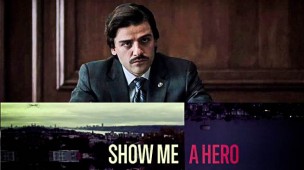

David Simon's “Show Me a Hero” is a blistering, low-key examination of politics and change.

David Simon, creator of HBO’s “The Wire” and “Treme, ” does not pander. Famous for his curmudgeonly attitude, Simon seems to delight in creating television that appeals only to a select few, willing to invest themselves unquestioningly in whatever topic Simon is interested in at the time. If his work wasn’t so engaging, it might be tempting to call the showrunner elitist or exclusionary (not that these are charges to which Simon would take offense). In fact, part of what makes David Simon’s work so enthralling is the trust it puts in its viewers. Rather than holding audiences by the hand and leading them through Simon’s increasingly baroque storytelling, programs like “The Wire” dedicate themselves not to entertainment value or recap-ability but to narrative honesty, unflinching fidelity to theme and character, and a willingness to leave casual viewers behind in favor of frustratingly realistic nuance.

“Show Me a Hero,” Simon’s latest series, which aired this summer in six parts over three consecutive weeks, is no different. Telling the story of Yonkers mayor Nick Wasicsko and his fight to install a set number of federally mandated public housing projects in the city, “Hero” delights not in moments of grand drama but in the slow build of procedural debate and the gradually crumbling façade of white middle class decency. Like films such as “Lincoln” and “Selma,” Simon’s latest concerns itself with the legislative skeleton of change, the practical process of social evolution, but unlike its fellows it seems almost allergic to sweeping gestures. Instead, it accrues a collection of small moments and demands that audiences do the work of assembling these moments into a tapestry of greater thematic import. With the eye of a journalist and a historian, Simon crafts a narrative that defies traditional television structure in favor of something less instantly rewarding, but ultimately more fulfilling. It’s large-scale drama transposed onto a small municipal scale, stripped of fat and pretense. Imagine if CSPAN was suddenly directed by Sidney Lumet.

Playing Wasicsko, Oscar Isaac once again asserts himself as one of today’s best working actors. Much like his performance in last year’s criminally underseen “A Most Violent Year,” Isaac’s work in “Hero” is perfectly understated, full of boiling stress and strain that never amounts merely to some cheap onscreen blow-up. Isaac’s Wasicsko might be described as idealistic and in over his head, but neither Isaac nor the script allow this combination to move into the territory of cliché. Wasicsko is, instead, wry and weary, worn down by a world not that he is too smart for but of which he is a part. As roadblock after roadblock appears in his path, Wasicsko broods because of the inevitability of these difficulties. In the first third of the series, Isaac’s transition from elation to frustration over his new role of mayor is played perfectly: a natural progression that his performance telegraphs through small well-placed gestures and keenly calibrated line-readings as opposed to via effusive soliloquy.

The series is strengthened by a bench of stellar supporting performances by the likes of Alfred Molina, Winona Ryder, Jon Bernthal, and even Jim Belushi. As Wasicsko’s main opposition, Hank Spallone, Molina embodies the boisterous, grating populism that one might normally expect from the protagonist of a program such as “Hero.” Spallone’s anti-integration grandstanding is the most heightened rhetoric on display, and its combination with his snide manipulative attitude in backroom meetings exposes the inherent dishonesty of a certain strain of political drama. Still, “Hero” never casts any of its characters as outright villains, even as they antagonize and undermine each other with mounting verve. Alternatively, Simon depicts a group of legislators fighting for their own, increasingly certain that they have the moral high ground, that there is room for moral high ground in the swamps of legislative pragmatism. Playing an NAACP lawyer, Bernthal is as obvious a moral crusader as “Hero” is willing to offer its audience, and even he is, by turns, arrogant, short sighted, and ill tempered.

The result is a program that is willing to take its time, to dig into the procedural details of its subject and to almost gleefully sidestep the sort of climaxes that audiences have come to expect from courtroom dramas and their political siblings. In this way, “Hero” is a great deal like Simon’s previous HBO miniseries “Generation Kill,” which depicted the early days of the United States invasion of Iraq from the perspective of the first troops on the ground. Both programs passionately explored the tediousness of their subjects with a sort of nerdy elation, taking more time to talk about the ins and outs of process than to race forward through a series of money shots. In fact, when either miniseries did find the time to create a moment of high drama, their respective scripts seem far more interested in the lead up and the fallout, diagramming the moment as part of a larger narrative and historical continuum as opposed to the big scene that the writers expect to be the obsession of bloggers and recappers in the wake of the credits.

If there is a weak beam in the structure of “Show Me a Hero,” it is Paul Haggis’ direction, which often feels ill-suited to the pacing of Simon’s writing and the performances of the actors. Much like in his 2005 Oscar-winner “Crash,” Haggis is all too hungry for moments of “importance,” and even more willing to instructively spell them out with his camera. Since no moments in the script necessarily call for the sort of didactic heavy-handed filmmaking that made “Crash” so digestible and forgettable, Haggis seems to be trying to create such moments out of thin air. He digs around the sets and ensemble for scenes that force the audience to perk up in a way that can feel almost campy at worst. Unfortunately for Haggis, Simon has no interest in creating the sort of swelling director’s showcase that the camera seems desperately trying to manufacture, and so very often the filmmaker’s stylistic showboating appears reasonably amateurish. Where Simon wants to trust audiences to engage themselves and following along, Haggis wants to grab viewers by the throat and announce the material as important. Luckily, there seem to be long stretches where Haggis has either gotten the message or simply tuckered himself out. “Show Me a Hero” is at its best when the director lets the material breathe and bloom on its own, when he lets the stakes amass as they do in reality. That the ending of “Show Me a Hero” is antithetical to the sort of broad-stroke teachability that Haggis specializes in might have finally helped the filmmaker get the message.

Before “Hero” premiered, Simon did a number of interviews in which he seemed to delight in predicting how few people would actually care about his newest series. Perhaps annoyed by the popular acclaim bestowed on “The Wire” only after it was finished (combined with the lack of attention paid to the equally impressive “Treme” and “Generation Kill”), the showrunner cast his latest as something diametrically opposed to the current television climate, where prestige television is still shot through by a certain amount of dramatic adrenaline. It would be nice if Simon were, this once, proved wrong because “Show Me a Hero” is truly a thing of beauty and despite its low-profile style, importance. It would be all too easy to harp on how well the miniseries reflects current rhetoric around race and government responsibility and to leave it at that, but, ultimately, Simon’s primary goal does not seem to be to make a point. Rather, like in his previous work, the poster boy grouch of modern television is here to tell a story, craft a world, and explore the consequences of the choices made therein. That we see ourselves reflected in the resultant work is simply a byproduct of Simon’s commitment to complex, unerring honesty. It’s a blessing in disguise that he refuses to make things easy.

Comments are closed