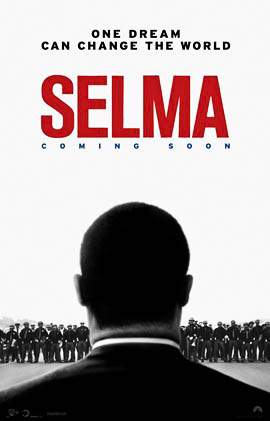

David Oyelowo assertively plays Martin Luther King, Jr. in Ava DuVernay’s biopic “Selma,” lingering in the details of a defining event in the Civil Rights Movement.

“Selma,” directed by Ava DuVernay, is a movie of textures: the thin cloth of blouses and rough wool of suits; the thick lattice of veins beneath cracked skin and the glimmering rivulets of blood and sweat; the cold classical imperiousness of marble, the grating patchwork of tarmac, the rust and the rivets adorning the stale metal of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. “Selma” is a small movie, but it is neither slight nor frail. It is packed with tenderness and cunning and anguish and humor and joy. It is brimming with passion and grandeur and scope, but never bluster. It is a biopic of silences and glances and moments. It is a history both unassuming and bold. It is daring and acute and necessary.

The film, which enjoyed a limited release on Christmas and moved nationwide on Jan. 9, is an excerpt of the American Civil Rights Movement that stretches warmly and sharply in all directions. Rather than attempt to encompass the magnitude of work done and undone, of questions unanswered and echoing, it lets the concerns of America’s racial legacy sprout from its surface, where they are carefully cultivated, discussed, and nurtured.

Beginning on Oct. 14, 1964 with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize, “Selma” charts King’s advocacy for voter rights for African Americans in the South and across the nation, specifically the Selma-to-Montgomery marches organized by King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the repeated violence surrounding their progression. Throughout its runtime, the film visits a host of characters from Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) in Washington, D. C. to Malcolm X (Nigel Thatch) on a brief visit to Alabama before his assassination. It moves fluidly from living rooms to lunch counters to highways to prison cells, like a road movie winding deliberately through the inner chambers and catacombs of a particular American spirit. It is brisk, but also takes its time in parts, lingering on carefully crafted moments of ecstasy, agony, and doubt.

King—played by David Oyelowo, a British-Nigerian actor—is the film’s centerpiece, but never its obsession. The picture asserts the archetypal civil rights leader as magnetic and imposing, but continually emphasizes the importance of those who worked alongside him, including Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo), who is depicted as a force to be reckoned with on her own terms: never jilted, or side-lined, or underestimated. At the same time, Oyelowo’s performance never tips into hagiography nor into the giant emptiness that normally stains the Hollywood biopic. In “Selma,” King is a man and an activist: hardworking, political, keen, and intuitive. He is haunted by doubt and guilt, and yet sustained by an undiluted faith in God. He rages and he cries, but he is always grounded: The rhythms of his speech charged with Oyelowo’s baritone resonate up from the stomach and the earth. (The King Estate would not give filmmakers the rights to King’s speeches, forcing them to craft a voice that feels both respectful and wholly new.)

Oyelowo gives a smart and understated performance that rises up out of itself and the film at crucial moments to touch on something greater, but never allows that unnameable something to overwhelm King’s physicality. Like last winter’s “12 Years a Slave,” “Selma” is a film of bodies from which all questions, motivations, and certainties of dignity inherently derive. DuVernay’s camera lingers on hands and faces, hair and muscle. It exults in the motion and tenor of these bodies, and mourns their violation furiously. King’s speeches are marked by the swing of his gestures and the shift of his weight. When, on the second attempted march to Montgomery, he kneels down in prayer before the cleared highway, it seems as though the eye of the film and the movements of his followers are tied to his physical gravity. There is nothing ephemeral here.

Perhaps that is “Selma’s” greatest triumph: its refusal to allow any of its history or themes to drift. Every moment of the film feels visceral, tangible, corporeal. DuVernay accents the inside of King’s home with warm pastels that turn sickly in the dark. The worn facades and thick red of brick make the streets of Selma heavy and distrustful. When a white minister from Boston is beaten to death by two white men for daring to participate in that second march, we are haunted by the depth of the night, the jagged motions across it, and the ugly neon glow of the diner sign which moments ago bathed him and his companion.

Never does the film attempt to sanitize its violence, though neither does it allow the unbearable brutalities to overwhelm its characters. Early in the film, DuVernay flashes back to four little girls descending the spiraling staircase of their church. They are framed in warm yellows and accentuated by the twinkling of sun-kissed stained glass. Moments later they are engulfed in an explosion, those previously benign tones hardening and sharpening, washed with reds and browns, fire and dust. Rather than cut away, DuVernay holds. From off camera, flame and debris are pumped into the frame, waves upon waves. Then, from beneath, we see a shoe, then a leg, the billowing of a dress. Across the screen scroll bodies; they glide upon the explosion like crafts on the ocean, peppered every so often with fragments of glass and wood.

This, of course, is the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, 1963. It is a signifier of the evils to come, the casual inflections of hatred and dehumanization that spark off the tips of night sticks and out of the barrels of police revolvers. It hangs in the corner of every scene, building and forcing the viewer to contemplate the state of fear that much of white America chose to uphold. Later in the film, when the first march from Selma erupts into violence, it feels like the fulfillment of a promise. Music swells as police proudly and tauntingly don gas masks and helmets, before charging out at fleeing marchers shrouded in thickening smoke. They grab men and women and hurl them to the pavement, batons rising like salutes from the darkness of the gas and then descending once more in slow motion. What we must see, we see. What we do not see, we hear: in screams, in thuds, in pitiless shivering cracks.

“Selma” does not turn away, and it rarely tries to neatly resolve. If the film’s conclusion, which winds around President Johnson’s announcement of his plans for the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to the completion of the third Selma-to-Montgomery march, somewhat resembles Hollywood in its neatness, it is counterbalanced by the unrelenting unease of the film’s journey. Certainly, the use of title cards to announce the fates of the film’s major players is mildly trite, but the inescapable sense of incompletion that has intensified over the last few months is not lost on DuVernay.

Even as King stands triumphant, the film announces itself as unfinished. It, of course, is in the business of telling an incomplete story and it has no illusions. That its “Where Are They Now” scrolls echo the memos of J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker) charting King’s activities, typed out on the screen at various points in the picture, seems quite intentional. There is surveillance in this history, and oppression even in its triumphs. With each of these successes, men like George Wallace (a breathtakingly slimy Tim Roth) expect the quest for equality to cease, and when it does not, they rage back horrendously.

For each forward step, for each achievement, there is a marking and a grumbling and a continued threat of violence. “Selma” understands this. It lives within that threat, and the history that that threat has carved into America’s landscapes. It does not have the answers on how to escape, but it has the compassion and humanity to announce that it will not settle for silence.

Comments are closed