The Viet Cong’s self-titled album opens with peals of thunder, the rumbling mounting echo of kettle drums dragging the listener into the heart of the storm. For a debut LP there is no shyness here, only a concentrated, fearless demonstration of skill, coursing rays of static and distortion, crackling chants, and rising tongues of melody. Despite having formed back in 2012, Viet Cong determinedly announces itself, boisterous and awe-inspiring. For a band whose style can so easily be connected to the giants of the post-punk movement, the Calgary-based quartet feels entirely new.

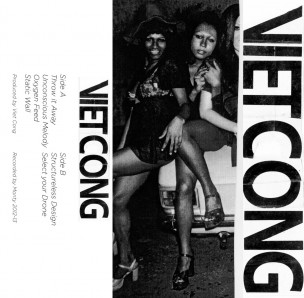

It may seem odd that a band formed in 2012 would wait nearly three years to release its debut, but that would ignore the consistent work Viet Cong has done over the past few years. In 2013, the foursome released its seven-track EP Cassette, which, on its own, boasted an armada of wonderfully rendered, layered cuts. Then as now, vocalist/bassist Matt Flegel, drummer Mike Wallace (both formerly of Canadian band Women), and guitarists Scott Munro and Daniel Christiansen honed in on a single textured sound and allowed their music to grow in all directions from there. The group has been rightly compared to the likes of Joy Division and New Order, but to stop there neglects to mention the sheer diversity of its output. Viet Cong is by turns aggressive and tender. The group is empathetic, witty, and biting. Beneath the layers of reverb shimmer the chords of acoustic guitars and the shifting rhythm of a wide range of percussion. Synthesizers speckle and blink atop razored currents of throbbing bass lines. There is no one way to describe their music.

As an outfit, Viet Cong rewards close reading. As much as they distinguish themselves from their forebears, the ways in which the four members play with the musical legacy of bands like Joy Division and New Order, of Siouxsie and the Banshees and the Cocteau Twins, and of more recent bands like The Walkmen and Women, adds unforeseen weight and texture to both their releases. On Cassette, tracks such as “Structureless Design” pulse beneath shadows of distortion, marching along on the sort of lyrics that would make Ian Curtis proud. The whole song seems haunted, as though something terrible swims just beneath the folds of guitar and bass. But rather than simply maintain that suggestion for four minutes, the track expands, closing with a minute of furious punk thrashing and howling that seems to reach out above the haze that coats the opening three minutes. On the EP’s next cut, “Dark Entries,” those guitars push forward even further, closing in on the sort of gleeful war chant that might sweep forth from a Stooges song. Viet Cong knows when to hold back and when to cut loose. The band’s members are adepts of the slow build and acolytes of that sudden fracture when a song splits open, releasing all of the energies that were accumulating within it.

This is true, too, of their new record, which is both less reserved than Cassette and also far more attuned to the pitch and direction of their music. Tracks like “Bunker Buster” shift effortlessly between tones and tempos, building and then depleting themselves before building once more. Each cut off the album feels like a distinct animal: living, breathing, circling something vivid and unpredictable. “You tell me where you came from,” Flegel sings as “Bunker Buster” descends, portions of the instrumental slowly shutting themselves off before exploding to life once more. It’s wonderful and highly controlled, but also wholly unpredictable. There’s nothing to say when the track will finally end, nothing to suggest that the band couldn’t go on like this forever, living perpetually within its shuddering sound, moment by moment discovering new chambers to explore.

Even more straightforward tracks such as “Continental Shelf” find ways to contort and transform themselves. Insistent drums give way to gentle guitar lines, which are devoured by militant waves of static. “The skyline folding in/Nothing is beginning/Edges falling off themselves/And the water is draining/Off the continental shelf,” intones Flegel. Somehow, the track manages to be both in mourning and resistant, dancing effortlessly back and forth between a battle cry and a eulogy. In just over three minutes, the whole of this album’s world can shrink down to the size of a single note then blow up once more in the space of a moment.

In many ways, this holds true for the whole record, which clocks in at about 36 minutes. It’s lean and rigorous, but somehow grand and immutable. The closer, “Death,” clocks in at over 11 minutes on its own, but it never feels bloated or self-indulgent. Even with such a dour, perfunctory title, the song demonstrates a greater degree of life than far less morose counterparts. On a different album, this would be a slog of a destination: sluggish, inert, intricate but empty. Instead, every minute of “Death” promises to start the record all over again, pushing forward unselfconsciously to erupt in a finale of furious drumming.

It seems almost impossible, even after having listened to Viet Cong on repeat for nearly a week, to try to sum up what makes the whole excursion so powerful. Perhaps it’s the songwriting, which folds upon itself in strange and wonderful ways, both prayerful and hopeless in turn. Maybe it’s the orchestration, which both overwhelms and invites, at times impenetrable and at others uncommonly welcoming. Perhaps it’s the way in which the whole record seems so willing to adapt and grow, songs sprouting out of one another, lyrics dancing on the shoulders of one another. Perhaps it’s simply that, more so than many albums, Viet Cong feels undeniably alive, even as it buries and exhumes itself track by track. It’s a beautiful thing to see this much joie de vivre in a death wish.

Leave a Reply