With the Academy Awards rolling around, The Argus Arts section took look at the nominees and made our own predictions. We asked who might win, which underdogs we are holding out for, and which of the absent films should have snuck into the Academy’s bracket. In the process, we examined the ways in which categories are organized, judged, and evaluated, and revisited those films that have moved us over the course of 2014.

Best Picture • Screenwriting • Director • Acting • Foreign Feature • Animated Picture

It’s often hard to fully capture the influence of the director on a film. For some, theory dictates that a movie is wholly the product of directorial will—the unabashed creation of one individual, crafted and contoured by a single, unflinching vision. For others, the film is a product of collaboration, corralled by a vision that must adapt to the texture of performances, writing, and an evolving product. Neither of these is correct or incorrect. Both provide worthwhile insight into the ways in which a director can succeed or fail.

The Oscars, then, serve as a way to measure and reward these successes and failures, and provide spectators with an interesting slate of directorial achievement. It also provides a chance to discuss questions of responsibility in filmmaking. Do we hold directors accountable for the aspects of films we find invigorating or repulsive? Do the ethical deficiencies or artistic discomforts that we sense on screen have their roots in the filmmaker? How can we recognize technical achievement and aesthetic power simultaneously and separately?

These questions are especially relevant this year in the wake of the snub of Ava DuVernay, the director of “Selma.” Many argued that the political closeness and racial boldness of “Selma” put off Academy voters who felt that their recognition of “12 Years a Slave” in 2014 exempted them from some sort of imagined political nomination of DuVernay. Others anonymously claimed that DuVernay’s film seemed to use its political relevance to coerce a nomination from the Academy. This is, of course, absurd, but it also gets at those questions of voice. Do the elements of “Selma” that make Academy members uncomfortable override the immense technical ability, aesthetic mastery, and emotional power of the film? Is the director responsible for the political reactions of the viewer? In my mind, no. “Selma” is one of the best films of the year, and much of this stems from DuVernay’s touch, vision, and control. As an example of a director’s influence, “Selma” is masterful and DuVernay (whether or not she would or should win) deserved the nomination over some of the others now enjoying their own.

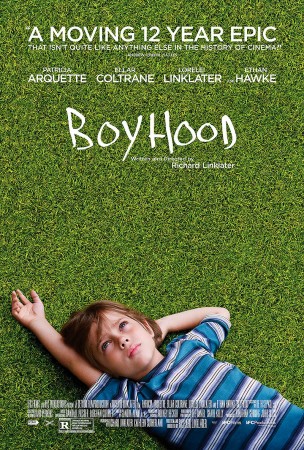

But of the selected five, what can we say? Well, most likely, the win will go to Richard Linklater, who directed “Boyhood.” And it should. As an example of directing, “Boyhood” is unparalleled, a feat of shaping and reshaping a vision for over a decade in service of a single story that sprawls outward in all directions. For 12 years, Linklater worked with his actors, shelving and unearthing narrative devices in order to be honest to their development. As an artistic work, the results are magnificent. As a window into the organizational and logistical responsibilities of the director, “Boyhood” has no peer.

This is not to diminish the accomplishments of the other nominees. With “Birdman,” Alejandro González Iñárritu crafted a rhythmic and effortless character study, blending the magical absurd and the crushingly human. It feels effortless and dynamic, yet teeming with intent and consideration. In “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” Wes Anderson (nominated for the first time) created an intricate political and emotional world teeming with visual splendor. He blends whimsy and darkness in ways that—though not always effective—bring the picture to life with a wondrous physicality. The vantages of textures of his sets are explored by his deft camera and loping characters. Bodies move through spaces that both overwhelm and inform them. Even as the film dips into political abstruseness, the candied melancholy of the world compels a response from the viewer. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Bennett Miller of “Foxcatcher” produced a film of rigorous journalistic sparseness, a stripped-down vision of the largest and smallest questions present in a thriving America. For some, the film’s refusal to delve into the unsupported implications of its material represented a sort of artistic cowardice. For others, the bare-bones approach served as a sharp and integral choice to celebrate journalistic narrative in a medium that can often tend towards elision or unwise invention.

If there’s one director who I’m tempted to exclude from claims of greatness, it would be Morten Tyldum, whose “The Imitation Game” is aggressively safe in its structure, focus, and visual style. Whereas Miller’s harshly directed focus seems to heighten the procedure of story, Tyldum’s refusal to discuss the forces outside of his frame seems like an aversion to the necessary questions and darkness of Alan Turing’s life. There’s a competence and grace to the film, but no sense of scope or intention. The picture seems to get in and get out, leaving the viewer with a sense of prestige and prettiness, but no lasting impact.

Will Win: Richard Linklater, “Boyhood”

Should Win: Richard Linklater, “Boyhood”

Snubbed: Ava DuVernay, “Selma”