It’s easy, in the world of Buzzfeed, the Huffington Post, and Cracked, to take music lists for granted. Talking about albums and songs, it’s easy to resort to rankings: the best of the year, top five break-up songs, biggest disappointments. Perhaps that takes some of the thrill out of watching “High Fidelity”—Stephen Frears’ adaptation of Nick Hornby’s novel, which turns fifteen at the end of the month. Still, there is no film that I can think of that better understands both music and the way we build our lives around taste.

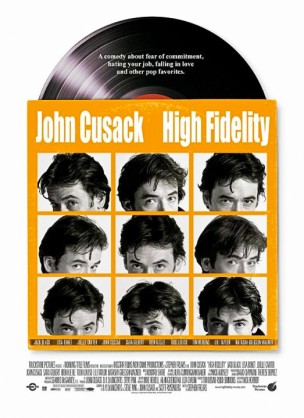

“High Fidelity” has a simple enough plot. Rob Gordon (a pitch-perfect John Cusack) has just been dumped by his girlfriend Laura. She claims he has no aspirations or momentum, that he is insensitive and testy. None of this is untrue. Rob works as the proprietor of a small independent record store where he and his two employees (Todd Louiso and Jack Black) spend all day compiling rankings of albums: the world condensed into top fives. A depressed Rob decides to rank his top five break-ups and, eventually, to contact each one of his exes on a quest to figure out what went wrong. Spurred by a brief cameo by Bruce Springsteen, he pushes onward, hoping to find a way to correct his course and make amends.

In lesser hands, “High Fidelity” could have been a disaster. The film demands such a careful combination of acid and warmth that Frears seems to have calculated painstakingly. Too much bite and the film becomes a cynical, musically-inclined bludgeon. Too much cloying sentimentality and Rob ends up looking like a self-pitying “nice guy” jackass, whiny and insensitive. Mixed correctly, though, the two intertwining tones paint a funny and unsparing portrait of the ways we use art to comfort and trick ourselves, and the bridges that music can both build and burn. On rewatches, it’s easy to think of the Animal Collective song “Taste,” but Nick Hornby got there first. “It’s what you like, not what you’re like,” Cusack explains with self-satisfied relish.

Of course, Rob is proven wrong. Despite having a brief affair with a singer talented enough to make “Peter fucking Frampton” appealing, he finds himself drawn back to the qualities of his exes that exist outside of the rankable world. Not everything he remembers proves to be as positive or comforting as he remembers it, but there’s a level of closure and wisdom that comes with confronting the mess. In the end, Rob has to confront some of his own truly ugly qualities, and the film has the decency not to mitigate them, even as Rob desperately tries to.

Other films have tried to capture the redemptive romantic arc, but few have done so as well as “High Fidelity.” Sure, Seth Rogen can flush his stash and build a crib in order to win the affections of Katherine Heigl, but there’s something deflective in that. For Frears and Hornby, the real truth is buried not in the fact that we make mistakes, but in that those mistakes do real tangible damage. It’s easy to romanticize the pain we feel and the pain we make others feel, but a song that lasts a mere three minutes can only inform, never fix.

“People worry about kids playing with guns, or watching violent videos, that some sort of culture of violence will take them over,” Cusack mopes early on. “Nobody worries about kids listening to thousands, literally thousands of songs about heartbreak, rejection, pain, misery and loss.”

This might all be exceptionally mean-spirited if it wasn’t for the shameless love that both Hornby’s book and Frears’ film have for the music they reference. Scenes set in Rob’s store hold on conversations about Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat or Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You.” There are scenes soundtracked by the Beta Band, Belle & Sebastian, and 13th Story Elevators. The film ends with a simultaneously goofy and stirring cover of “Let’s Get it On,” as performed by Jack Black and his band Sonic Death Monkey (or Barry Jive and the Uptown Five).

In the wake of “High Fidelity” it’s interesting to see the growth of the listicle. Perhaps it speaks to what the film is trying to pin down—the ways we compartmentalize and equivocate and simply complicate relationships and artifacts—or maybe it’s just a journalistic development like any other. Still, when I next sit down to watch Frears’ new classic, I wonder how I’ll absorb it. What moments will leap out? What songs will grab hold? Where on my list of favorite films will “High Fidelity” fall?

Comments are closed