“Black Mass” does little to illuminate the mystery of “Whitey” Bulger.

“Black Mass,” directed by Scott Cooper (“Crazy Heart,” “Out of the Furnace”), is a stately film, conspicuous in its ambition and self-regard. It moves forward slowly (at times, glacially) giving each of its scenes room to breathe, to impress themselves on the audience. When the screen isn’t filled with brutal acts of violence, it is preoccupied with meaningful, actorly stares which train themselves on the audience and the other characters with all the weight of one of the picture’s many gun barrels. With all its darkness, distrust for authority, contempt for incompetence, and fascination with evil, Cooper’s film wants to weigh heavy on your heart.

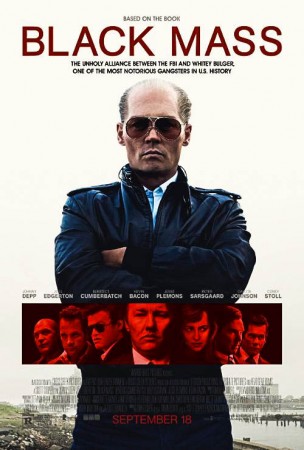

Given its subject matter, that shouldn’t be all that difficult. “Black Mass” tells the story of notorious Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger (Johnny Depp), who was arrested in 2011 after 16 years on the lam. Beginning in 1975, the film primarily focuses on Bulger’s time as an FBI informant and his relationship with Agent John Connolly (Joel Edgarton), whose roots in South Boston prove instrumental in getting Whitey to cooperate with the feds. Despite his efficacy in providing information on the Angiulo Brothers crime syndicate (eventually leading to their arrest), Bulger has more than a little difficult adhering to the condition that he himself not participate in any criminal activity while working with the Bureau. This is all further complicated by the failing health of Bulger’s son, the stress from which makes him increasingly unstable. On the other side of the equation, Connolly’s relationship with Bulger’s Winter Hill Gang becomes unprofessionally chummy, and Connolly’s loyalty to Bulger in particular calls the whole of the operation into question.

Much like in other Boston crime films, “Black Mass’”s vision of the city is stark, almost wretched. Boston appears on screen as a collection of warehouses and abandoned lots, through which the Winter Hill Gang stalks with relative impunity. This is only heightened by Cooper’s intentionally washed-out palette, the calling card of all serious historical filmmaking. As the picture moves forward, the colors almost seem to dull, as though in cahoots with the film’s increasing lethargy. Still, looking around Cooper’s vision of Boston, one can’t help but feel like “Black Mass’” vision of Beantown is less inspired by the prestige gangster leanings of “The Departed,” and more by the pulpy grit of films like “The Warriors” and “Taxi Driver.” There as here, the central city is brought to life as something hungry and malevolent, a dangerous system knowingly concealing something cruel within it. The gangs of “The Warriors” also spend much of their time on the gleeful prowl, but that film has the sense to lean into the trashiness of its world. Even at midnight, the New York of “The Warriors” reads as bright and lively. Cooper’s Boston, on the other hand, feels like a depressive model, barren and deflated. Its sense of foreboding tugs the film towards something pulpier than it wants to be.

This ultimately seems to be the central problem at the heart of “Black Mass”: an old fashioned identity crisis. On the one hand, Cooper’s film rides the waves of a series of stellar performances towards something vaguely Oscar-baity. On the other, however, it revels in the shameless trappings of the crime thriller, content to hypnotize the audience with the seething energy of Depp’s Bulger. Ultimately, the central conceit of the picture reads something like a cautionary horror film: society, when faced with something vastly evil, is arrogantly convinced that they can harness it. Spoiler alert: They can’t. It’s a tried and true premise, a gripping and dependable one. Unfortunately for Cooper, it’s not an inherently prestigious one, and decorating the film with all sorts of dignified trappings does little to obscure this. It’s the exact same problem that sank Cooper’s “Out of the Furnace,” an Appalachian gangster picture that mistook itself for a treatise on family, and threatens to undermine the most gripping elements of “Black Mass.”

Those would, of course, be the performances, which make up the majority of reasons for paying the ticket price for “Black Mass.” For weeks, critics have been talking about the film as the resurgence of Johnny Depp as an effective character actor, and he is indeed gripping. Still, the most interesting performance of the film belongs not to Depp, but Edgarton as Connolly. Like Mark Ruffalo in last year’s “Foxcatcher” (another piece of potentially clever pulp sunk by its own self-regard), Edgarton has turned in a performance that manages to be both endlessly understated and physically dynamic. Much of Edgarton’s work seems to happen below the neck, in the way he carries himself in the office versus the way he carries himself around Bulger. When the camera’s emphasis does shift to his face, the actor offers a portrait of something like a gradually eroding stoicism. Much of the thrill of Cooper’s film, in fact, comes from watching for the moment when Connolly realizes exactly how badly he’s screwed up.

Depp, on the other hand, conducts himself with such lush, decadent menace and scenery-chewing glee that he all but forces himself to be the center of every scene. His Bulger seems to be an amalgam of much of his previous work, combining the outsize madness that became his bread and butter under late-stage Tim Burton with the more reserved affectations on display in films such as “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape.” Still, Whitey here is the sort of villain you might find in a “Lethal Weapon” picture, composed of such unabashed evil that it’s hard to imagine why anyone would be doing anything with or near him. In his makeup and contacts, Depp looks like a reanimated corpse, spectral and almost diseased. As the film progresses you can watch the light leaving Bulger’s eyes.

It seems, though, that Cooper’s film doesn’t always know how to handle the character that sits at its core. In heightening Whitey’s macabre appearance, you can feel “Black Mass” announcing that it wants nothing to do with humanizing this man. Still, in scenes where Bulger frets over the condition of his son, you can feel the picture considering if it might be worth reneging on that decree. Really, “Black Mass” has very little idea of how to tackle the local legacy of its main character, who was seen both as an unspeakable monster and boogeyman and as something of a folk legend, a twisted sort of mascot for the city. Most often, “Black Mass” opts to go the monster route, though in certain moments of violence you can feel it straining to not play up the excitement just a little bit. Some might argue that this thematic conflict is mighty fitting, given that it reflects the complicated legacy Bulger himself left in Boston. Unfortunately, that sense of contradiction feels accidental and not considered. In the end it makes Cooper’s film a somewhat limp package for this story to come in, handsome as it may be.

Comments are closed