Rather than expanding on her oeuvre, Honeymoon has Elizabeth Grant doubling down on her Lana del Rey persona.

How you feel about Lana del Rey largely depends on what you think Elizabeth Grant’s stage persona stands for and how much that adopted personality can do for you. Far more so than that many other artists, Grant’s music is dependent on her posture and affectation to the degree that, with each successive album, one might wonder whether the things that Grant is singing about under the Lana title are her own feelings or that of the fictional character of Lana. That is to say, how much of Lana del Rey’s retro-glam-ennui are you willing to buy?

This holds especially true of Honeymoon, del Rey’s latest effort. More so than the two previous albums Grant has released under her moniker, Honeymoon reads and listens as a full-fledged endorsement of her stage persona, an absolute immersion into those qualities most commonly attributed to Lana and her music. From the first mournful strings of the album’s title track (which sound as though they’d be perfectly at home in Stephen Sondheim’s “Follies”), the record exists in exactly the world that listeners expect from Lana del Rey. It is orchestral, vintage, and shot through with old world yearning. Gone is the winking of del Rey’s previous effort Ultraviolence, replaced with a straight-faced commitment to the carefully arranged sad girl aesthetic that Grant became known for when Born to Die dropped in 2012.

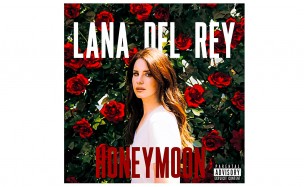

For those who found the carefully applied irony of del Rey’s last album unconvincing, Honeymoon will no doubt be a relief. There is nothing like “Brooklyn Baby” or “Fucked My Way to the Top” to be found here, no sly suggestions that Grant is as aware of how constructed the del Rey personality really is. Instead, the record leans full-tilt into that identity as something absolutely concrete in the world. Nor is Grant coy about this. Look to the LP’s cover art, which depicts Lana in sunhat and face-obscuring sunglasses sitting in the back of a Starline Hollywood tours vehicle. If there is a more Lana image than this, Grant would probably like to know (a cigarette might have been a good addition). The photo functions as an announcement of sorts, a peek into the box to assure the customer of what they’re getting. Perhaps the Lana of Ultraviolence might have drawn attention to the cover’s suggestion that Grant is being shown as little more than a tourist in the world she’s embracing. But the Lana of Honeymoon has memorized the maps of the stars’ homes, taken close notes on the names of all the streets. She’s already stuck her flag into the ground and claimed this place as her own.

In some ways this is one of the record’s greatest strengths. It’s always nice to see an artist fully commit to his or her schtick, and Honeymoon is something of a binding oath between Grant and hers. Without the urge to be ironic or to provide the audience with some sort of knowing escape route, Grant can really sink her teeth into the Lana persona and bask in the West Coast Gothic spirit of her basest aspirations. At its best, Honeymoon becomes a kind of musical “Play it as it Lays,” an affecting nugget of discontent filtered through the sun-kissed lens of the Golden State. There’s the sense throughout, especially on songs like “The Blackest Day,” that Grant has finally mastered that combination of too-cool-for-you apathy and barely concealed desperation that she’s been working so hard to conjure on nearly every song she’s released up to this point. Never has California felt more oppressively autumnal.

Even the record’s more upbeat (or, alternatively, less depressing) tracks descend on the listener with a sort of morose grandeur. “Pink flamingoes always fascinated me/I know what only the girls know/hoes with lies akin to me,” Grant sings on second single “Music to Watch Boys To,” in what might be called Honeymoon’s mission statement. At its best, the album turns the various quirks and obsessions of the del Rey persona into a sort of emotional prison for Lana, one that forces her to prop herself up on symbols and trinkets that do little to help her escape her inner distress. Never is this particular strain clearer than on “High by the Beach,” where the chugging refrain (“All I wanna do is get high by the beach”) suddenly drowns out the tail end of what seems like a plea for help: “I don’t want to do this anymore; it’s so surreal/I can’t survive if this is all that’s real.”

This is not to say that Honeymoon is entirely successful. Clocking in at over an hour, it’s easy for the record’s 14 tracks to blend together, which has the dual drawback of draining the album of much of its energy and allowing some of the more poignant moments toward the back end to go unnoticed. In the end, whether or not the listener deems Honeymoon a triumph for Grant and del Rey, the album marks an end point, signaling that, in all likelihood, the current form that Grant’s music takes has been exhausted.

Despite the best moments on Honeymoon, it would be difficult to argue that Grant (or del Rey) has another album like this in her, that she can continue to do the one thing that she’s been able to do so well so far without it becoming incessant or stifling beyond repair. By removing much of the humor and edge that brought Ultraviolence to life and replacing it with more lavish mopeyness, Grant has ultimately limited del Rey’s emotional range. Certainly, she has proven that she can move quite deftly in the space that she’s allotted for herself, but you still get the sense that that chamber is now very rapidly draining of oxygen.

In many ways, Grant has postured herself as the pop music equivalent of The National, another musical outfit known for their ability to do one sad thing very, very well. However, with The National, there has always been a sense of constant inter-album evolution, such that even when the band returns to familiar territory they’ve only come back to reveal something deeper. Grant, though she has also proven time and time again that she can do her one thing quite adeptly, has yet to really commit to deepening her act. In many ways, it seemed as though she might in the wake of Ultraviolence, which at least slightly reoriented Lana, engaging with something outside of the nom de plume. Honeymoon seems to be a revocation of this, albeit a beautifully produced and often quite engaging one.

Though not quite a regression, it’s certainly a retreat back to a comfort zone that’s well-furnished but slightly too familiar. That’s not to flat-out call Lana del Rey a one-trick pony. It just might be a good idea for her to begin to vary her act.

Comments are closed