Female sexuality is represented in countless ways in the media, from the now infamous New York Times article that detailed the new “hook-up” culture and how it’s driven by college-age women to Miley Cyrus’s questionable argument that her raunchy performances are empowering and feminist. (An honorable mention goes to “Masters of Sex,” which provides a more candid yet still somewhat manipulated interpretation of the topic.) Yet possibly the most honest and accurate way I’ve ever seen it represented is in “Diary of a Teenage Girl,” which depicts 15-year-old Minnie Goetze (played by newcomer Bel Powley) and her exploration of sex and identity in 1976 San Francisco.

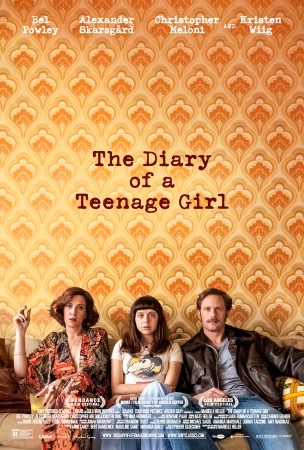

Beyond Powley, the cast of “Diary” is stacked. Alexander Skarsgård perfectly balances grimy and alluring in his role as the subject of both Minnie and her mother’s affections. The cast also includes Kristen Wiig in the role of Minnie’s mother, Charlotte, as a caricature of the classic ’70s parent, as well as Christopher Meloni as Minnie’s humorously intellectual, yet still somewhat endearing, former stepfather.

Most reviews of “Diary” present its basic premise as a young girl who begins an affair with her mother’s boyfriend. But Minnie’s storyline soon reaches beyond this relationship and becomes a journey of experimentation: she briefly pursues boys her own age (who, to her disappointment, are not quite as skilled as her older lover); ventures into light prostitution on a night out with her friend; dates a manipulative girl with a heroine habit; and experiments with various other drugs (a practice that’s reflected in her own mother’s pastimes as well). We see the ways she interprets each of these exploits: some, she thoroughly enjoys; some she regrets; on some, she is ambivalent. You might say the film is an exploration of exploration itself.

While 23-year-old Powley has the luck of appearing about 10 years younger than she is, it’s more a testament to her astounding skill that she can so perfectly emulate a girl on the brink of adolescence. Her cherubic face and deep-set wide eyes join an innocently matter-of-fact tone and child-like candidness in this startlingly realistic portrayal of a 15-year-old. An especially accurate quality of girls this age that Powley expresses to a tee is Minnie’s thirst for knowledge and simultaneous air of superiority when discussing knowledge she has recently gained.

Despite the bizarre and vaguely disturbing premise of a 15-year-old’s affair with her mother’s boyfriend, the movie is universally relatable. It addresses sex, growth, maturity, mother-daughter relationships, and experimentation in ways that span time and class. It examines the way we deal with trauma and anger in the explosion between Minnie and her mother at the inevitable discovery of the affair. Most importantly, though, it chronicles a young girl discovering her sexuality. Minnie enjoys sex, and the movie frames this enthusiasm in a positive and understandable light, instead of condemning her as a sex-crazed lunatic.

It’s also a sentimental look at the ’70s, from Minnie’s super-flare jeans to her use of cassette tapes to verbally record her thoughts and feelings. Her family dynamic (single, party-girl mother who moves from man to man and shares the experiences of her freewheeling life with her daughters) explores concepts of family, child-rearing, and feminism in this era, which is, put mildly, a liberal time in history. The whimsical elements of the movie also create this ’70s feel: Minnie’s drawings periodically self-animate and begin crawling across the screen, in distorted, trippy shapes and forms. The moving doodles, Minnie’s aspiration to be a cartoonist, and her fan mail correspondence with her favorite graphic novelist all act as tributes to the film’s origin, a graphic novel by Phoebe Glockner.

“Diary of a Teenage Girl” explores adulthood and childhood by placing its protagonist smack in the middle of the two. She brings a wide-eyed innocence from her past, but as she gains knowledge and experience, she begins to take on a new maturity, facing adults head-on and questioning their authority and moral superiority. The adults in this film are just as childish as Minnie herself, and this completely erases the line we like to draw so definitively between young and old, experience and lack thereof.

“Diary” is also refreshing in its portrayal of youth, painting Minnie’s recklessness in an almost neutral light. It doesn’t quite praise her sometimes-perilous exploits, like much entertainment aimed at a young audience does, but it doesn’t condemn it, either–it’s not a warning about engaging in risky behavior. It approaches her stunts with a neutral angle, looking at them for what they are: attempts to define one’s identity at an age where identity is everything. It also explores the way that these impulses mirror the ones upon which the adults around her act, again reminding us of the blurred lines between childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. And finally, the film uses these exploits to avoid becoming too heavy-handed. They provide humor, fun, and vibrancy to a storyline that has the potential for becoming far too sinister.

It’s a relief to finally see an honest and open approach to topics such as adolescence or female sexuality, which are constantly over-inflated, distorted, and generally mistreated in most forms of mass entertainment. Its directorial and actorial feats aside, it claims a cultural significance and necessity in providing a non-judgmental account of Minnie’s life—an account that, not unimportantly, remains thoroughly enjoyable.

Leave a Reply