality of a film. But this is, conversely, why a film needs creative freedom. Art does not have the equivalent of a scientific method, nor a precise means of crafting a film or work of art. There are merely techniques and budgetary requirements that allow people to create movies. It is the job of the artist, using some and other broad restrictions that I have outlined above, to create something beautiful that cannot be fully rationalized. Increased restrictions, including (but not limited to) those that are typically placed on biopics, such as the need to be entirely accurate or properly represent people, make it more difficult for an artist to succeed.

“Steve Jobs” is a prime example of why creative freedom is more important than historical accuracy. Sorkin himself has admitted that his film is inaccurate, telling an audience at the film’s premier at the London Film Festival, “Steve Jobs did not, as far as I know, have confrontations with the same six people 40 minutes before every product launch. That is plainly a writer’s conceit. But I do think the movie gets at some larger truths.” Steve Wozniak, Apple co-founder (played by Seth Rogen in the film), has also stated that his character’s dialogue is inaccurate. “I don’t talk that way…The lines I heard spoken were not things that I would say but carried the right message, at least partially.” While the dialogue and plot is inaccurate, of course, it captures the emotion and spirit of the real people being portrayed. In many ways, this is what a film’s goals should be: after all, it is a work of art, meant to capture emotions rather than merely educate.

Furthermore, if it were the job of a movie to be an entirely accurate representation of reality, we would be missing out on the tremendous beauty of Sorkin’s writing. Of course the dialogue in “Steve Jobs” is unrealistic: who on earth could actually speak that fast? But, instead of absolute adherence to reality, we get something deeper, and more poetic. Sorkin uses the persona, not precise reality, of Steve Jobs to explore what it means to be an influential genius, on both an intellectual and emotional level. Jobs (the film version, portrayed by Michael Fassbender) is a Machiavellian genius, and an emotionally aloof backstabber. A film that sticks strictly to historical accuracy could perhaps portray the former idea fairly well, but only with the creative freedom of film could we understand the internal pain of a great historical figure. A history textbook couldn’t possibly do that. So, why is it more important to make a movie version of a textbook than make a good movie?

Look, understanding history is an important thing. But that doesn’t mean that it should restrict the freedom of film.

Leave a Reply