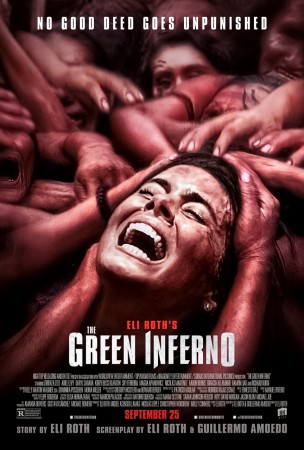

Eli Roth's latest endeavor makes cannibalism toothless.

It’s probably fair to say that no one will be watching Eli Roth’s “The Green Inferno” for highbrow entertainment. The picture, which takes its inspiration from films such as Ruggero Deodato’s notorious “Cannibal Holocaust” and Umberto Lenzi’s “Make Them Die Slowly” (and its title from the meta-documentary within Deodato’s film) is an homage to the cannibal exploitation flicks of the 1970s and 1980s. The film wears its inspirations on its sleeve. It’s a spastic, gruesome little film designed to appeal to a very specific set of aesthetics, and it does very little to dredge outside of that pond. Unfortunately for Roth, “Inferno” manages to capture very little of what energized its source material, replacing Deodato and Lenzi’s gleeful savagery with something closer to outright contempt, and rarely even delivers on the carnage that the director and his idols are best known for. It’s an ugly, gag-inducing trifle, the shocking aspirations of which go relatively underserved.

“Inferno’s” story is simple enough: A collective of New York college activists venture out into the Peruvian Amazon in hopes of protesting widespread deforestation, which threatens to wipe out a number of rarely seen indigenous peoples who have made their home within the rainforest. Among them is Justine (Lorenza Izzo), who is new to the concept of activism, spurred on by a disturbing classroom lecture on the prevalence of female genital mutilation and a budding crush on the group’s slick, charismatic leader Alejandro (Ariel Levy—but different from the University’s Visiting Professor). The plan is simple and somewhat ill-conceived: The students will chain themselves to trees and equipment during a break in the destruction, so that when the crews return they will be unable to proceed with their work. Additionally, each member of the collective will film the entire ordeal with their cell phones, so that the mercenary militias tasked with overseeing the bulldozing of the treeline will be unable to simply execute the overzealous activists.

The protest itself is a minor success. Exceptionally pleased with themselves, the students are escorted to a small passenger plane by government officials and sent home. Unfortunately, there is an engine malfunction and the aircraft plummets, depositing the group back in the forest and into the clutches of one of those undiscovered tribes they were desperate to protect. To make matters dicier, these people are unrepentant cannibals. Who’da thunk.

Before the plane crash that bisects the plot (and a few of the characters), the activists come across a ripe combination of pretentious, naive, and uninitiated. The horrific punishments that await them, the filmmaker argues, are fair considering how annoying these young adults are and how eager they are to meddle in matters they don’t understand. Satirizing a certain strain of modern activism—the type that sends privileged white college students abroad to take jolly pictures with the suffering children of the world, which they can then display on social media—is an interesting prospect.

Unfortunately, it is a prospect “Inferno” all but entirely miscalculates. Certainly, some of its characters are overbearing and a little presumptuous, but the film very rarely casts them as exploitative in the way that Roth’s commentary during the picture’s press junket would suggest. Knowing what sort of horror they had planned for their characters, the Italian exploitation films on which “Inferno” is based gave their victims galleries some deeply revolting aspirations. In “Cannibal Holocaust,” a group of documentarians use their anthropological expedition as a chance to exact neocolonial violence on the tribes they encounter. In “Make Them Die,” one of the central meals-to-be is a mobster on the lam who similarly abuses the indigenous people he encounters. Both films end with a (unsubtly posed) question: Is there any difference between the groups we deem civilized and those we label as primitive? Hasn’t history shown the former group as even more likely to endorse and commit heinous violence?

There are moments when “The Green Inferno” seems to be attempting this, but the film never makes this clear enough to ease audience’s discomfort with Roth’s gleefully issued death warrants. It also makes the film’s racial politics even dicier than those of its predecessors.

While by no means progressive in the way they characterized Amazonian tribes, Lenzi and Deodato at least attempted to portray the violence enacted against their protagonists as something out of the ordinary, a visceral reaction to the wanton terror waged by these documentarians and tourists. Without a doubt these films got carried away in depicting the creative barbarity of some of the punishments brought down by the tribes, but both end with an attempted suggestion that these natives were good people whose attempts to simply live their lives were horrifically interrupted by those who simply got off on the geopolitical power of watching them suffer.

By failing to give the audience any good reason to really want its characters to suffer, however, “Inferno” ends up making its cannibals look entirely sadistic, a troubling characterization which extends to their design. Roth decorates his natives will all the subtlety of Disney’s “Jungle Cruise,” adorning them with wicked-looking jewelry, menacing full body paint, and the sort of facial piercings that might make Joseph Conrad call bullshit. The director claims that he based the look of the indigenous peoples (who, as opposed to in “Holocaust” go completely unnamed) off of actual tribes, but it’s more likely that he read some old Tintin cartoons and called it a day.

What’s perhaps more surprising than “Inferno’s” failure as a sensitive sociological study is its total failure as a horror movie, or even a splatter film. There’s absolutely zero tension throughout the picture, and very rarely does Roth make the atmosphere of the rainforest feel even slightly foreboding. Despite his professed love for his source material, the director even fails to really replicate the sort of kid-in-a-candy-shop carnage that those films achieved, peaking with one gruesome but unimpressive killing at just about the halfway mark.

One would think that if Roth was so willing to throw sensitivity out the window, he might at least devote the excess energy to creating something appropriately revolting, but each of the deaths after the first is an uncreative mess of quick cuts. This is only complicated by “Inferno’s” strange tonal issues, which introduce moments on gonzo comedy at seemingly random intervals that do little else than interrupt the picture’s already minimal tension. When Roth tries to pull a twist just past the midway point, it fails quite miserably, stoking some cliché infighting for a little while before almost completely fading from memory.

The failure of “Inferno” isn’t exactly surprising. “Cabin Fever” and the “Hostel” films have shown Roth to be a director who salivates over the dark excess of splatter cinema without any understanding of how to execute them well. Still, it’s pretty surprising to see a film that feels so artless, especially in comparison to pictures that made their bones by being shoddy little shrines to intestines over intellect. With all the directions in which he could have taken “The Green Inferno,” who knew that Roth would opt for toothless?

-

weslad