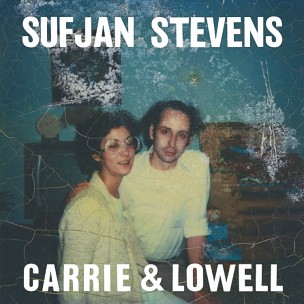

c/o wikipedia.org

Carrie & Lowell, the seventh studio album from Sufjan Stevens, begins with an invocation. “Spirit of my silence, I can hear you/but I’m afraid to be near you,” Stevens sings over the lilting chords of his guitar. “And I don’t know where to begin.” That opening track “Death with Dignity” sets the stage for much of what’s to come. It moves gracefully forward, somehow both spare and lush. There’s a warmth and a fierceness beneath the music, a grateful intake of breath and a gritting of teeth. It’s “Sing in me, O Muse” as the picking of a scab, perhaps less invocation than incision.

After that first cut, Carrie & Lowell rushes out unallayed. It’s a record of profound beauty and desperate agony, that somehow dwarfs even Stevens’ more overtly grand efforts despite its own bare essentials approach. When it was first announced that Stevens’ would be returning to his folk roots, many a mind leapt to Seven Swans, the singer-songwriter’s stripped-down fourth LP. But even Swans feels sonically massive compared to Carrie & Lowell. Whereas many of Sufjan’s previous albums have engaged in myth-making—combining Biblical and local iconographies to create monuments to their subjects—Carrie & Lowell seems interested in the exact opposite. If Seven Swans, Illinois, and Michigan create community and comfort in the interweaving of multiple narratives and experiences from across time and geography, Carrie & Lowell fixates on its isolation. The album tells a single story and that story traps its creator. More so than trying to transcend, historicize, or escape tragedy, Carrie & Lowell captures the efforts of one individual attempting to live with and in his pain, unimaginable as it may be.

The wound that Carrie & Lowell investigates is a deep one. As recounted by Stevens in a fantastic recent interview with Pitchfork, the title of his new record refers to his mother, who left Sufjan and his father when he was one year old, and the man who she lived with for much of her son’s childhood. Carrie, who passed away from stomach cancer in 2012, suffered from schizophrenia, bipolar depression, and a number of addictions. Much of her decision to leave, Stevens explains, came from her anxieties about how her struggles would impact her son. When Stevens was five she married Lowell in Eugene, Ore. As Stevens’ explains, he spent three summers with the couple before their eventual split.

This is a tortured history, littered with a multitude of moments and subjects that could, on their own, sustain an entire album. As such, it is especially impressive that Stevens has managed to discuss them all on Carrie & Lowell, without shying away from their complexity and ugliness. He never deflects of equivocates. He never shies from or discards any of this pain. Rather, he catalogues it and sets it in its place. One might call the record an exorcism, but it is one where the demon stays in the room to converse with his host afterwards. The locating of the pain, coaxing it out, is only the first step of the process.

The rest of the album, then, is that conversation: a recounting of memories, anxieties, and questions. At times, Stevens references specific moments in his life—he mentions being left at the video store by his mother in “Should Have Known Better,” and the fifth track, “Eugene,” explicitly refers to his time in Oregon—but, for the most part, his approach is deeply impressionistic. As on previous records, Stevens locates a great deal of his emotions in religious imagery, but here those allusions feel less confident, less hopeful. On songs like “Drawn to the Blood” these nuggets of mythology feel like false promises, generous and dishonest. They are unstable, inconsistent, and, perhaps, not punishing enough for what Stevens feels.

When they do hold true (“Jesus I need you, be near, come shield me/From fossils that fall on my head”) they are often end up perverted or mutated. On “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross,” the symbol of the crucifix dissolves into a haze of tortured conflicting imagery, combining the fantastical and the mundane: “Like a champion/Get drunk to get laid,” Stevens sings, and only a few lines later claiming, “I’ll drive that stake through the center of my heart/Lonely vampire/Inhaling its fire.” A far cry from Stevens’ earlier works such as the haunting “And All the Trees of the Field Shall Clap Their Hands,” this is a religion of doubt, martyrdom reconfigured as self-mutilation. If there is any moment of scripture “No Shade” seems to recall, it might be Christ’s moment of despair on the cross: “God, my God; Why have you forsaken me?”

Moments like this create a sense of constant, confused distress as the cocktail of mourning drags Sufjan through various shades of a baffling and evolving sorrow. Flashes of comfort are short-lived, and often followed by an even deeper pain. Fourth of July fireworks are punctuated by pet names and then ruptured with affirmations of death. Fever and fire ravage the world, while Stevens gestures to something between peace and assent: “Oh could I be the sky on the Fourth of July?” In many ways, the track’s gently whispered mixture of wonder and terror recalls Stevens’ “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.,” another song that woefully twisted the trappings of the American summer lexicon. Here, too, there is an almost awestruck self-hatred, a disgusted marveling at the depths of one’s inability to be or to respond as they should. Sufjan does not have the naked corpses of murdered boys stashed beneath his floor, but the odors and energies of death diffuse through his home nonetheless.

Carrie & Lowell is not a long album—it clocks in at roughly 43 minutes—but it is an exhausting one. There is no filler, so there is no checking out, and while we’re never quite invited into the moment with Stevens, the emotions on display still hold us in their sway, spreading from body to body, track to track. As opposed to other records that might make a point of closure or compassion, Carrie & Lowell seems interested in the spaces that those forces leave unfilled. In many ways, it is an album of questions, reaching out into the indifferent quiet of death.

There is warmth and forgiveness, but there is also profound sadness that exists without antidote. On “The Only Thing,” Sufjan considers suicide, piling question upon question in the process: “Do I care if I survive this?/Bury the dead where they’re found/In a veil of great surprises/I wonder, did you love me at all?” As the song progresses, his inquiries become more and more fitful (“Should I tear my eyes out now, before I see too much?”) but all orbit around one lingering question: “How do I live with your ghost?” Again and again, Stevens calls out for an answer, but all he can reach is a sort of slant-rhyme response. “Everything I see returns to you somehow,” he whimpers. Perhaps that is the only answer available. It is maddening, and painful, and cyclical, defying expectations and demands of satisfaction. But it’s the only thing that feels true.

Comments are closed